Drive To Arches

I sometimes wonder where the time goes on certain days. Some days are packed with activity, and by the end I’ve done more than I expected. I come away with enough images that it’s easy to assemble a set of photographs that mirrors the day. This wasn’t one of those days. It didn’t feel wasted, just different—harder to pin down. I couldn’t blame it on lack of sleep. The night along the Upper Provo River had been quiet, level, and easy, with restrooms nearby and no reason to rush the morning.

Google Maps said there was a Starbucks a few minutes away in Heber City. For twenty minutes, I drove loops around the location, but there was nothing there—apparently a future Starbucks. The next closest one, about four miles away, did exist. I settled in there for nearly three hours, catching up on small things: blog edits, photos, emails. The Wi-Fi was solid, it never got overly busy, and the music was unexpectedly good—Brazilian jazz that didn’t demand attention but kept me there longer than planned.

Eventually I left Heber City heading south toward Arches National Park, easing into a stretch of road that felt immediately different from most of Utah. The highway followed the land closely, winding through a long canyon and staying tight to the railroad tracks for miles at a time. Trains still move through here, but the road feels weighted more by what it used to serve than by what passes through now.

What caught my attention were the old telephone lines running alongside the tracks. Each pole carried four wires, evenly spaced—the kind of open-wire system you don’t see anymore. The odd thing was that every line had been cut between poles. The wires were still attached to the insulators, but the ends lay on the ground, again and again down the canyon. It didn’t feel accidental or neglected. It felt intentional, like someone shut the system down and simply walked away. The structure remained. The function disappeared. The corridor felt paused, left exactly where it stopped working.

Tie Fork Rest Area

I pulled into the Tie Fork Rest Area, set slightly back from the road. There were only a few vehicles—a van camper, two trucks, and a couple of cars—spread across a wide parking lot. It was quiet in the particular way canyon rest areas are, where traffic noise fades quickly and the space feels briefly detached from the road it serves.

Inside, it was clear this wasn’t just a basic restroom stop. One wall was lined with brochures and maps laid out with some care—Utah byways, regional geology, mining history, small towns scattered across the eastern part of the state. Interpretive panels explained the corridor itself: the railroad running alongside the highway, the mines carved into these hills, and the industries that once moved steadily through this canyon. It felt halfway between a rest area and a small information center, a place designed to slow you down rather than push you back onto the road.

Out back was a small museum-style structure, closed when I was there, but even from the outside it suggested there was more context here than usual. Reading through the displays inside the main building, I learned that this rest area replaced the original Tucker stop farther up the canyon, a dangerous curve at the bottom of a steep grade that was eventually buried during a highway realignment. The replacement was built a few miles downstream and designed to echo the rail town that once existed here—modeled after an early twentieth-century train depot, complete with a replica roundhouse and a non-functional steam locomotive. Knowing that gave the place a different weight. It explained why it felt more deliberate than most highway stops, less disposable. I grabbed a Utah map, went back to the van, and took a short nap before moving on.

South of Tie Fork, the road began to drop. Not sharply, but steadily. The descent felt measured, the canyon opening and tightening in alternating stretches as the elevation slowly fell away. The air felt heavier. The terrain less alpine, more industrial and worn.

