Lone Rock to Gooseneck State Park Utah

I woke in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area within eyesight of Lone Rock. I was alone in the campsite looking at the large face of a mountain. The sun was bright and there wasn’t a sound in the area. I got out to look at the view. The air was crisp and fresh. I lingered looking a the large rock in the distance. Eventually, I made oatmeal, with blueberries, a banana, an omega-3 mix of nuts and seeds, almond milk and a large dash of maple syrup. A hearty breakfast for the long drive to Gooseneck State Park in Utah.

Once again, I’d have to drive back into Arizone to get to Utah. Glen Canyon prevents direct access. I stopped in Page again to top the gas tank up. I’m slightly paranoid about running out of gas in the middle of nowhere. While getting gas, I made myself an espresso for the road.

I didn’t get very far before I came to the Glen Canyon Dam. This wasn’t on my itinerary and wasn’t in Utah, but I had to stop. The Dam sits just downstream from Page, Arizona, holding back the Colorado River to form Lake Powell. Construction started in 1956 and wrapped up in 1966, during a period when the West still believed big engineering could solve big problems. The dam rises about 710 feet out of the canyon and was built to do a few very specific things: store water, control floods, and generate power. Its hydroelectric plant can produce roughly 1,320 megawatts, supplying electricity across much of the Southwest. The idea was simple and ambitious—lock away water in wet years so it would be there in dry ones, and turn that stored water into power along the way.

Today, the story feels very different. Years of drought and overuse have pushed Lake Powell to unsettling lows, sometimes close to the point where power generation becomes difficult or impossible. The Bureau of Reclamation, which operates the dam, has been juggling releases from upstream reservoirs and changing how the dam runs just to keep the system functioning. Glen Canyon Dam still plays a critical role in managing the Colorado River and meeting water obligations downstream, but it has also become a symbol of how tight things have gotten in the West. Standing here, it’s hard not to feel the weight of that shift—from confidence and control to careful management and uncertainty—all poured into concrete at the bottom of a canyon.

I drove toward Monument Valley and reached Kayenta, about an hour south. I’d seen a sign for a Navajo Code Talkers exhibit but couldn’t track it down. Later I learned it was tucked inside the Burger King—one of those very Kayenta details you only figure out after the fact. Just outside town, though, there was no missing the huge solar power generation field. Rows and rows of panels stretched across the desert, catching the light in a way that felt both futuristic and perfectly at home in this landscape.

This is the Kayenta Solar Project, built and owned by the Navajo Nation. It’s one of the largest renewable energy projects on tribal land and a clear shift from the region’s long reliance on coal. Seeing it up close, near a place as iconic and ancient as Monument Valley, made the contrast impossible to ignore. The panels sit quietly, no smoke stacks, no noise—just a steady, deliberate presence. It felt less like an industrial site and more like a statement: the land still provides, just in a different way now.

Monument Valley seems to straddle the Arizona–Utah border in a way that makes the line feel almost theoretical. I passed the KOA I stayed at the last time through; it was completely empty this time, the gates open but no one home. I pulled over at the border to get a photo of the Utah sign, which turned into a bit of chaos. Cars were parked on both sides of the road, people darting across traffic while trucks blasted through at 65 mph. It felt oddly tense for such a scenic spot. Still, I was officially back in Utah. In the last two days, I’d probably spent more time driving through Arizona to reach places in Utah than I’d actually spent in Utah itself.

One of the biggest surprises came just north of there. A simple roadside sign read, “Forrest Gump Point.” This is the stretch of US-163 made famous in Forrest Gump, where Forrest stops running, turns around, and says, “I’m pretty tired. I think I’ll go home now.” That single moment turned an ordinary highway into a destination. People were pulled over everywhere, standing in the road, lining up the same view toward the Mittens, phones and cameras out. It’s strange how a few seconds of film can permanently pin a place to the map. You’re just driving north through open country—and suddenly everyone stops.

As I continued north, a snow-covered mountain range came into view, and with it a familiar pull to go skiing. I stopped several times to take photos of the white-capped peaks rising behind darker ridgelines in the distance, framed by open prairie and a deep blue sky. The stops were a good excuse to stretch my legs and slow down long enough to really look around. It’s barren out here, yet clearly lived in. A few trailers sat together at the end of a long dirt road, trucks parked side by side. I didn’t see any power lines and found myself wondering how they get electricity.

Just north of Monument Valley, I passed through Mexican Hat, a tiny place pressed right up against the San Juan River. I couldn’t stop in town for photos—a truck was riding close behind me and there’s nowhere to safely pull off—but a few miles north I turned down a dirt road and finally got a clear look at the rock formation the town is named for. Mexican Hat Rock sits out on the open desert, a flat, wide boulder balanced on a narrow stem, unmistakably shaped like a sombrero. From there, you can also see how tightly the town is wedged into the canyon. There’s a hotel built right into the side of the rock wall above the river, looking less constructed than anchored in place. Mexican Hat is small enough to blink past, but once you slow down—even briefly—it feels defined by its geology as much as its name.

My destination for the day was Goosenecks State Park. As I approached the park on Utah Route 261, there were warning signs for trucks, RVs, and vehicles with trailers, listing a ten percent grade, tight switchbacks, narrow roads, and no guardrails. It wasn’t clear exactly where these dangers were supposed to be, so I proceeded cautiously. I made it all the way to the park without seeing anything particularly alarming—those concerns would make more sense the next day.

