Spiral Jetty, Rails, and a Night in Ogden

Spiral Jetty

I spent the night in the small parking lot directly in front of Spiral Jetty. Around 7 a.m., I woke to a blue glow filling the windshield. Everything—from the ground out to the horizon—was washed in layered shades of blue, like a restrained gradient climbing into the sky. It reminded me of Pablo Picasso’s Blue Period—not in subject or mood, but in the way a single color quietly took over everything.

I got dressed quickly and grabbed the camera, hoping to catch it before it slipped away. Within five minutes, the light shifted. The blues thinned out and the scene flattened into something more ordinary and muted. The moment was brief, and then it was gone.

The night itself had been quiet. A couple pulled in around eleven and slept in the back of their car, bundled into sleeping bags. I looked out when they arrived, more curious than anything. Their lights went out almost immediately, and I never heard them leave. By morning, a black truck was parked at the far end of the lot, empty. I assumed its occupants had headed down the Spiral Jetty trail off to my right.

I wasn’t hungry, and I already had the tripod and camera in hand. The lake was noticeably low. There was no water around the jetty at all, a clear sign of how much the level has dropped. Even at its fullest, the water here is shallow—maybe a foot or two—but this was the change I’d read about so often. Less winter snowfall, less summer rain, and water tables falling across the entire basin. Standing there, it felt less abstract than it does on the page.

I spent about thirty minutes photographing, listening, and watching the light move across the landscape. In the back of my mind, I was already dreading the drive out. The last seven miles of washboard dirt road had been rough coming in. The remaining twelve miles beyond that would be easier.

I packed everything carefully and started back. The first seven miles took forty-five minutes, slow and deliberate. Once I reached the smoother section, I pulled over and took a break, looking out over the long valley stretching away in front of me. The black truck from the parking lot came up behind me, slowed, and the two women inside smiled and waved as they passed. I grabbed a few photos, got back in, and continued on—now able to drive a comfortable forty miles per hour.

Golden Spike National Historical Park

From there, I headed to Golden Spike National Historical Park and registered for the train barn tour. It was scheduled to start in twenty minutes at 10:30, just enough time to grab breakfast and a coffee. We met in the lobby, where the ranger gave a brief overview of the site and its history before asking us to follow her to the train barn in our own vehicles.

She began by talking about the ceremonial spikes used in the The "Last Spike" ceremony . The famous golden spike was only one of several driven that day. There were also spikes made of silver, gold-and-silver alloy, and iron. The golden spike itself was never meant to stay in the ground; it was removed shortly after the ceremony and eventually donated to Stanford University. Other commemorative spikes were claimed by rail executives or later collectors, and a few replicas were produced years afterward for display and fundraising. What remains at Promontory today is symbolic, but the story behind those objects is very real.

The significance of the park is simple and enormous: this is where the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads met in 1869, completing the first transcontinental railroad. It permanently changed how the country moved—goods, people, information—and tied the coasts together in a way that had never existed before. The two locomotives that met here were Jupiter, arriving from the west, and Union Pacific No. 119, arriving from the east.

The air temperature was in the high forties and felt warmer in the sun. Outside the barn, the ranger explained that the two engines burned different fuels. Jupiter burned wood, which was plentiful in the west. No. 119 burned coal, which burned hotter and cleaner but wasn’t readily available this far west at the time. A small pile of coal sat nearby, and she mentioned that the park is fortunate to still have a supply source in Colorado—though that could change if the mine closes.

Before we went inside, she told us we were free to walk around the engines as long as we stayed behind the yellow lines and plastic chains. No touching, especially the brass. Over one thousand volunteer hours a year go into polishing the brass alone.

Inside, I was struck by how brightly painted the engines were. Most steam locomotives I’d seen were black and utilitarian. She explained that early locomotives were often brightly painted before railroads standardized their designs and the engines became pure workhorses. The original plans for these locomotives no longer exist, and both originals were scrapped long ago. To build the replicas, the park commissioned more than seven thousand hand-drawn plans—this was all done before CAD. She showed me one of the detailed drawings of Jupiter and explained that, using photographs and computer analysis, they’ve determined the replica’s length is within four inches of the original.

Each year, parts of the engines are cleaned, repainted, or refurbished as needed. While we were there, Jupiter’s front wheels and blue cowcatcher were sitting forward of the engine. Using historic photographs, the park has been able to repaint the locomotives accurately over time based on paint samples found in the original manufacturing sites. On No. 119, there’s a painted image of Paul Bunyan on the tender. The ranger told me they’ve never found a photograph of the other side of the engine from the north; all known images were taken from the south or didn’t include the tender at all. The painting is an educated reconstruction.

