Puebloan Ruins, Dino Tracks, and Valley of the Gods

I woke up on a quiet street tucked far back in Blanding, UT the kind of spot you only find when you’re not in a hurry. There had been almost no traffic overnight, and at 6:30 a.m. the town still felt asleep. I’d passed through Blanding several times already, crisscrossing this corner of Utah, and it was starting to feel familiar in a practical way. I knew there was a Maverik at the far end of town, so I headed that direction, glancing at the dash and noticing the temperature: 18 degrees Fahrenheit. That number has a way of snapping you fully awake.

I stepped out to fill the tank and immediately felt the cold cut through my layers. It didn’t linger—I finished up quickly, climbed back into the van, and drove a short distance to make breakfast. There was plenty of space to park, and I found a flat spot where I could cook oatmeal and warm up before heading out. The sun was just starting to work on the edges of the morning, and I had a full day ahead of me.

Butler Wash Ruins

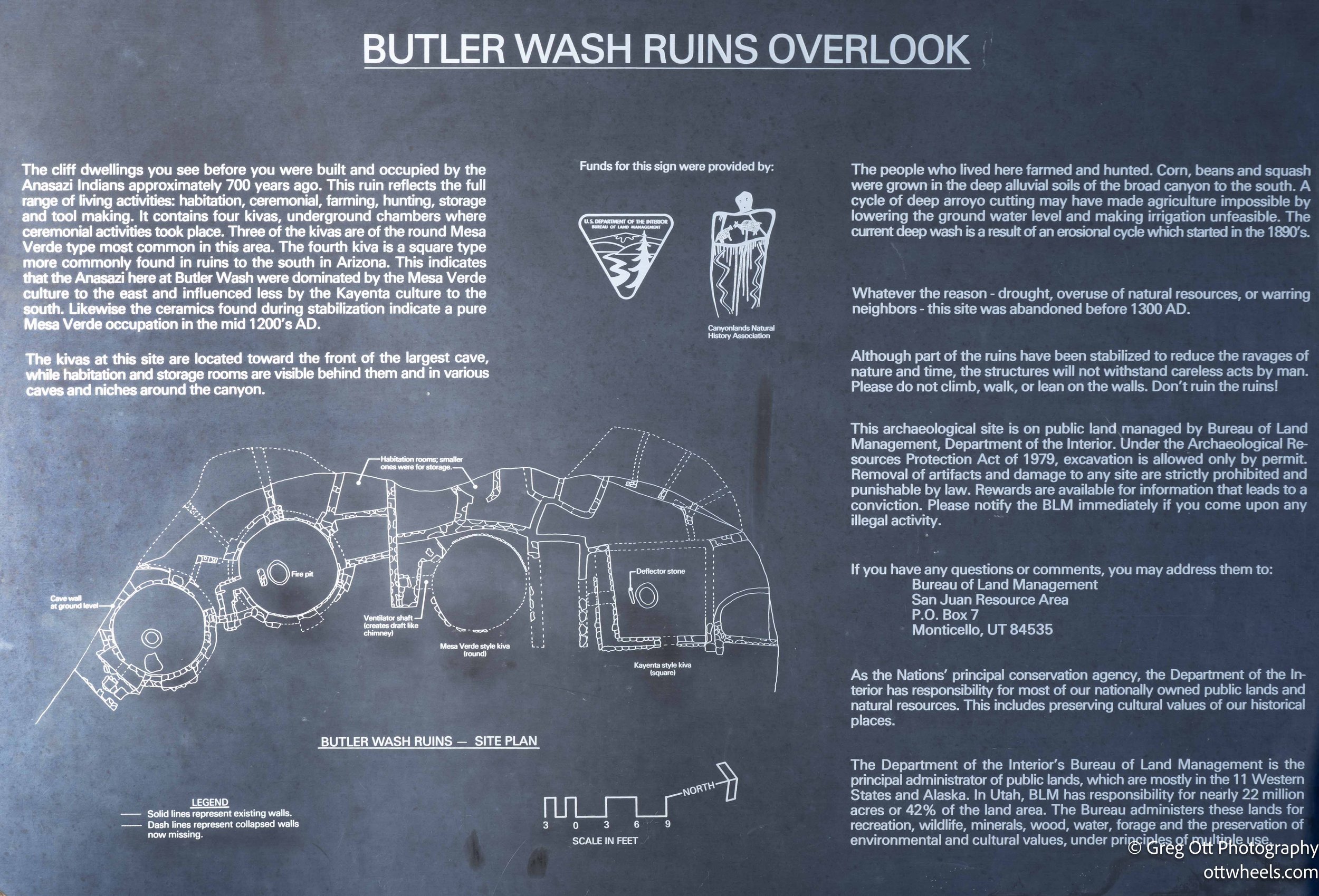

My first stop was the Butler Wash Ruins, just west of town. The site sits within the broader Butler Wash drainage and is one of the more accessible Ancestral Puebloan locations in southeastern Utah. People lived here roughly between A.D. 900 and 1200, during what archaeologists call the Pueblo II and Pueblo III periods. Unlike cliff dwellings hidden deep in narrow canyons, these structures are set into shallow alcoves and ledges above a wide wash—open, readable, and practical.

