International Peace Garden

Dion Lake Morning

I spent the night at Dion Lake, which really is in the middle of nowhere. The silence was absolute, and relaxing. By 7:30 a.m., a thick fog hung over the water, muting the trees and shoreline. After breakfast, I spent some time processing photos from the last couple of days. Around 10:00, I heard the rumble of a truck pulling down toward the dock. The driver got out, checked something at the dock, and then started collecting trash from the barrels around the site. The “barrels” were actually old oil drums with no lids, all of them overflowing. I was surprised they hadn’t been tipped over during the night by animals. He swapped out the bags, loaded them in the truck, and was gone just as quickly.

Driving to the International Peace Garden

From there, it was about a 30-minute drive to the International Peace Garden. The first few miles were on dirt road before I reached the main highway. What’s unusual about the Garden is how you enter: you pass either the U.S. or Canadian border office without stopping. You don’t show your passport until you leave, at which point you’re technically entering one of the two countries. It’s the only place I know of where you drive past the border without actually clearing it.

Entry and First Impressions

The entrance fee was $10, which seemed inexpensive given the scope of what the Gardens represent. The woman at the entrance gave me a map and walked me through the border process again, patiently answering a few questions. Camping is available for $35 a night, with water and electric hookups. Since I was running low on water, I asked if there was a place I could fill up without staying, there wasn’t. I knew I’d find plenty of places to park overnight on my way to my next stop, so I skipped the camping.

The entrance gave me a map and walked me through the border process again, patiently answering a few questions. Camping is available for $35 a night, with water and electric hookups. Since I was running low on water, I asked if there was a place I could fill up without staying, there wasn’t. I knew I’d find plenty of places to park overnight on my way to my next stop, so I skipped the camping.

The Rock Cairn Dedication

At the entrance, I stopped to photograph the massive rock cairn, from the July 14, 1932 dedication, with its plaque that reads: “To God in His Glory, we two nations dedicate this garden and pledge ourselves that as long as men shall live, we will not take up arms against one another.” It’s a bold statement, one that I hope still resonates as much today as it did in 1932 when the Gardens were first dedicated.

