Quincy Copper Mine — Houghton, Michigan

I woke up at the Walmart in Houghton, MI, to the soundtrack of loud mufflers and slamming car doors — not exactly my idea of a peaceful Sunday morning. I was in town for the Quincy Mine tour at 5 p.m., but I knew there was no way I’d sit in a big box parking lot for the next nine hours.

I remembered a community spot I’d seen when I came through town — Ray Kestner Waterfront Park, just a mile down the hill on the water. I quickly packed up and headed there. There were maybe ten cars in the lot, and I grabbed a spot right at the end, facing the water. For the moment, it was wonderfully quiet.

I slid open the van door and had a perfect view of the Portage Lake Lift Bridge in the distance. I’d thought this was just a river in front of me, but it turns out it’s Portage Lake — part of the Keweenaw Waterway, a manmade and natural channel that cuts right across the Keweenaw Peninsula and links up with Lake Superior on both ends. The waterway essentially slices the top of the peninsula into an island — Copper Island, as the locals call it. The iconic Portage Lake Lift Bridge connects Houghton to its twin city, Hancock, across the channel. Along the walk way, there was a bright red colored plant, which many people took pictures of (no idea what it is).

I made breakfast and settled in to catch up on my blog and sort through photos. It was Sunday, and by noon the park had come alive — families lugging beach toys, kids tearing across the huge playground, joggers and dog walkers cruising past my door. There was a strange haze in the air, I learned later that it was smoke from the fires out west and in Canada.

At one point, as I sat typing, I overheard a little girl ask her mom why the rocks were slimy. The mom, who sounded like a local geology professor, launched into a mini-lecture about algae and rock formations. The kid paused and then said, “But…why?” I heard a lot of those conversations over the next few hours.

Quincy Mine

Around 3:30 p.m., I headed out for my tour. The Quincy Mine sits high above Hancock, perched on a ridge overlooking the Portage Lake channel. I crossed the lift bridge and climbed the steep, winding streets of Hancock before arriving at the sprawling Quincy Mine property.

