Driving South from Ogden

I kept thinking about the meal I’d had the night before at Table 25 in Ogen, Utah. It lingered longer than I expected, the kind of dinner that stays with you into the next morning. I stopped at Starbucks early, and the staff were genuinely friendly in a way that felt unforced. Two employees were sitting at the tall table, so I took a seat by the window. Instead of calling my name, someone brought my coffee and bagel over and said, “I hope your coffee is perfect. Let me know if you need anything else.” It was small, but it landed just right.

It was just before eight, and I stayed there close to three hours—sending texts, answering emails, checking accounts, and trying to catch up on some writing. I mapped out a route south toward Moab, which came in at over seven hours. Lately I’d been leaning too heavily on interstates, using them to get places quickly, but missing the small towns and the everyday details you only see when you slow down. This felt like a good day to avoid them.

For some reason, I was surprised to see a Planet Fitness in Ogden. Utah has a lot more local businesses than I’d expected, and the national chains don’t dominate in quite the same way. A shower and a massage chair sounded like a perfect way to reset the morning. There was a large grocery store nearby, so I topped up there as well before getting back on the road.

By early afternoon, I was leaving Ogden. There were plenty of things I hadn’t seen—museums, neighborhoods, side streets—that would have to wait for another trip. Downtown had felt clean and relaxed, with seasonal lights still up, giving the place a slightly festive edge even in daylight.

My non-interstate route climbed up through the pass behind town, winding back and forth through the canyon. After only a few miles, traffic thinned more than I expected. The canyon opened up and quieted down quickly, and even though I wasn’t far from the city, it already felt removed.

Pineview Reservoir sits northeast of Ogden, tucked into Ogden Valley. The dam stands in a narrow gap between the mountains, a natural choke point that makes its purpose obvious. Built in the 1930s as part of a New Deal project, it was designed to control flooding on the Ogden River and store water for agriculture and growing communities downstream. Holding the river back here creates a massive lake that stretches across the valley, far larger than it first appears from the road.

I stopped at the top of the dam to grab a few photos, which isn’t easy. The road is narrow, and there’s really only one safe pull-off if you don’t want to feel rushed. The view is good but partially blocked by barriers meant to keep people moving. You can see enough to understand the scale—water spreading out into the distance, mountains wrapping around it—but not quite enough to linger comfortably. It feels like a place designed to be passed through rather than explored.

