Marquette: Ore Docks and NMU.

I drove to Marquette to see the Iron Docks, where iron pellets are loaded onto ships for their trip to steel-making factories around the Great Lakes. As I approached town, I spotted the Michigan State information center and decided to pull in. It’s a fairly new stop with brochures from all over the area, clean restrooms, and friendly staff ready to answer questions.

Right outside the center, I noticed the Marquette Multi-Use Path — often called the Lakeshore Bike Path — running by. It’s a paved trail that follows Lake Superior’s shoreline through downtown Marquette. It’s super scenic, passing beaches, parks, the famous ore docks, the Marquette Harbor Lighthouse, McCarty’s Cove, and plenty of picnic areas. Locals use it year-round for biking, running, and walking — one of the best ways to soak in the lakeshore views while staying active.

The Beehive

I parked at the park-and-ride lot by “The Beehive,” about a mile further toward Marquette. The Beehive is actually the restored Carp River Charcoal Kiln — a stone kiln built in the 1870s by the Bay Furnace Company to produce charcoal that fueled the nearby Carp River iron furnace, one of the region’s earliest pig iron operations. This beehive-shaped kiln turned local hardwood into charcoal back when coke wasn’t yet available in the remote Upper Peninsula, making it vital for Marquette’s early iron industry.

After decades of harsh weather, the kiln partially collapsed in 2016 but was carefully rebuilt using the original stones by the Iron Ore Heritage Recreation Authority and local masons. Today it stands right beside the Iron Ore Heritage Trail as a quiet reminder of the area’s industrial roots — and a quirky landmark for riders rolling into town.

This town has been shaped by the iron and steel industry — mining, processing, and shipping — and you can still feel that history in every old dock, trail, and building.

-

Marquette’s connection to steelmaking goes back more than 170 years, all rooted in the rich iron ore deposits of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The region’s iron story started in the 1840s when miners first tapped the Marquette Iron Range — one of the oldest iron-producing areas in the U.S. The iron ore mined here today is mostly low-grade taconite, which is crushed, concentrated, and rolled into small round pellets about the size of marbles. These iron ore pellets are more efficient to ship and handle than raw ore and have become the backbone of modern steelmaking.

The Tilden Mine, just southwest of Marquette near Ishpeming, is one of the biggest pellet producers in the area. Once the ore is mined, it’s processed in massive plants right there — ground into powder, separated with magnets, mixed with binders, and fired in huge kilns to form 1/2” pellets.

From there, the pellets make their way by rail to Marquette’s iconic Lower Harbor Ore Dock (now inactive) and the still-active Presque Isle Ore Dock at the north end of town. These towering concrete docks are engineering feats built to efficiently load giant freighters on Lake Superior. The ore docks date back to the late 1800s, when the city’s harbors became vital shipping points for moving Upper Peninsula iron to steel mills around the Great Lakes — mostly in places like Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.

Today, the Presque Isle Dock is still used seasonally to load thousands of tons of pellets onto Great Lakes freighters bound for steel mills, some traveling more than 500 miles by water through the Soo Locks and down to cities like Cleveland, Gary, or Detroit. The old ore docks are so much a part of Marquette’s skyline that they’re a landmark in themselves — a reminder that this little port town has played a big role in building America’s steel and industry for generations.

Superior Dome

Along the way, I spotted the massive wooden dome on Northern Michigan University’s campus. This is the Superior Dome, also known as “The Yooper Dome.” It opened in 1991 and holds the title of the world’s largest wooden dome, built with Douglas fir beams and covering more than five acres. It hosts NMU football games, track meets, and community events year-round — a true landmark that lets locals stay active no matter how deep the Upper Peninsula snow gets.

Side note: The term “Yooper” comes from the abbreviation “U.P.” for Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Locals took the initials “U.P.”, said them out loud — “You-Pee” — and turned that into “Yooper.” It’s an affectionate nickname people up here use proudly to set themselves apart from “Trolls” (the term they use for folks who live below the Mackinac Bridge in the Lower Peninsula!). I see this on billboards.