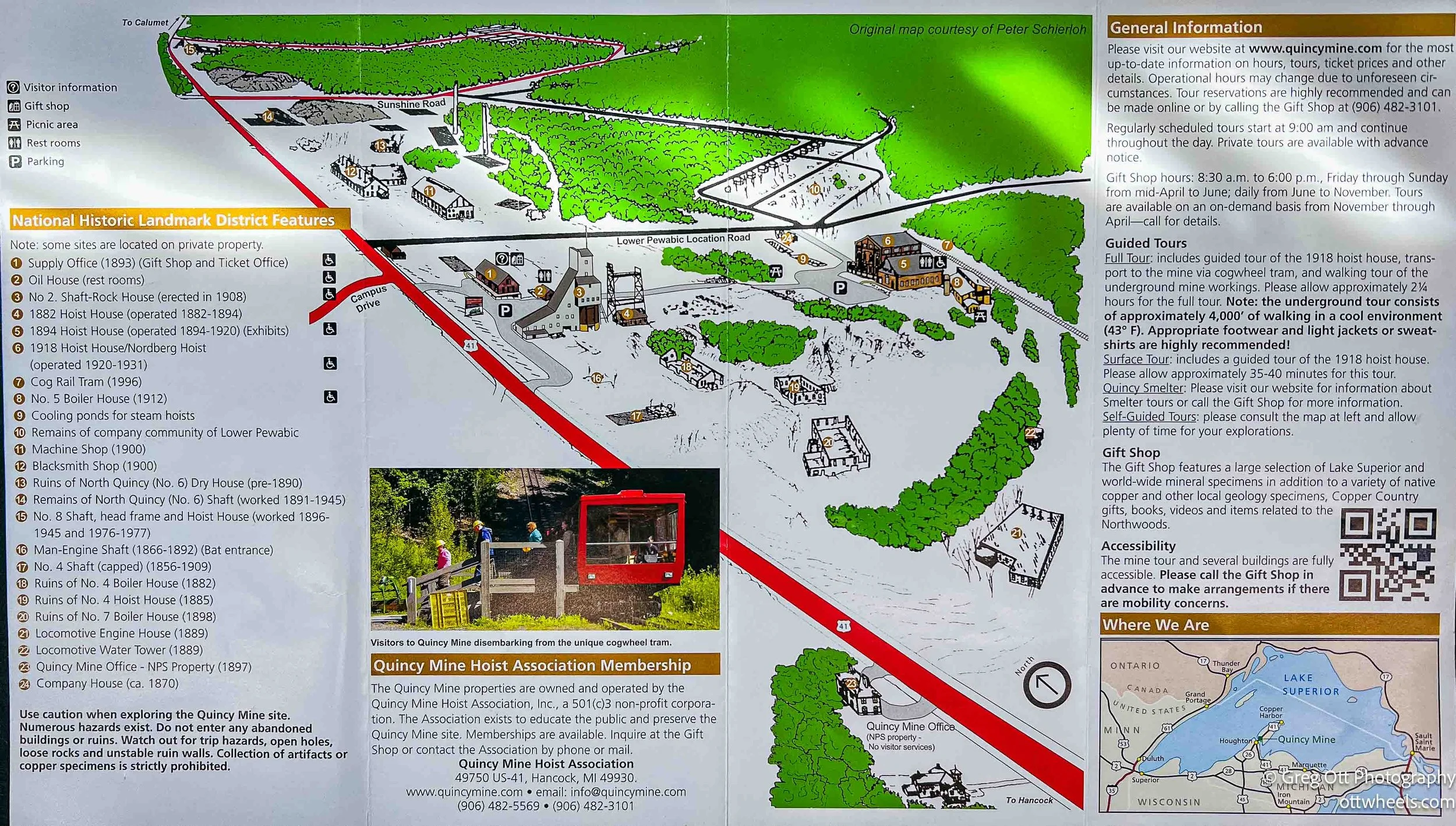

I was early for my 5 p.m. “In the Dark” underground tour. Check-in was easy since I’d done all the paperwork online. They handed me a map and encouraged me to wander. I headed straight for the towering No. 2 Shaft-Rock House — that massive corrugated steel building you can spot from miles away. Inside, a video played on loop, explaining how the shaft house operated to hoist thousands of tons of ore from deep underground.

There are 24 marked points of interest across the grounds. I made it to about half. Scattered all over were old ore cars, giant compressors, and hulking hydraulic equipment, all telling the story of a mine that once earned the nickname “Old Reliable.” Wildflowers now push up between the rusted steel, softening the industrial bones of the site.

The 1894 Hoist House was a highlight. Inside were vintage photos, scale models, and a detailed history of how this mine went from a rugged hillside claim to one of the most profitable copper mines in the country.

The Tour

Our guide was a fifth-year civil engineering student from Michigan Tech, originally from New York City. He’d worked at other historical sites but said the Quincy Mine was special because of how intact it still is. We started the tour with a video and then toured the large Nordberg Hoist. He was a walking encyclopedia, answering every question — from the geology of the Keweenaw to the steam technology that powered these enormous hoists. A couple of engineers in the group lobbed him tough questions about the mineral veins and extraction methods, and he never missed a beat.

Nordberg Hoist

We boarded a bright orange cog rail tram that shuttles you down the side of Quincy Hill to the Level 7 adit. The mine once had a staggering 92 levels, plunging over 9,000 feet below the surface — making it one of the deepest in the world. Everything below Level 7 is now flooded, so this level is as far as visitors can go. It was dug as a horizontal tunnel to drain water naturally out the side of the mountain.

As we exited the cog tram, the cold, damp air blowing out of the tunnel cut right through my clothing. The mine stays so cold because the mountain acts like a giant thermal battery — the deep rock captures and holds the freezing temperatures from winter, keeping the tunnels chilled like an underground icebox year-round. I slipped on my long-sleeved second layer and wished I’d brought a fall jacket. The entrance we used was large, having been expanded for tours by students from Michigan Tech. Off to the side, you could still see the original 5-foot-tall tunnel that the miners once crawled through to reach the working levels.

Inside the drift tunnel, it got cold, damp, and very dark — a perfect setting to imagine what life was like for the miners.

Copper was first discovered in the Keweenaw Peninsula in the 1840s, sparking America’s first true copper rush. The native peoples had mined copper here for thousands of years, leaving behind pits and tools for the newcomers to find. Quincy was founded in 1846, and its consistent profits earned it the nickname “Old Reliable.” It paid dividends to investors every year for more than 50 years straight — an incredible feat for the time.

Mining was brutal work. Many of the miners came from Cornwall, Finland, and other parts of Europe with deep mining traditions. Families often worked side by side — partly because they trusted each other not to make mistakes that could get someone killed. Candles, oil wick lamps, and carbide lamps lit their way in the pitch-black tunnels. Early on, they used hand tools — sledgehammers and chisels. Later, noisy pneumatic drills, nicknamed “widow makers,” became common. The drills spat out fine rock dust, which miners inhaled, leading to deadly lung diseases.

The pure native copper found in the Keweenaw was a blessing and a curse — easy to spot but difficult to break free from the surrounding rock. Ironically, ore with lower copper content was sometimes more profitable because it was easier to extract and process in bulk.

By 1918, Quincy installed the massive Nordberg steam hoist — still the largest steam hoist ever built — to haul rock and miners up and down the deep shafts. Profit always came first. The company owned the miners’ houses, the schools, the grocery stores — even the electricity and water. If you lost your job or got injured, you often lost your home too.

Mining deaths were a grim reality. Official records list well over 200 deaths in Quincy’s history, but that number only includes men who died underground. If you were carried out alive but died later from your injuries, you didn’t count toward the tally.

The work was dangerous, but the miners fought to improve it. The famous Copper Country Strike of 1913–14, sparked by demands for safer conditions and better pay, ended in tragedy and failure. The companies outlasted the unions, and the workers went back underground — many with nothing to show for their fight.

When the tour wrapped up, I walked around the grounds, taking photos as dusk settled in. I briefly thought about parking behind one of the old buildings for the night. But around 9 p.m., while chatting with someone else from the tour, a local police cruiser pulled up and parked in the shadows. That was my sign.

I headed back to my familiar Walmart lot — engines humming and doors slamming — but with a head full of copper country history and the echoes of the miners who once worked by candlelight in the depths of Quincy Hill.