Antelope Canyon - Page, AZ

I woke in the Walmart parking lot in Page, Arizona, and ran inside to grab a few things I’d forgotten the night before. As far as Walmart overnights go, this one ranks in my top five — quiet, level, and restful. I slept well. That mattered because I needed to be at Ken’s Tours, about fifteen minutes away, for my visit to Antelope Canyon.

I had booked the 10:30 a.m. Deluxe Tour of Lower Antelope Canyon. I arrived early, around 8:30, and signed in at the desk. They told me to return at 10:00 for orientation. The Deluxe Tour limits the group to six people and includes more than just the canyon walk: a short film, an introduction to Navajo culture, a visit to a traditional Navajo-style dwelling, lunch, and a few small souvenirs — a booklet, a dreamcatcher keychain, and a postcard.

The tour begins behind the main building. When we stepped outside, my first thought was: where exactly is the canyon? From the parking area, nothing looks dramatic. We walked about a tenth of a mile downhill over slick, weathered sandstone until we reached a checkpoint where a woman sat with a clipboard. Our guide, Ben, told her “six.” She verified the count and marked it on a chart. That headcount system is constant — groups are tracked going in and coming out.

We were standing on layered Navajo sandstone. Ben explained that each visible layer represents roughly 100 years of deposition and erosion cycles. Based on rainfall patterns in this region, it takes approximately 1,000 years to erode a single inch of rock. Standing there, looking at striations carved by time and flash floods, the scale shifts. What looks smooth and sculpted was shaped over thousands upon thousands of years.

Before descending, Ben gave us strict instructions: no photos on the stairs. People have lost their balance, dropped cameras, and knocked into others below. The entry is narrow and steep — metal staircases bolted into the rock guide you down into the slot.

He also spoke about flash floods. The most tragic incident occurred in 1997, when eleven tourists were killed by a sudden flood in Lower Antelope Canyon. A thunderstorm miles away sent a wall of water roaring through the narrow passage with almost no warning. Since then, safety protocols have changed significantly. The Navajo Nation monitors weather patterns constantly. Tours are canceled at the slightest risk. There are spotters and communication systems in place, and headcounts are strictly enforced. The canyon is closed immediately if conditions shift. It was a sobering reminder that this beauty exists because of water — and water is unpredictable here.

We descended into the canyon on a series of metal staircases. At the bottom, Ben gave us a brief history of exploration in Antelope Canyon. For generations, Navajo shepherds knew about the slot. Early visitors climbed down using hand- and footholds carved into the rock. Later, ropes and wooden ladders were added to make the descent safer. As tourism increased, permanent metal stairs were installed to allow controlled access. Ben joked, “Next time you visit, we’ll have an escalator.”

Once inside, the world changed.