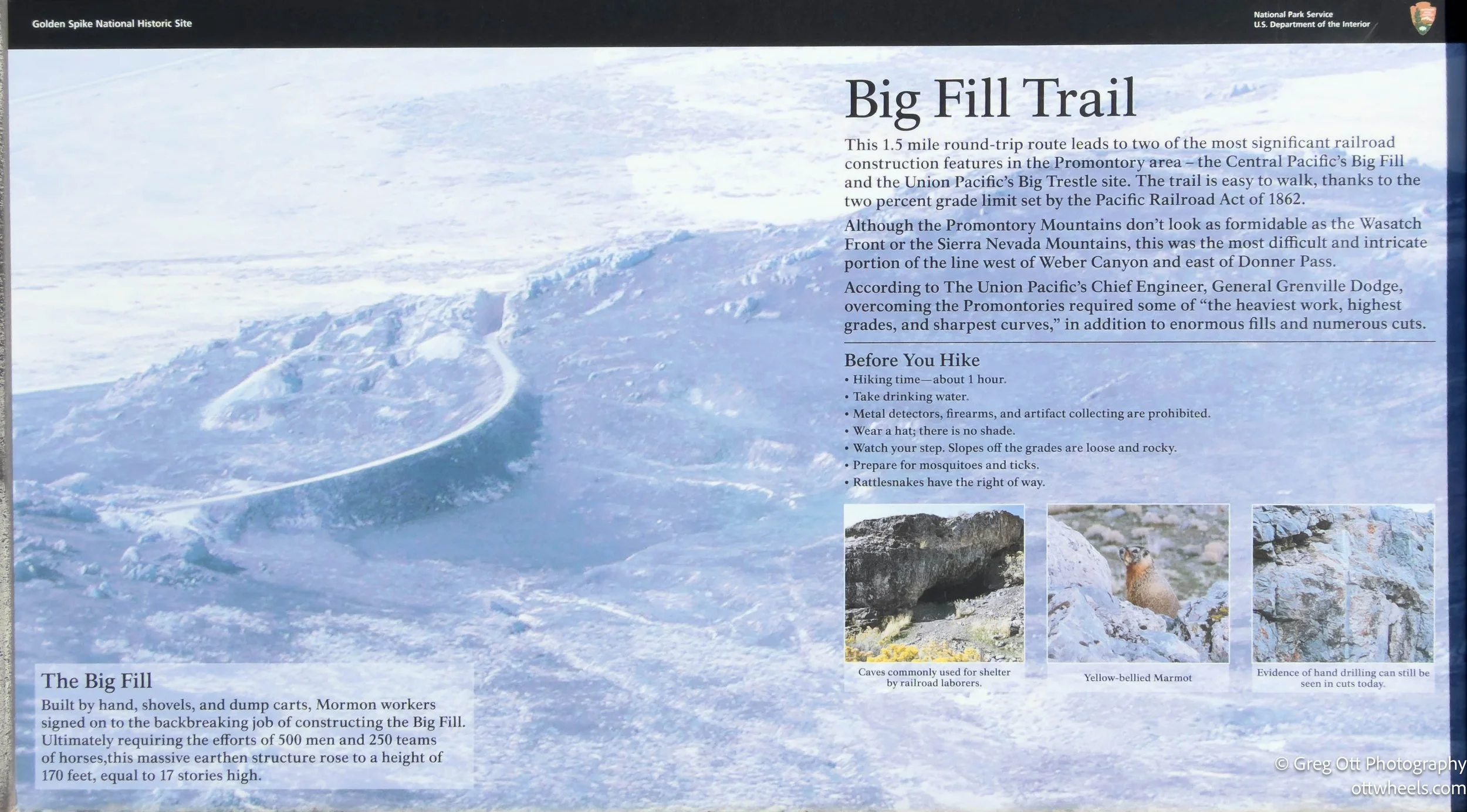

The ranger was exceptionally knowledgeable, and the tour felt less like a script and more like an open conversation. There were only three other people with me. One asked about the Big Fill and the trestles nearby. The ranger explained that the wooden trestles are long gone—removed or scavenged decades ago. She mentioned a trail that leads out to the Big Fill, where you can walk the massive earthwork and see where the trestles once stood. Just like that, my plans shifted again.