History of the Gardens

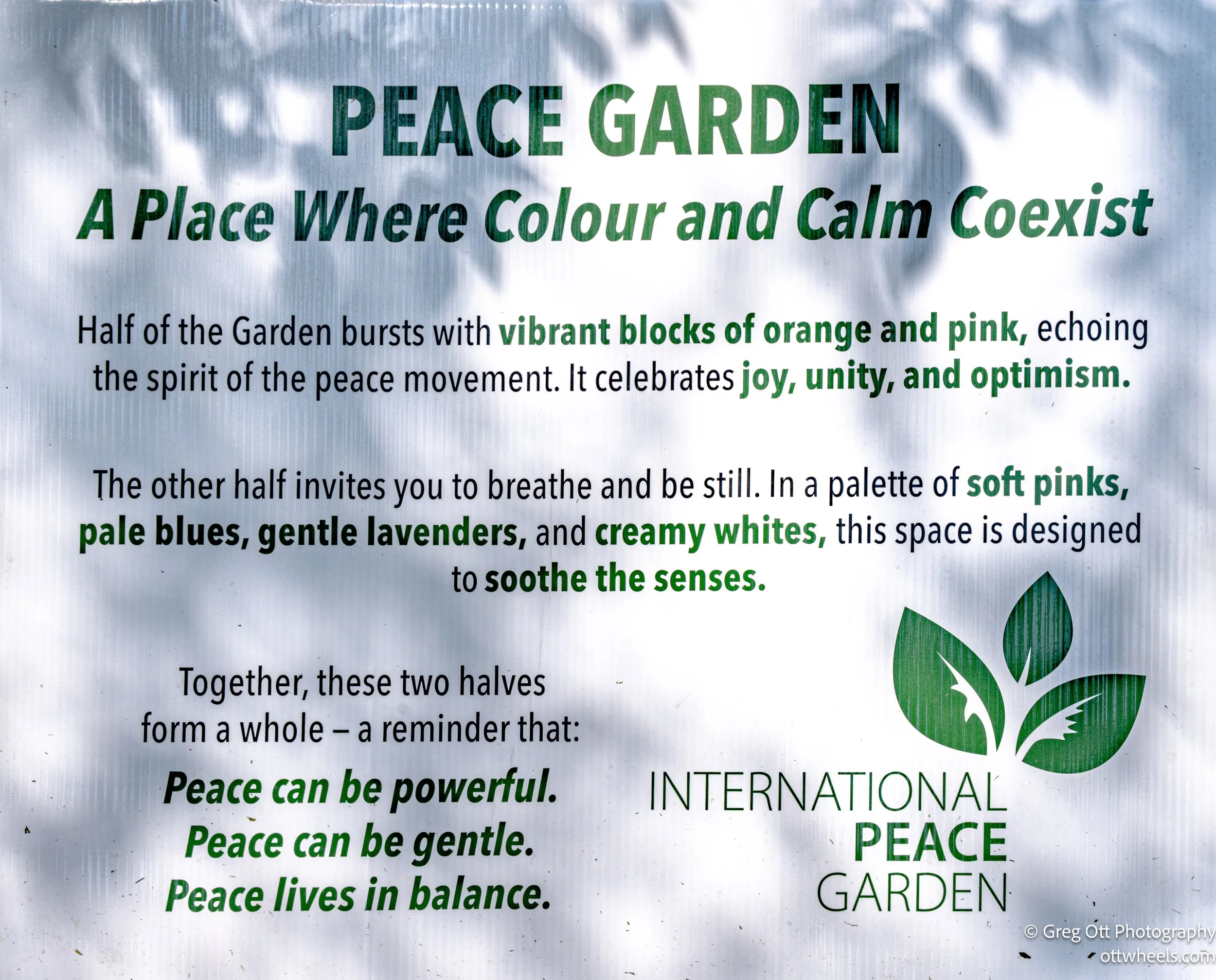

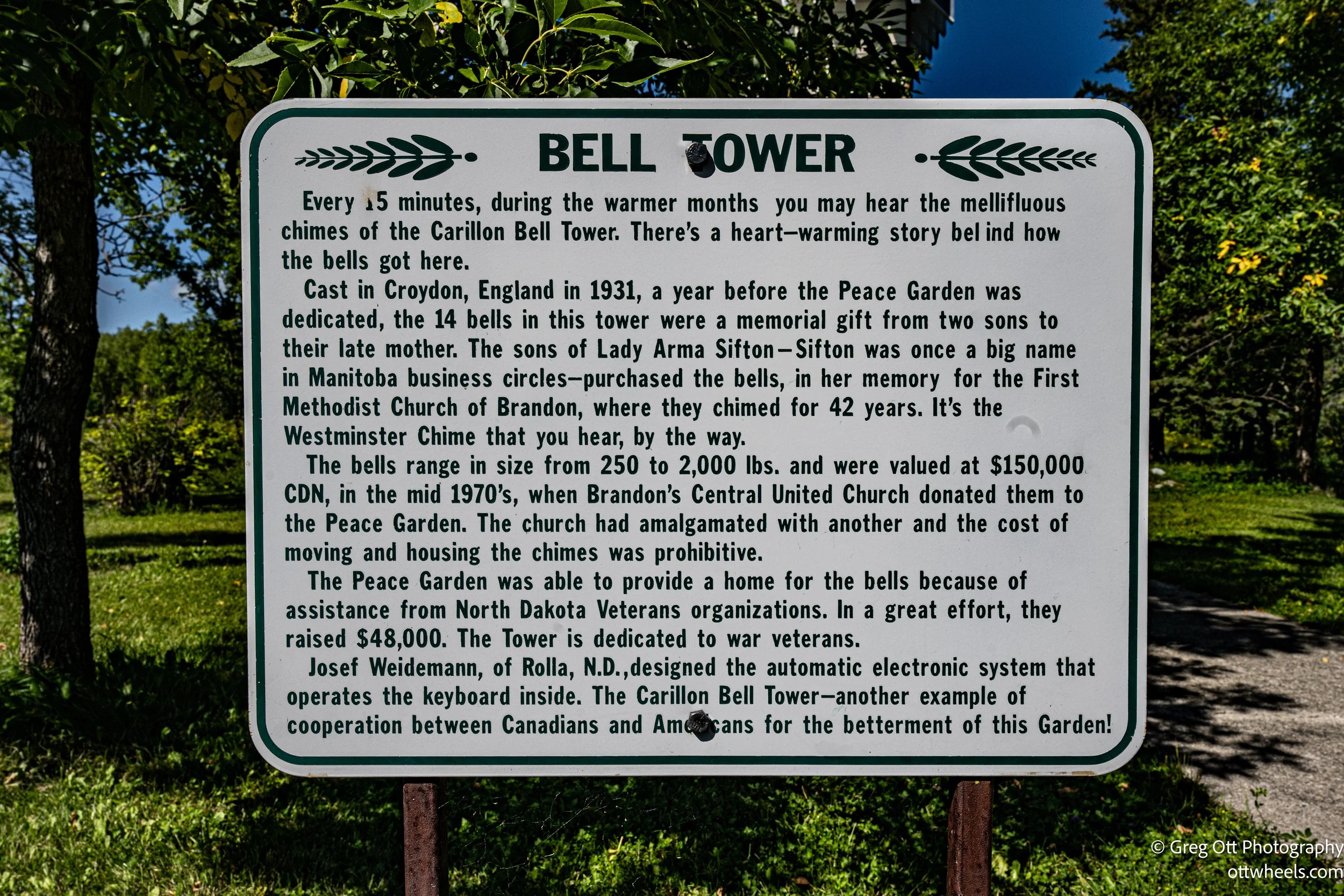

The idea for the International Peace Garden took shape in the late 1920s, during a time when the wounds of World War I were still fresh. Civic leaders from both sides of the border wanted a symbol of lasting friendship between the United States and Canada. They chose this site, straddling the boundary line between North Dakota and Manitoba, because of its location—remote, unclaimed by industry, and resting right on the 49th parallel. In 1932, with thousands gathered for the dedication, the Garden was declared a living monument to peace. Over the decades, new features were added: the Peace Chapel, the Carillon Bell Tower, memorials, and thousands of flowerbeds that change each season.

Exploring the Grounds

The layout of the Peace Garden is unique. On the outer edges, there’s an American loop and a Canadian loop, and between the two is a three mile walking loop that ties everything together. You can drive to most of the main points of interest, park, and then walk a short distance. I parked near the entrance and spent four hours wandering the grounds. I had lunch at the café and took a lot of photos. The food was fine, but the service was painfully slow. The brewed coffee was another story—burnt, sitting for hours on the burner, and no cream available. It was so bad I tossed the cup after two sips, doing my best to “dispose of it peacefully.”

The Cacti and Succulent Conservatory

One of the most striking parts of the grounds is the Cacti and Succulent Conservatory, one of the largest collections of its kind in North America. Stepping inside feels almost surreal, especially when you remember you’re standing on the border of two northern countries where winters are brutal. The greenhouse is filled with towering cacti, sprawling succulents, and desert plants from all over the world. Some of them look almost alien, with twisted arms and jagged edges. It was by far my favorite part of the International Peace Garden, partly because it was so unexpected in this setting.

The 9/11 Memorial

Walking the grounds is a lesson in contrasts. There are formal gardens laid out in geometric patterns, vast flowerbeds forming the flags of both nations, ponds and fountains, and quiet wooded areas. You can wander into the 9/11 Memorial, where twisted steel beams from the World Trade Center rise as a stark reminder of the cost of violence and the fragility of peace. Standing in front of it, surrounded by trees and silence, it hits differently than seeing it in a city. It was deeply moving.