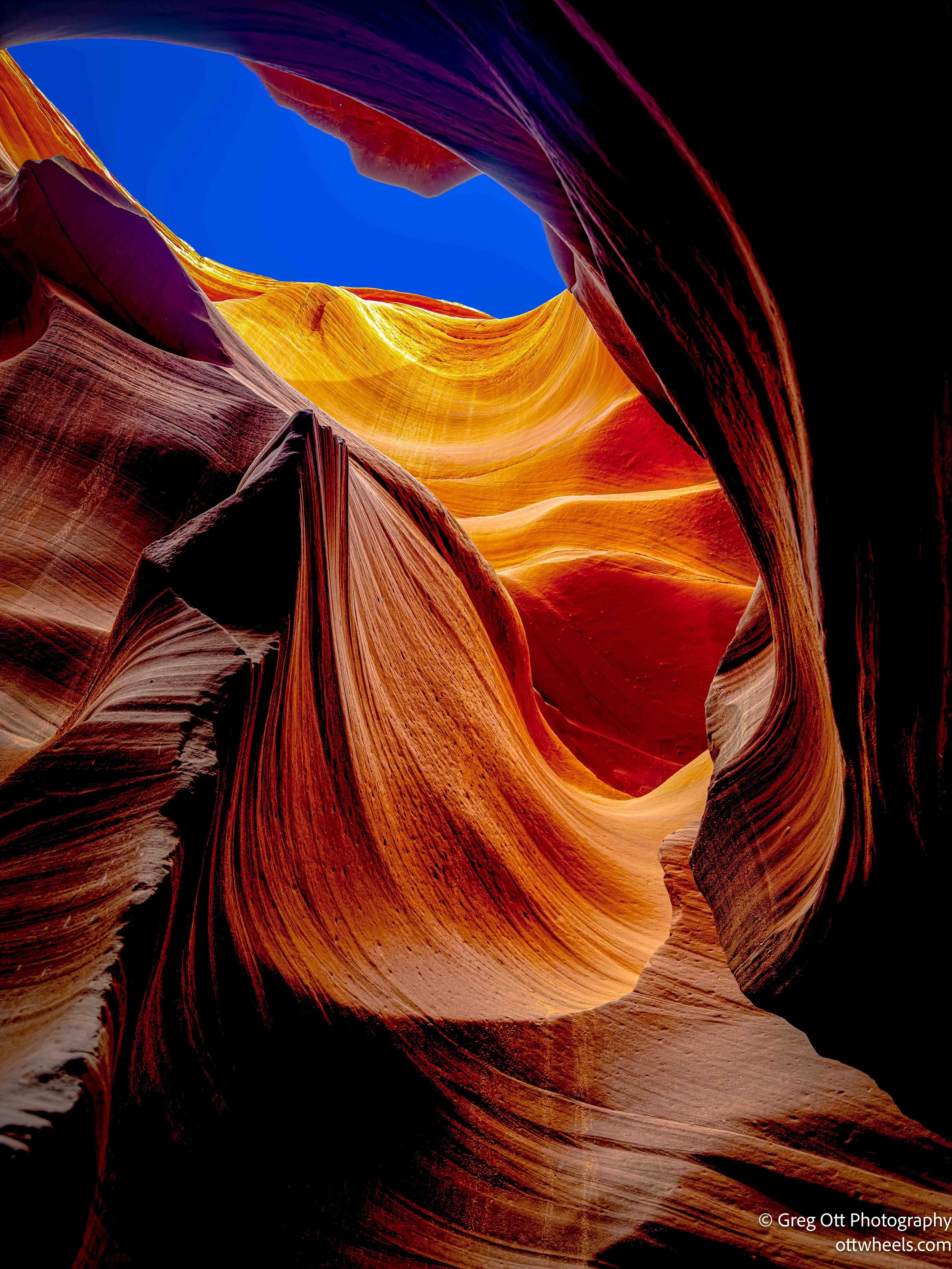

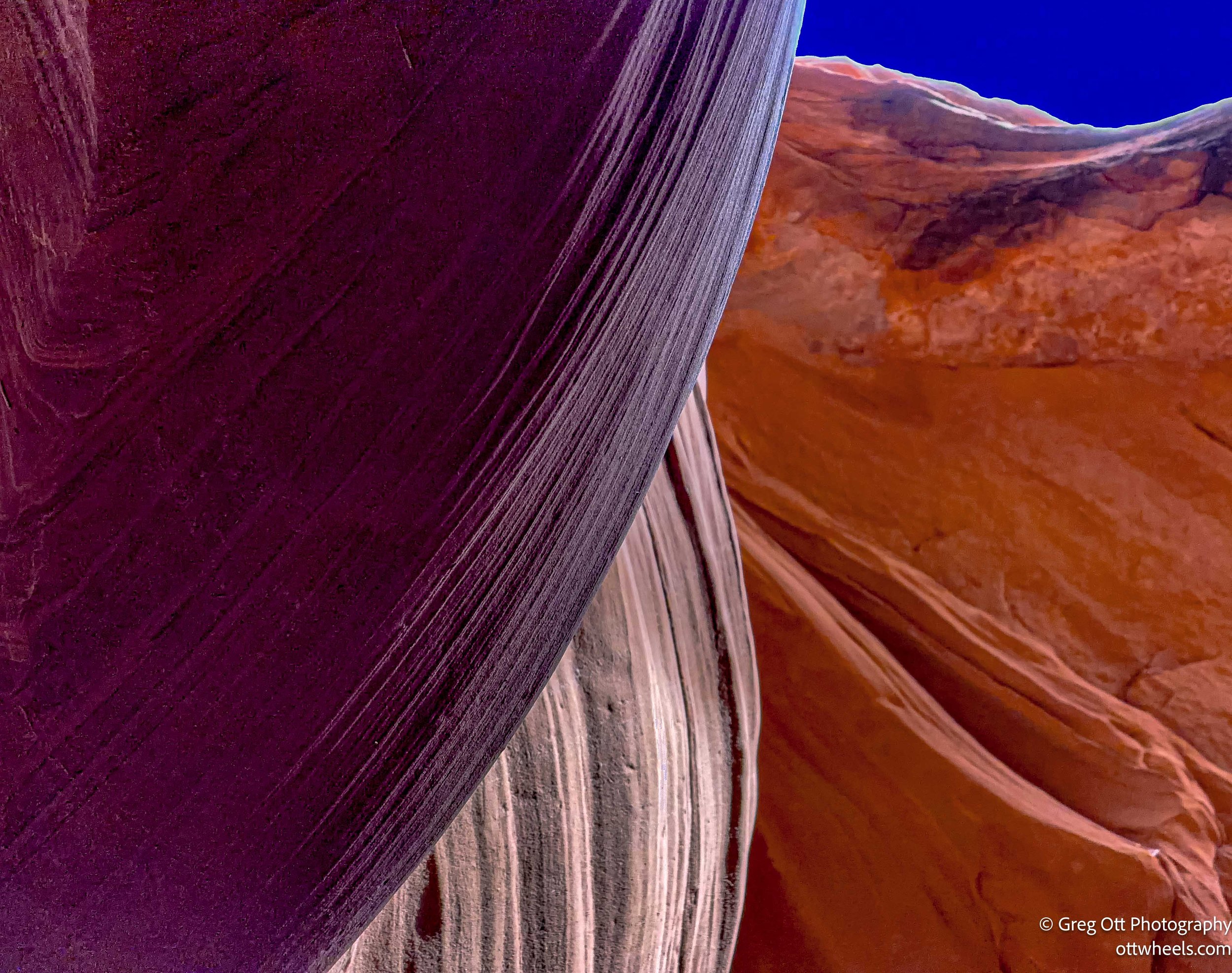

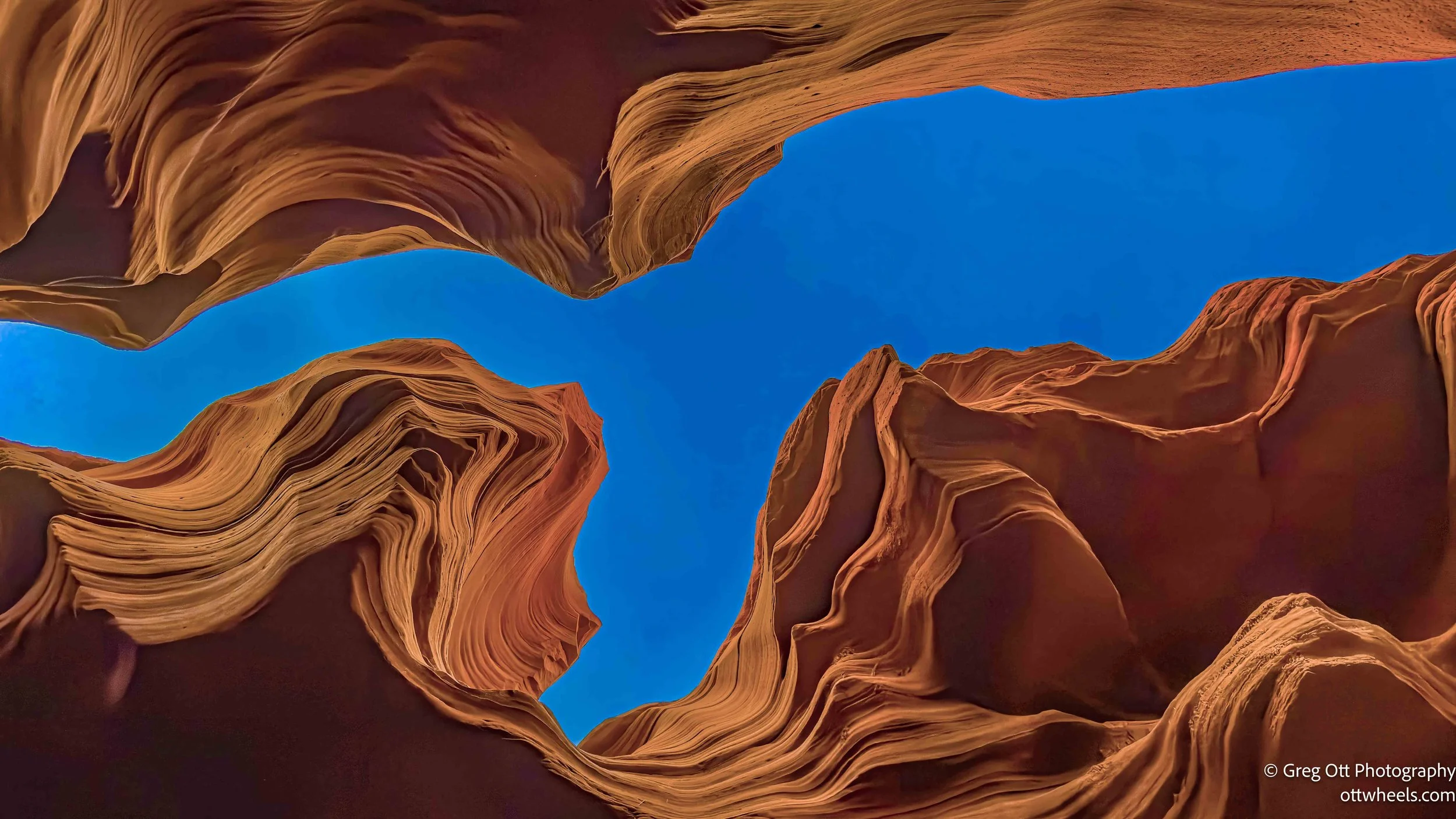

The light narrowed. The temperature cooled. The walls rose in twisting ribbons of orange, red, and violet. The canyon floor is sandy and level in sections, but the walls undulate in curves that feel almost fluid. This was not a hike in the traditional sense — it was a slow progression through sculpted stone.

The walk through the canyon lasted about an hour. There are two authorized operators in Lower Antelope Canyon — Ken’s Tours and Dixie Ellis’ company — and tours are staggered in fifteen-minute intervals. Even with staggered timing, you are not alone in the canyon. Groups pause, wait, and move through carefully choreographed sections. At certain iconic bends, guides coordinate so each group can have a few moments to photograph without interruption.

Ben pointed out formations people associate with animals — a dragon’s head, an eagle, a face in profile. I stayed back often to focus on photography and missed some of those interpretations. Periodically, Ben would stop and ask if anyone wanted a photo. He knew exactly where to stand us and how to angle the camera for the best effect.

Antelope Canyon became globally famous not just through photography magazines, but through technology. Over the years, images of the canyon have appeared as screen savers and wallpapers on Windows, Apple, and Samsung devices. Ben mentioned that Apple periodically updates its Antelope Canyon imagery, returning to capture fresh versions of the light beams and curves. Those wallpapers introduced millions of people to a place they had never heard of. Many travelers — myself included — saw the canyon first on a screen long before standing inside it.