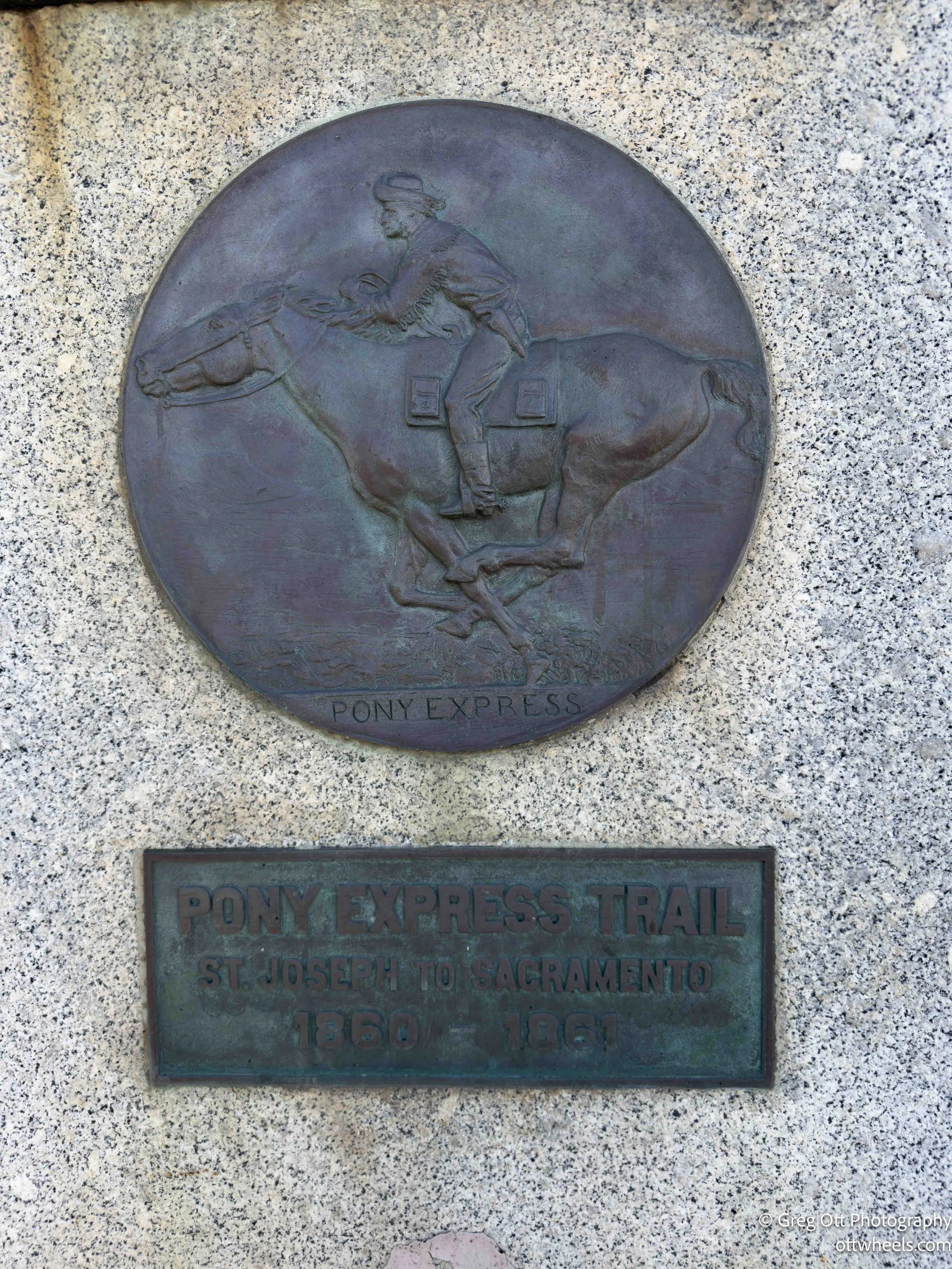

I passed through Henefer, easy to miss and barely registering as a destination. Along the roadside, a plaque noted that Brigham Young passed through here on his way to the Salt Lake Valley. Just below it was another marker describing the Pony Express route that followed the same corridor.

Standing there, it was clear why both came through this way. The land narrows and opens at just the right points, a natural path through the hills. Today it’s quiet, almost unremarkable, but for a moment it felt like one of those thin places where history didn’t stop—it just passed through and kept going.

I stopped again at Rockport Reservoir, where the Weber River widens and calms. The reflections were immediate and striking. The water was still enough to mirror the mountains almost perfectly, the ridgeline behind me doubled across the surface. It felt briefly symmetrical, as if the landscape had paused long enough to take its own picture.

There’s a well-kept DNR pull-off here with restrooms and a large parking lot that was nearly empty. It’s clearly built for busy weekends, but on this day it was quiet and open. I took a long break, made lunch, and sat with the view longer than I expected. Every small change—light shifting, a ripple moving through—reworked the reflection without breaking it.

The road behind me was calm as well. Very little truck traffic, just the occasional car moving through the valley. The hills rise cleanly from the water, and with the reflections in place, the space felt larger than it actually was. It was a genuinely relaxing stop, the kind that gives back more than you planned on.

I continued on toward Coalville and stopped briefly to photograph the Summit County Courthouse. The building stands out immediately—solid, symmetrical, and clearly meant to be noticed. It has the kind of presence that anchors a town, even if you’re only passing through.

I didn’t spend much time there. I was watching the light and still trying to make it to Deer Valley before dark. From what I could see, Coalville felt calm and well-established, shaped by its role as a county seat rather than a tourist stop. It was a pause, not a visit.

I had planned to spend the next day skiing Deer Valley Resort, so I approached Park City from the north, coming in through the Empire Pass side. I wasn’t prepared for the scale of it. What unfolded felt less like a town and more like a massive condo village stacked into the hillsides. Building after building, all variations on the same theme, flowed uphill with no clear edge.

From that direction, Park City never really announces itself. There’s no moment of arrival, no obvious center. It feels designed to be entered rather than wandered, impressive in its own way but slightly disorienting.

I eventually passed Deer Valley itself and started questioning how much skiing there really was to be had. The resort was advertising around twenty percent of the terrain open, but that felt generous. They hadn’t had snow in weeks, and parts of the mountain were bare enough that it was hard to imagine it skiing well. The contrast was striking—so much infrastructure built around very limited conditions.

As I kept driving, another realization set in. I still had no idea where I was going to park for the night. It was immediately clear that it wasn’t going to be in Park City. Between the density, the visibility, and the feeling of being very much in someone else’s space, nothing about it felt compatible with quietly disappearing for the evening.

By the time the sun had set, I pulled over just after the stretch I’d started calling condoville, down in Jordanelle State Park. I could see campground loops below the road and a few trailers already tucked in, which gave me a brief sense of hope. That faded quickly. Signs at the entrance said the area was closed for the winter, and equipment was staged for off-season repairs.

I drove down toward the campground anyway. The road ended in orange cones and large Area Closed signs. That option was done.

I sat for a bit and pulled up a few apps, scanning for anywhere nearby. A few miles away, a trailhead parking area came up—another DNR-managed spot used mainly by fishermen. I dropped the coordinates into the GPS. They were slightly off, but close enough.

Eventually I found it: a quiet pull-off along about a quarter mile of Old Highway 40, right on the Provo River, part of the Provo River State Park corridor. As I pulled in, a fly fisherman was walking back to his car, packing up for the night. He waved as he stripped off his waders and loaded his gear, the kind of brief acknowledgment that tells you a place is calm and unremarkable in the best way.

This was the first spot that really felt right. One car pulled in around ten, stayed for about ten minutes, then left. After that, nothing. There was a clean restroom nearby and the steady sound of the river moving through the dark. No traffic noise. No sense of being watched. Just water and cold air settling in.

It wasn’t where I’d planned to end the day, but it was exactly what I needed—a place to stop, disappear, and let the night finish itself.