I’d driven this road the day before without realizing how close I was. When I pulled into the parking lot, I was the only vehicle there. A clean pit toilet marked the trailhead, and I signed the logbook, noticing it had been two days since anyone else had written their name. The temperature had climbed into the mid-30s, and standing in the sun felt noticeably better. I didn’t find the trail on AllTrails, but the notes in the log suggested it was well marked. The hike itself was short, maybe a mile, with a gradual uphill over solid rock rather than loose dirt. At the top, the land opens to an overlook that feels deliberately placed.

From that vantage point, the ruins are easy to read. You can see multiple stone masonry structures—room blocks and granaries—built high into the cliff walls. These elevated storage spaces weren’t decorative or symbolic; they were practical. Keeping corn and other supplies off the canyon floor protected them from flooding, animals, and theft. The masonry is straightforward and precise: stacked sandstone blocks held together with mud mortar, designed to last, not impress. What struck me was how logical everything felt. From a distance, the layout makes sense. You can see where people lived, where they stored food, and how the site balanced access with security. It doesn’t require imagination so much as attention.

The area is managed by the Bureau of Land Management and lies within the boundary of Bear Ears National Monument. Interpretive panels at the overlook explain the architecture, the landscape, and what daily life here may have looked like. You’re not walking among the structures themselves, which helps preserve them, but the view is broad enough that nothing feels hidden. It’s a place that rewards standing still and letting the time scale stretch out in front of you.

While trying to get photos, I put myself in a situation I probably shouldn’t have. Water had hollowed out pockets in the rock, some holding partially frozen puddles. In other places, the sandstone had eroded enough to create open gaps with a clear view straight down to the cliffs below. I got the shots, though not the ones I had hoped for, and then had to scramble across a narrow stone bridge near the edge. It made me stop and think about how the Puebloans accessed these spaces without modern shoes, modern gear, or any margin for error.

Dinosaur Tracks

As I entered Valley of the Gods into Google Maps, I noticed a nearby photo marker for dinosaur tracks. It was only about a mile away and directly on my route, with a short half-mile dirt road leading off the main road. I saw the sign immediately and pulled in. The tracks themselves are preserved in what was once a muddy riverbed or shallow floodplain, dating back roughly 200 million years to the early Jurassic period.

Most of the visible prints are attributed to small to medium-sized bipedal theropod dinosaurs—meat-eaters that walked on two legs. When they passed through this area, the ground was wet and soft enough to record their footprints. Over time, sediment filled those impressions, hardened, and eventually became stone. Erosion did the rest, peeling away layers until the tracks reappeared at the surface. Today, they’re marked with small stone circles, making them easy to spot, at least for now.

I walked around the exposed rock, took a few photos, and tried to follow the patterns—stride length, direction, the subtle differences between prints. It didn’t take long. The entire detour lasted about 30 minutes, and then I was back in the van, rolling toward the next stop.

Valley of the Gods

I drove into the Valley of the Gods without much of a plan, guided mostly by curiosity. The turn off UT-163 is understated, and the road initially feels almost tame. The red sand surface was smoother than many of the dirt roads I’d driven recently, wide enough to be comfortable and nearly empty. There were steep drop-offs in places and no guardrails, but the lack of traffic made it manageable. I wasn’t in a hurry. I let the drive unfold at its own pace, and by the time I found a place to stop for the night, nearly two hours had passed without my really noticing.

What stood out once I slowed down were the formations themselves. Calling them stone monuments didn’t feel quite right, but it was close—tall, isolated towers rising out of open land, each one distinct and spaced far enough apart to feel intentional. From where I parked, the view opened into a wide valley backed by a long, solid wall of rock that seemed to anchor everything in place. It was the kind of landscape that quietly shuts down unnecessary movement. I walked short distances, stopped often, and kept reframing scenes, trying to decide what deserved attention first.

I took far more photos than I expected, circling the same formations and watching how small shifts in position changed the balance of the scene. Eventually, I made dinner and let the light fade without paying attention to the time. Around 8 p.m., I went back out with the camera to try night images. The moon was brighter than I would have liked, and I wasn’t sure how the stars would come through, but the towers held their presence even in the glare. They didn’t disappear in the dark—they just became something else.

I kept working until around 1 a.m., adjusting settings, waiting, trying again, and moving through that quiet stretch where time loses its edges. When I finally stopped, it was more from exhaustion than satisfaction. The images could wait until morning. What stayed with me was the feeling of being alone in a place that didn’t ask anything of me. The Valley of the Gods didn’t announce itself or try to impress. It simply existed, and for one long day and night, I was allowed to exist alongside it.