We were only allowed to bring a camera with one lens, a phone, and water on the tour. I chose the 14–24mm to capture the wider angles. In a slot canyon where space is tight and the walls rise straight up, that extra width makes all the difference.

Light is everything here. Around mid-morning, beams filter down from narrow openings overhead, especially in Upper Antelope Canyon, but even in Lower, shafts of light slip through, bouncing off sandstone walls. The reflected light softens shadows and creates gradients that look almost painted. The colors shift depending on angle — deep crimson in one direction, pale peach in another. I found myself adjusting exposure constantly, careful not to blow highlights where sunlight met shadow.

The canyon narrows in places to just a few feet wide. In other sections it opens slightly, revealing vertical slices of sky. The sandstone feels almost alive — shaped by centuries of flash flooding that carved flowing, wave-like textures into the rock. Every turn presents a new abstract composition. It is easy to understand why photographers return again and again.

We eventually reached the exit — a narrow opening barely three feet wide. We climbed a final staircase and emerged back into open air. Ben walked over to a man seated in a chair, gave his name and confirmed “six.” Again, the count. No one left behind.

Just beyond the exit, we stopped to look at what appeared to be dinosaur footprints embedded in the stone — reportedly raptor tracks from millions of years ago. Ben explained that fossil evidence is scattered throughout Navajo lands, though many sites are protected and not publicly accessible. Standing there, you move from thinking in thousands of years to thinking in millions.