The Big Fill

I found the trailhead and pulled into the parking lot. One other car was there. On AllTrails, the hike was listed as a five-mile round trip. Perfect. Along the trail were numbered signs with a phone number printed on them. The idea was that you’d call in, enter the number on the sign, and hear an explanation of what you were looking at. Unfortunately, there wasn’t enough cell service to even complete the call. I listened to the recordings later, once I had coverage.

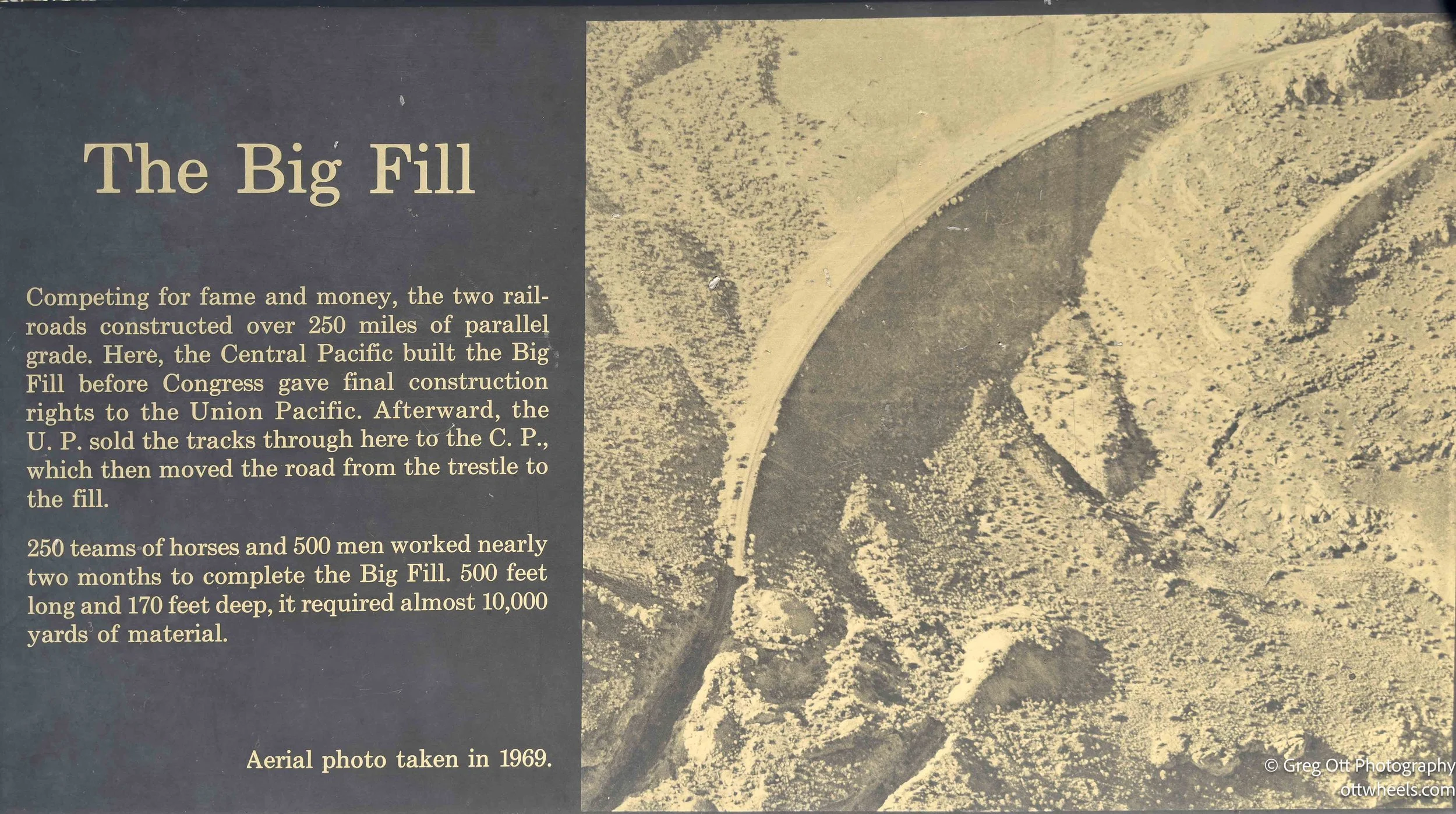

The Big Fill replaced the famous wooden trestles that once spanned a wide gap nearby. I can’t image riding across them. Those trestles were quick to build and essential in the early days, but they were never meant to last. The massive earthen fill that took their place was a more permanent solution, designed to stabilize the line and keep trains moving reliably through this low stretch of land.