I pulled up to the entrance station, which was unmanned. A sign with a QR code explained the camping setup: first come, first served, ten dollars per night. There were two parking areas for campers, with four sites each. I’m not sure how they strictly control the number of campers, because there was clearly room for more than eight vehicles spread along the rim.

The views from the rim are immediate and overwhelming. The San Juan River is carved into the landscape below in a series of tight, looping bends that look almost impossible from above, like a ribbon laid down and pressed into stone. The canyon drops away abruptly, with sheer walls falling hundreds of feet straight down, and there’s nothing between you and the edge but open air. From the overlook, the river feels distant and quiet, moving slowly through a landscape that looks completely still. It’s one of those places where scale is hard to process; the bends look delicate from above, but you know the river has been at this work for millions of years.

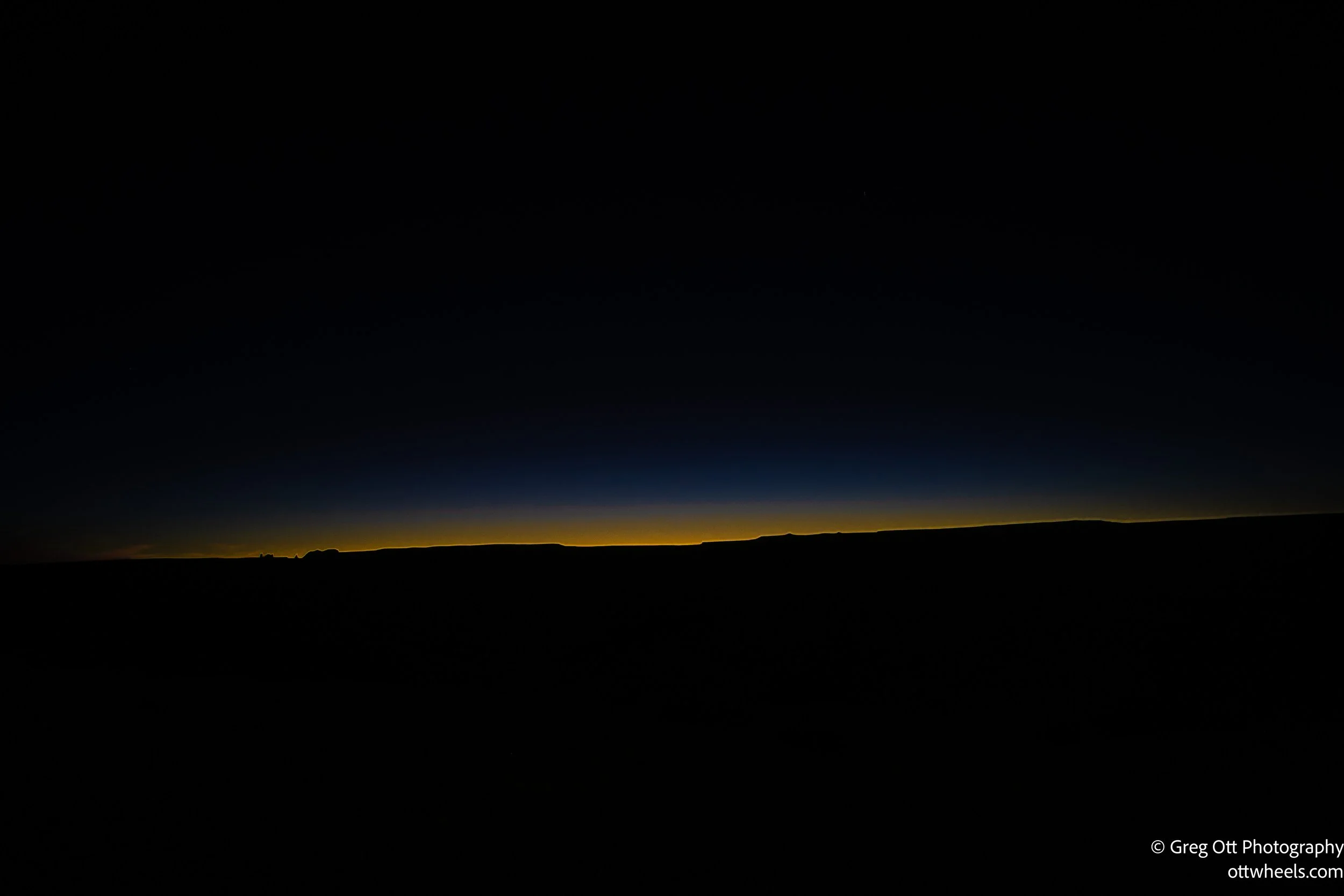

I went out several times and sat at a picnic table overlooking the canyon, taking photos as the light shifted. A lone eagle circled overhead, occasionally diving down into the canyon after prey. As the sun dropped, the scene simplified into contrast: a thin blue-and-yellow sliver of light lingering low in the western sky while the rest of the canyon fell into deep black. I was the only camper there until after ten pm.

The silence felt generous, almost deliberate. You don’t realize how much noise fills your days until it’s stripped away and replaced by nothing but wind, distance, and time. Out there on the rim, the quiet wasn’t empty at all—it was something you could finally hear.