Castle Gate

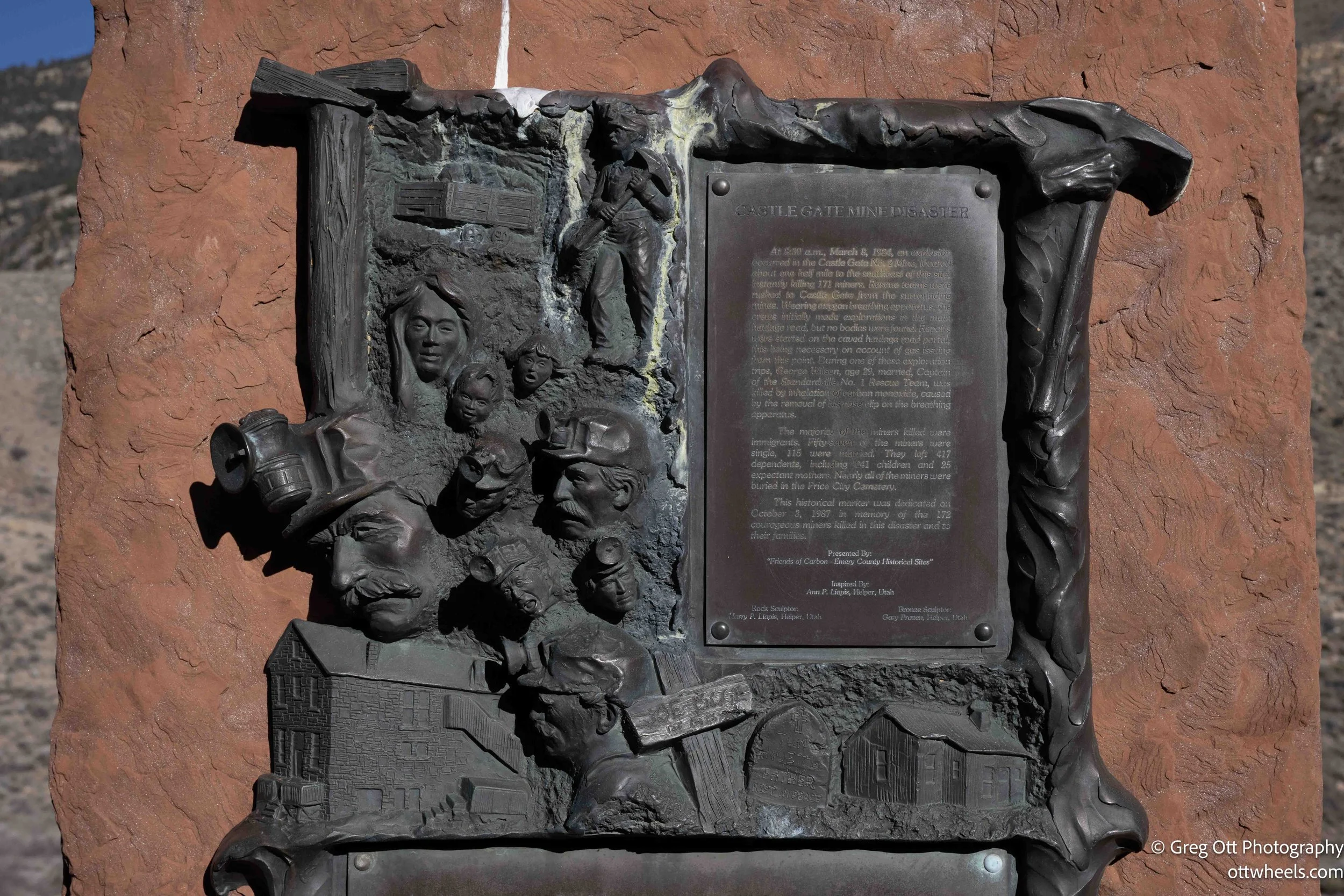

Not far down the road, I pulled over where a cluster of memorials stood close to the highway. The plaques weren’t general or symbolic. They were specific. One described the Castle Gate mine disaster of 1924, when an underground explosion killed 172 miners almost instantly. The blast moved through multiple tunnels, collapsing workings and cutting off escape routes. Many of the men were immigrants, and entire families in nearby company towns were wiped out in a single day.