Presque Isle Ore Dock

I rode out to Presque Isle and turned around to look back at the Ore Dock. The Lee A Tregurtha — with its own interesting history — was being loaded on the south side when I reached it. A long line of ore cars sat on top of the structure, dropping their loads of iron ore pellets into the chutes. The arms along the sides lower periodically to release the pellets into the ship’s holds. It takes about four hours to load these freighters in a controlled way to prevent structural damage to the ship itself. I stood and watched as an arm lowered and the loud rush of ore echoed into the bay. I could see men walking along the top, communicating by radio. I didn’t see anyone on the ship, but I understand the first mate is in charge of the loading operation.

Near the docks there’s an old diesel engine and an example of the ore cars. I stopped to read the plaque and get a few photos — it took me back to trips to the Horseshoe Curve in central Pennsylvania with my kids.

George Shiras Park

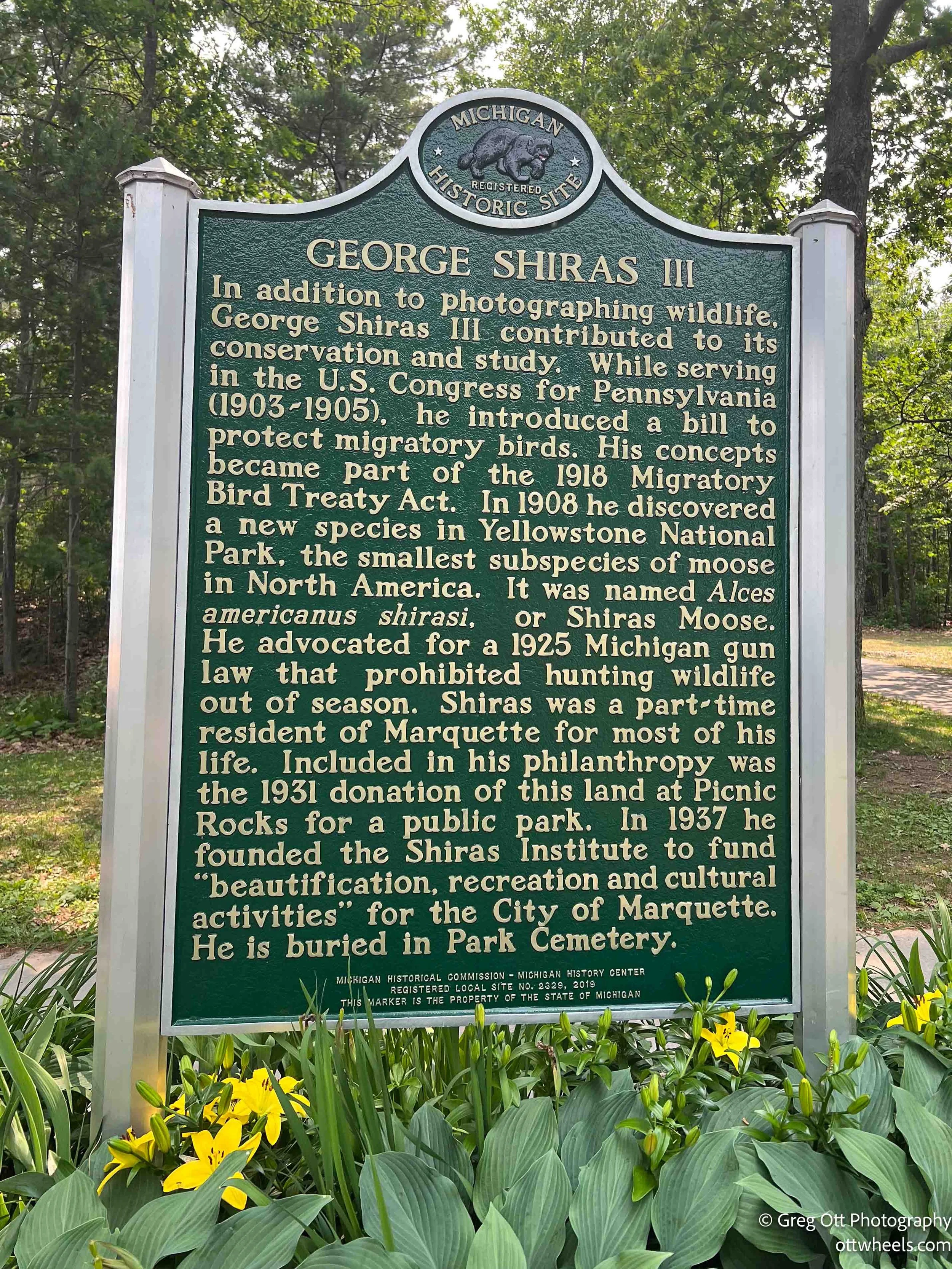

All along the path, there are playgrounds, parks, plaques, and shops. I wasn’t breaking any speed records on this trip — I stopped to read the plaques and take in the views. I stopped to read about George Shiras III, a photographer from Marquette known as “The Father of Wildlife Photography”. He was one of the first to use flash and camera traps in the wild, and his early National Geographic images helped spark America’s fascination with conservation and the outdoors. I had never heard of him before.

A little further along, I came upon some small local shops — a furniture maker, a hippie grocery store, a recycling center, a bike shop. I stopped to chat with the furniture maker. He had some retro 1950s wood coffee tables sitting out front. He’s been in business for three years and said he makes enough to pay the bills and really enjoys what he does. I stopped at the hippie grocery store for some ice cream and people watching. They had an old couch, so I settled in with a big scoop of Maple Nut ice cream. There was a steady stream of locals buying healthy groceries and teenagers coming in for ice cream.

Around the corner I stopped at the bike shop for a new pair of riding gloves. They didn’t have what I wanted but they did have my favorite hydration powder from Scratch Labs. I asked the guy if he knew anything about Sram Eagle electronic shifters on Specialized bikes , and he came out to show me how to align the chain electronically. He solved my skipping chain issue on the spot and said the system would keep auto-aligning itself. It rode much more smoothly on the way back.