We stopped at a replica Navajo home, where Ben explained the Navajo family structure and clan system. Marriage, he said, is guided by strict clan relationships — you cannot marry within your own clan, and lineage is traced through the mother. He also described what it was like growing up sleeping on a rug on the floor in a similar home, giving the history a personal connection rather than just a cultural overview.

The tour concluded back inside at the restaurant area. Our lunch was waiting for us — a Navajo-inspired meal along with traditional Navajo tea. Common versions include Navajo black tea made from locally gathered plants such as Cota (Thelesperma) or greenthread tea, sometimes lightly sweetened. It has an earthy, mild flavor. Simple and fitting after a morning in the canyon.

I stopped in the gift shop and looked carefully at the prints for sale. Some were excellent. I quietly hoped my images would measure up. The light had been very good — soft but directional — and I felt confident I had captured something worthwhile.

I left around 1:30 p.m. and headed south toward Sedona, Arizona. High winds pushed against the van along stretches of open highway. I pulled over several times, partly for gas, partly just to reset. I had shipped a few items to Whole Foods in Sedona and stopped to pick them up, along with a handful of groceries that are hard to find elsewhere.

Just outside town, I found a dispersed camping area around 6 p.m. About ten other campers were already scattered across the open land. I kept dinner simple. The wind continued, rocking the van gently.

Then I settled in to work on the photos.