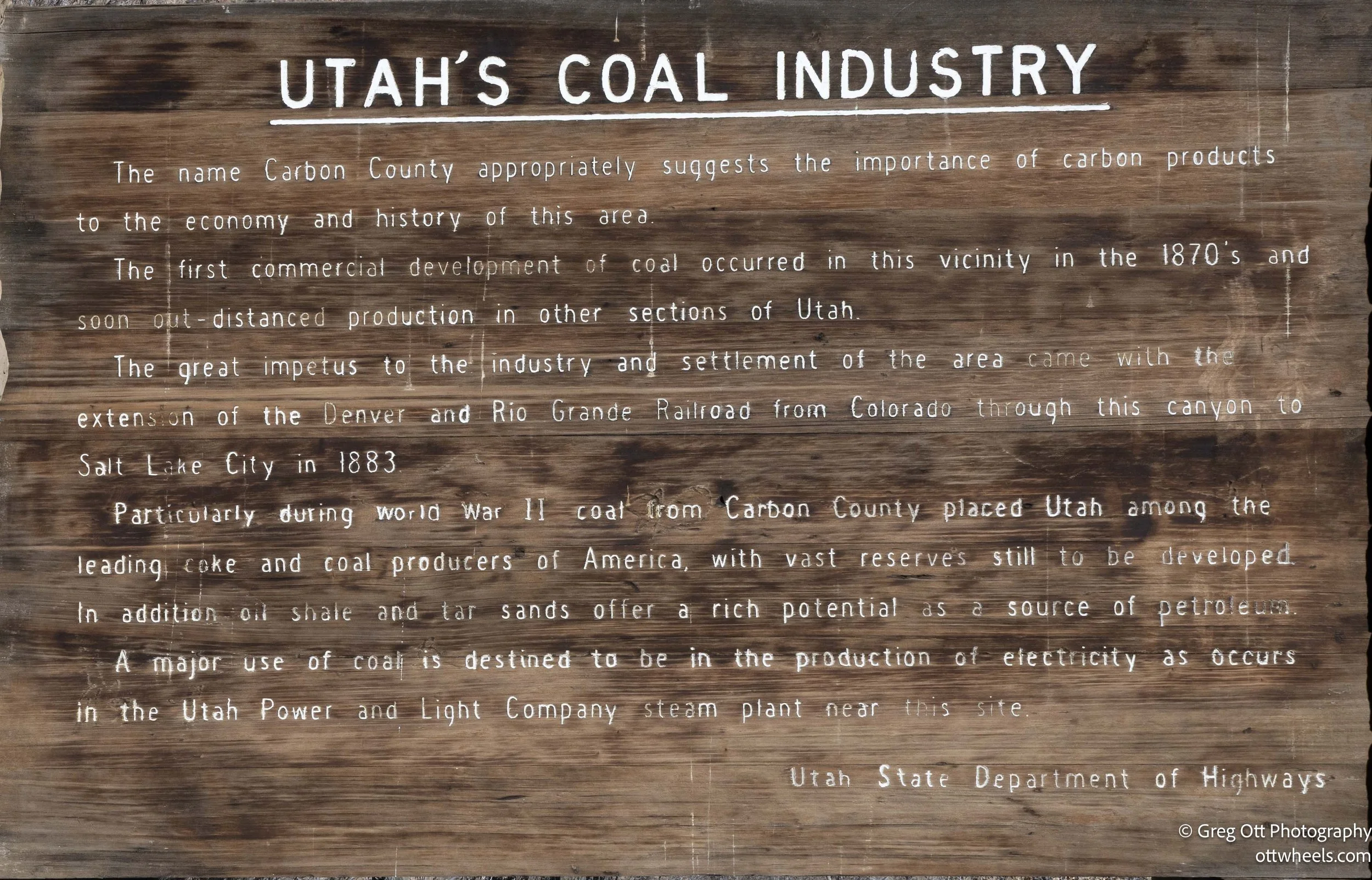

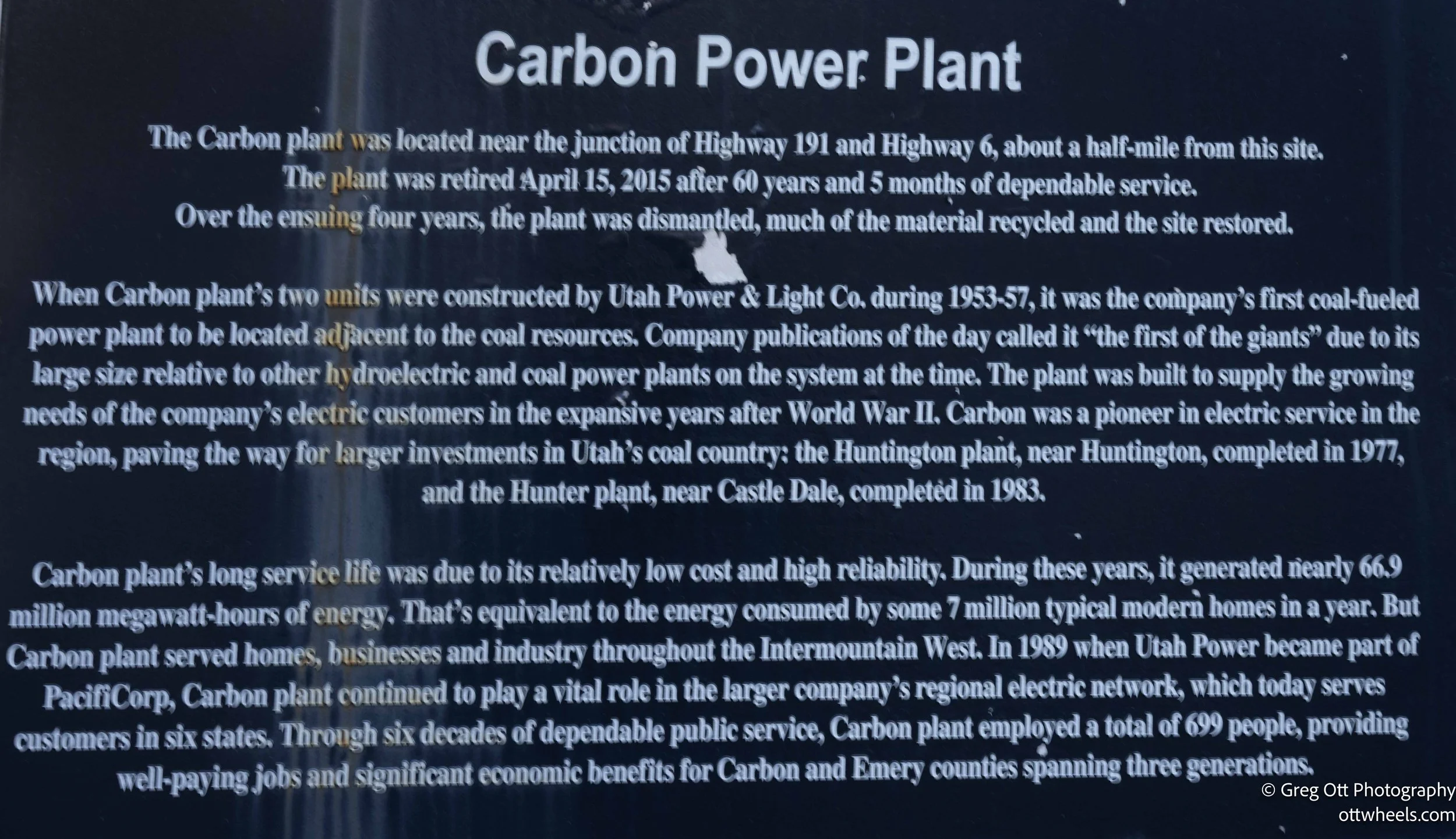

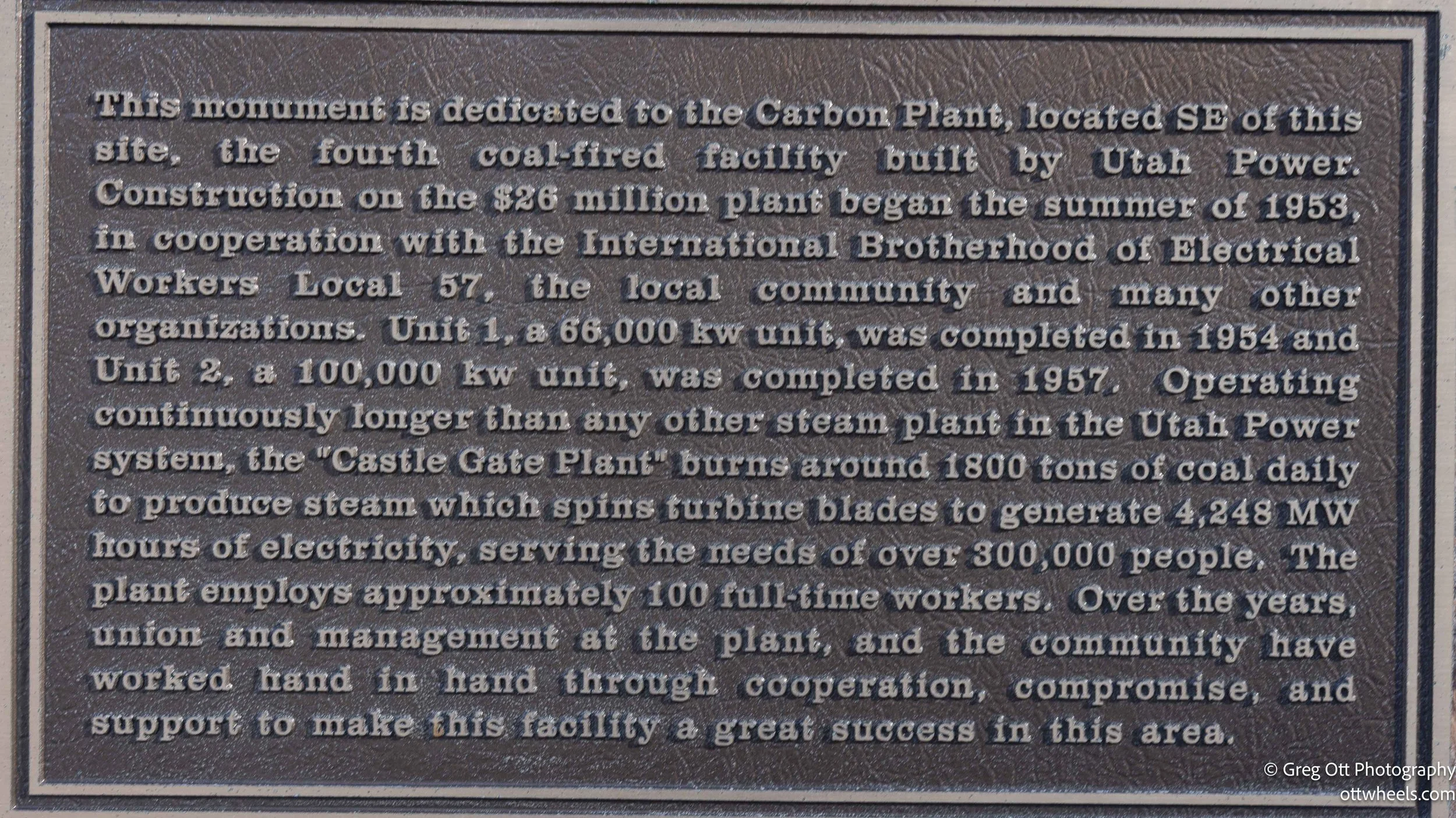

Another plaque explained how coal tied everything here together. The coal pulled from these mines wasn’t only shipped out by rail—it was also used to fire the Castle Gate electrical plant, which began construction in 1953. Power generation, mining, and transportation weren’t separate industries; they were parts of the same system. Coal came out of the ground, fed the plant, powered operations, and moved along the corridor I was driving through. Standing there, with the railroad on one side and the highway on the other, it was easy to see how completely the county had been organized around that logic. Carbon County wasn’t named for symbolism. It was named for function. When the coal stopped moving, the rest of the system slowly unraveled with it.

Back on the road, the land began to change again. The canyon loosened its grip, the industrial remnants thinned out, and the geology shifted toward the massive rock and desert forms of southern Utah. There was no sign marking the transition, just the absence of what had been there before.

It wasn’t a scenic drive in the way Utah usually announces itself. There were no overlooks, no pull-outs asking you to stop. The road just kept moving, close to the tracks, past cut wires hanging slack from old poles, past memorials easy to miss if you weren’t looking for them. Nothing demanded attention, but enough accumulated that I stayed alert without quite knowing why.

By the time it was closing in on five, the sky was still bright blue and the sun strong. About twenty miles north of Arches National Park, I turned off the highway onto a rough BLM road, deeply rutted and direct about its rules: camp only in designated spots, and if they’re full, move on. I never saw anything clearly marked, but the ground told its own story—stone fire rings, tire tracks, places others had stopped before me. I pulled in beside one of them and shut the engine off. With the side door open, the late sun filled the van while I made dinner. The road was close enough to know it was there, but far enough away that it stayed quiet.

It had been a day of mostly driving. Not much to photograph. Not much to point to. And by the end of it, that felt just fine.