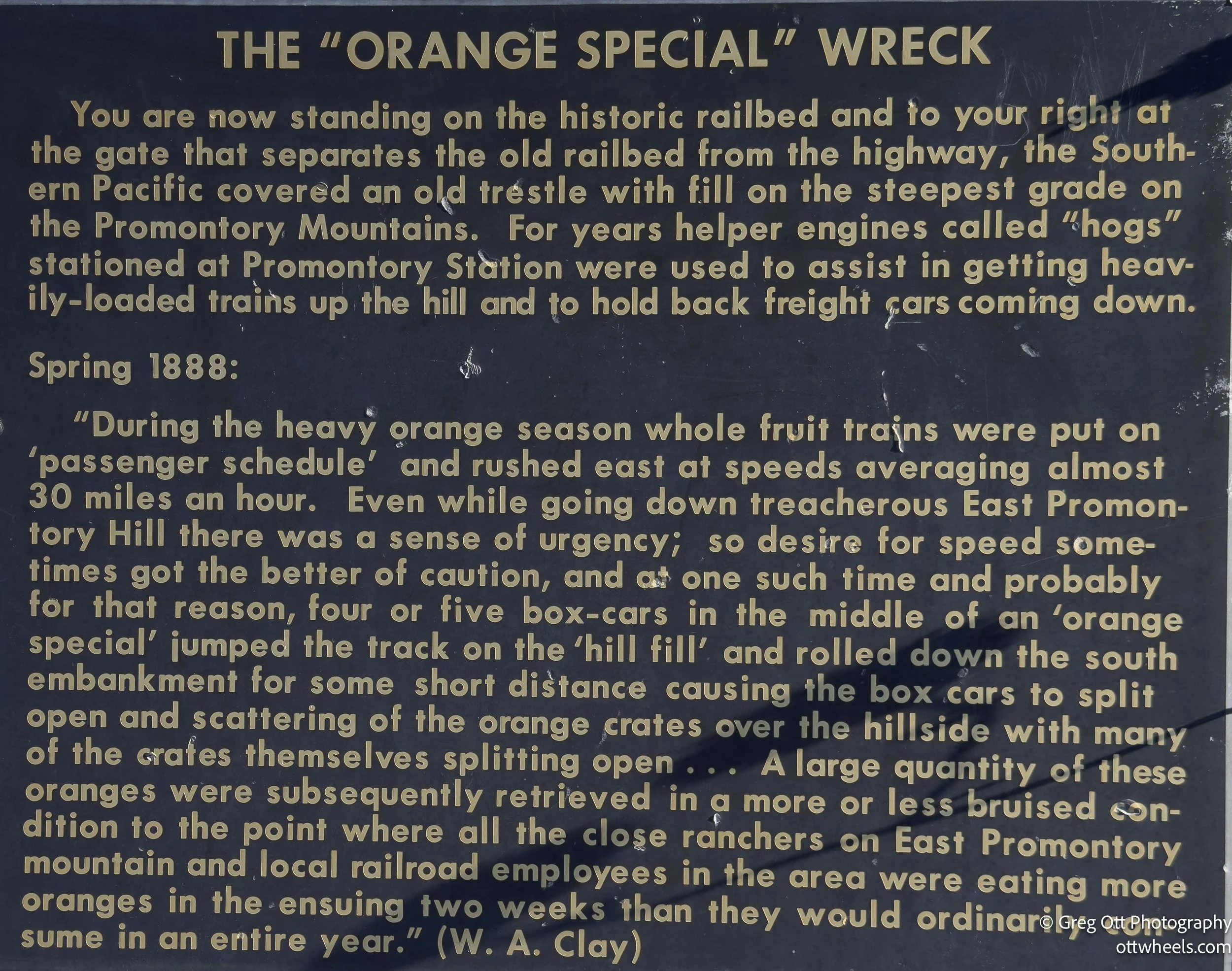

Near the Big Fill, there’s a modest marker for the Orange Special wreck, a reminder of how quickly the transcontinental railroad reshaped everyday life. Once the rails connected California to the East, oranges—previously rare, expensive, and seasonal—became wildly popular, turning citrus into a national obsession. Speed suddenly mattered. Trains like the Orange Special were rushed east to get fresh fruit to market before it spoiled, and that urgency pushed infrastructure hard. In 1903, uneven settling in the newly built fill caused the train to derail here, several cars sliding down the embankment. Two people were killed, many were injured, and the accident exposed the tension between demand and engineering reality. Standing there now, it’s easy to forget that something as ordinary as an orange once moved fast enough—and mattered enough—to derail a train.