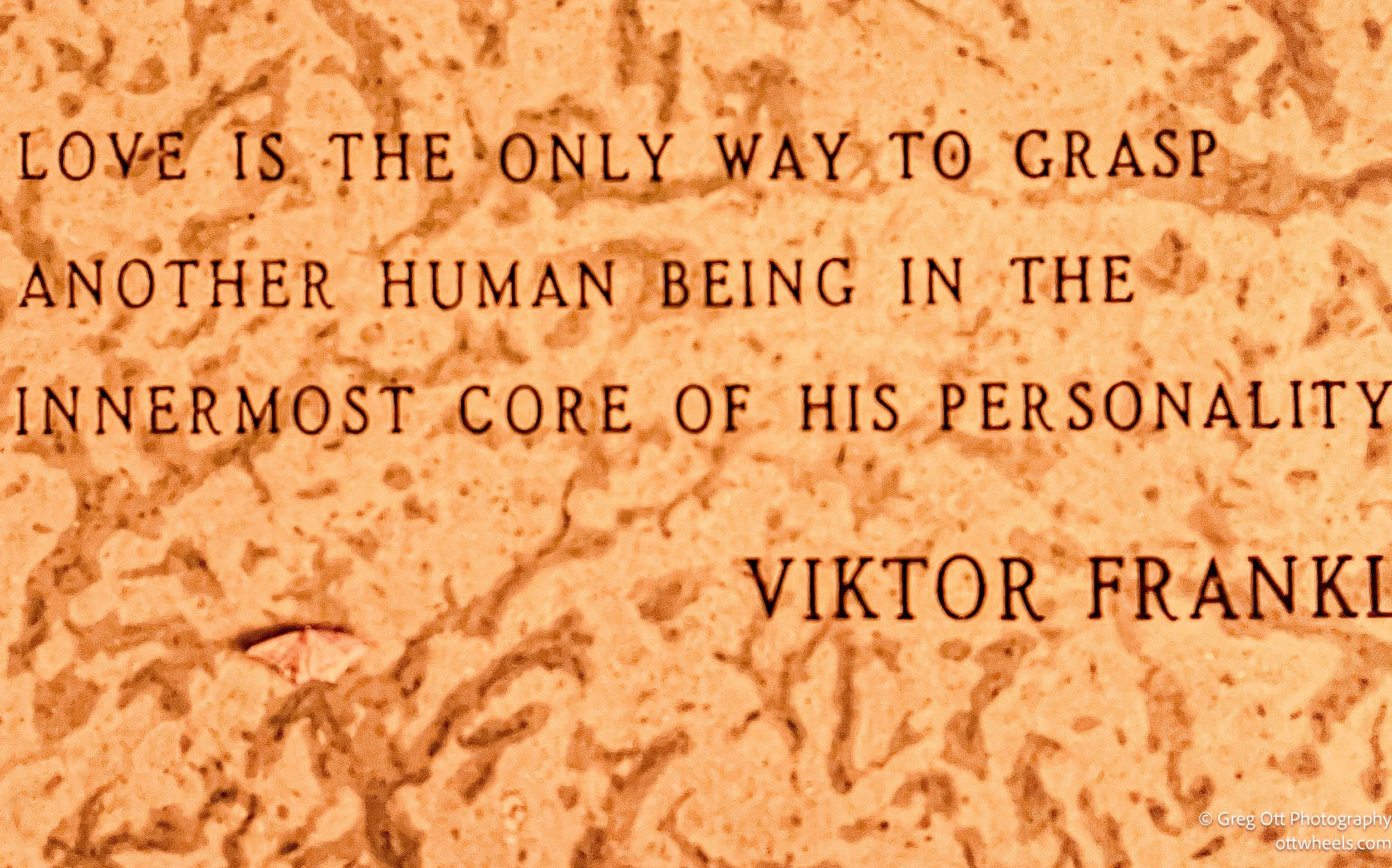

The Peace Chapel

The Peace Chapel is another place that encourages reflection. Built in 1968, its walls are inscribed with dozens of quotes about peace, freedom, and humanity, etched into fossil-studded limestone panels. As I walked through, I stopped at a quote from Viktor Frankl: “Love is the only way to grasp another human being in the innermost core of his personality.” At that moment, a butterfly fluttered down and landed on the words. It felt almost staged, the kind of thing you don’t forget. Other quotes caught my attention too, like one from John F. Kennedy: “Mankind must put an end to war or war will put an end to mankind.” The chapel is small, but powerful.

I walked the full length of the Formal Garden, a wide corridor of flowers and stonework stretching directly across the U.S.–Canada border. Every step carried the symmetry of the design, a living reminder that this place was built to honor peace between two nations.

The Sunken Garden Fountain Pool sat at the center, water spilling gently over its edges. Its constant motion drew the eye, a still point in the middle of the carefully tended gardens.

Further along stood The Promise of Peace sculpture, a striking piece that seemed to anchor the garden with its message of unity. Surrounded by blossoms, it was a quiet space that invited reflection.

On the way to the chapel a brilliant flower arrangement came into view. One bed carried the stars and stripes of the United States, while the other mirrored it with Canada’s maple leaf. Bright blooms in red, white, and green gave the border itself a softer, more hopeful meaning.

What tied it all together was the stream of water that flowed right along the international line. Its movement was subtle but constant—like the heartbeat of the garden—reminding me that peace, too, is something that must keep flowing to remain alive.

And yes, there were many flowers all around the gardens.

Leaving the Garden

By 4:00, I drove the American loop, stopping briefly near the campgrounds where I was able to fill my water tank. Then I crossed over to the Canadian loop. Walking the grounds gives you the deepest experience, but even driving the loops, the design pushes you to slow down, reflect, and not be in a rush. Finding peace in ourselves, the Gardens remind us, is the first step to finding peace with others.

It was close to 5:00 when I pulled into the American border station. The place was covered in surveillance gear—cameras, sensors, things I didn’t even recognize. Anyone thinking about smuggling would probably think twice. The usual questions came up: had I been to Canada recently? (they already knew the answer was yes, about a week ago). After about ten minutes, I was cleared and back on the road.

Mystical Horizons

My next stop was Mystical Horizons, about 30 minutes away, where I planned to stay the night. I parked in time for what promised to be a spectacular sunset. Around 6:30, a guy waved me over from his camper. His name was Chuck, from Philly, and he noticed my Pennsylvania plates. He works out of his van and was heading back east after spending time in Montana—where he had a new transmission installed and, from the sound of it, explored a lot of the state. We ended up talking for over an hour, trading road stories. At one point the setting sun poured straight into his van, painting the inside with gold, and I grabbed my camera.

I stayed, waiting for the sky to darken. I wanted to try for some Milky Way shots, even if it meant I wasn’t going to get much sleep.