I continued into the main part of town, past the Coast Guard center and the Cinder Pond Marina. I’d read that the old part of town was fun — and it was quite a climb up the hills to reach it. At the top, the street slopes down into a long stretch of shops, many painted in bright colors. Some of the shops had brightly colored marquees hanging out front. It definitely had that lively college town vibe. I took a turn and rode through the quiet, well-maintained neighborhood behind it.

One of the most surprising things in Marquette was the Peter White Public Library. This is a massive, beautiful building that I’d expect to see in a capital city or major metropolitan area — not in a town of just over twenty thousand people. The library was founded in 1891 by Peter White, a local businessman, politician, and philanthropist who believed deeply in public access to books and learning. The historic sandstone building sits right in the heart of downtown and still serves as a community hub for art, music, and events. It says a lot about how people here respect education and their right to read.

Old Ore Dock

I rode back down into the lower part of town and saw a parking area on top of a bank where I could get a photo of the old ore dock in the center of town. This dock has been out of service since 1971, when shipping operations moved to the more modern Presque Isle Ore Dock up the shore. The old Lower Harbor Ore Dock still stands as a massive reminder of Marquette’s iron shipping days and how much the steel industry shaped this town. I also learned from a local that the tracks once ran from the top of town right down to the docks — probably right where I was standing.

I slowly made it back to the Beehive and packed everything up. I found a grocery store a few miles away and loaded up on fresh produce.

L’Anse was about an hour away, and I’d been told to stop there for a cinnamon roll at the Hilltop Restaurant. I also wanted to see Canyon Falls nearby. iOverlander showed a place to stay about halfway between the two spots — a state park access road with an area that was semi-paved. It seemed others had stayed there. I was surprised how quiet it was being so close to the highway. It wasn’t quite as peaceful as the National Forest, but there were no trucks or motorcycles roaring by.