The trail itself is a steady, gentle two percent grade, following the old railroad alignment. It’s wide and gravelly, built for trains, not feet, which makes for easy walking. As you move farther out, the scale of the Big Fill becomes clear—a massive earthen embankment built to replace the temporary wooden trestles that once crossed this low area. Those trestles were quick to build but vulnerable, and they were never meant to last.

From the top of the fill, the views open up. Below, a large solar field spreads across the valley floor, a modern echo of industrial ambition layered onto the same landscape. A long procession of ATVs rode by in the distance, the noise echoing off the mountains.

In the distance, snow-capped mountains line the horizon. Standing there, you can trace the straight, deliberate line of the railroad cutting through a place that otherwise bends and rolls with the land. A gas pipeline stretches into the distance, a line marking it location in the landscape. It’s quiet, exposed, and oddly humbling up here. I walked out the full distance, turned around, and took my time coming back. There’s a small town at the bottom of the railtrail and Northrop Grumman has a huge facility there which manufactures and tests large solid-fuel rocket motors for U.S. defense and space programs. As I drove away from this area, I noticed the Northrop sign, “Safety First - Always” and remembered my kaizen days.

Ogden

By the time I headed toward Ogden, it was nearing five p.m. The drive took about an hour. The sunset was spectacular—pools of standing water reflecting steep mountains nearby and softer shapes in the distance. I wanted to stop for photos more than once, but there was nowhere safe to pull over. Sometimes it’s better to just let a moment pass without trying to claim it.

I filled up at a Shell just outside Ogden and headed downtown for dinner. Table 25 had great reviews and an interesting menu, which doesn’t always mean much, but it was Sunday evening and I found parking immediately. The trees downtown were wrapped in bright LED lights, giving the area a festive feel. It was mid-January, and I wasn’t sure if the lights stay up year-round, but they were still glowing.

I was seated at the bar, which suited me fine. I wasn’t in a rush and enjoyed the energy behind it. They asked for my ID—apparently there’s a new Utah law requiring everyone to be carded to sit at the bar. I’m rarely carded anymore, so this was new. They asked if I worked for a certain group or acronym I didn’t recognize. I said I had no idea what that was. “Good answer,” they said, and let me stay. Utah continues to surprise me—much to admire, and some things that feel unnecessarily restrictive. I wasn’t even planning to drink.

A couple to my right leaned over and offered recommendations, saying they eat there all the time. I ordered the grilled Aki tuna and stuck with water. The bartender was friendly and made the whole bar feel comfortable. Conversations flowed on both sides of me. Two people, strangers, down the bar were deep into a discussion about AI; both turned out to have computer science degrees (they made it known). Sometimes I could hear every word, other times the room dissolved into a low hum.

Around seven, a couple named Emily and Mat arrived. The hostess asked if I minded if they sat next to me. I moved my bag and said of course. I don’t remember exactly how the conversation started, but it never really stopped. We talked about travel, hiking, West Virginia, trips to Iceland, Buenos Aires, Japan, and skiing. Emily had once worked at Snowbird and was genuinely happy to hear I’d had a good few days in Cottonwood Canyon. She was born on the East Coast in Virginia, while Mat was born and raised in Utah. They mentioned plans to move back east at some point, a familiar tension between where you start and where life takes hold.

As the conversation unfolded, Emily mentioned that she had studied photography at the university, which opened up a whole new set of paths to explore. She shared thoughtful recommendations for places around Moab that went beyond the usual stops. Mat, fluent in Japanese and having lived there for two years, talked about time he’d also spent exploring Alaska, offering a perspective that made those distant places feel grounded and lived-in rather than abstract.

It turned into one of those rare dinners where time seems to fall away. It reminded me of My Dinner with Andre—not because it was dramatic, but because it was unforced and deeply human. The restaurant closed at nine. We were still talking at nine-thirty. They invited me to park on the street near their place a few miles away. I hadn’t figured out where I’d stay yet, so I accepted. We paid and left the restaurant.

The night stayed with me, a reminder that the best parts of travel often have less to do with where you are and more to do with who you happen to meet.