Falls of Hills Creek & Cranberry Glades Botanical Area

I stayed at Twin Falls Resort State Park again. Before leaving, I filled the water tank, then drove north to a Starbucks just off Highway 19—a big, new stopover complex full of trucks, commuters, and travelers like me catching a few minutes of Wi-Fi and caffeine before heading deeper into the hills. Over coffee, I planned my route to Falls of Hills Creek.

The gas tank was below half, so I topped it off. Each pump had its own air station, though strangely without a way to measure pressure. I pulled out my battery-powered pump, set the PSI, and checked each tire. The front two were down by two pounds, the back two by four. I was surprised how little they’d dropped in just the months since I last checked even with hot and cool nights and mountain driving.

Falls of Hills Creek

It was a two-and-a-half-hour drive to Falls of Hills Creek, winding through the forested spine of West Virginia. The route followed a series of narrow roads that cut through the Monongahela National Forest—occasional pull-offs revealing deep valleys and long ridgelines brushed in autumn color.

Small Town West Virginia

Falls of Hills Creek is one of the more remarkable spots in the Monongahela National Forest. Three separate waterfalls drop in sequence through a steep gorge: the upper, middle, and lower falls, together falling nearly 300 feet. The first section is easy, paved and accessible, but the trail quickly becomes a staircase of roots and wooden steps, winding down through damp forest and moss-covered stone. Wooden bridges cross the creek several times, and you can hear the water long before you see it. The smell of wet leaves and hemlock fills the air, and mist hangs low over the gorge.

The lower falls, the tallest of the three, is worth every step of the climb back. It drops nearly 65 feet into a narrow amphitheater of stone, where the roar of the water echoes off the walls and drowns out every other sound. I lingered there for a while, photographing the curtain of water and watching it shift from silver to white as clouds moved across the sun. The hike back up felt longer than expected—steep, all uphill—but it was worth it.

On the way down, I passed only two other hikers, a couple who seemed oddly reserved. I said hello; she said nothing, and he gave a quick nod before looking away. They spoke to each other in hushed tones, almost whispering. I don’t think they were being secretive—it just seemed to be how they communicated. I’d see them twice more as I stopped at each waterfall. We never exchanged another word.

Cranberry Glades

Back on the road, I noticed a sign for a Monongahela Nature Center—unusual for a national forest—so I stopped. Of course it was closed this time of year. A woman sat alone at a picnic table in the nearby pavilion, watching me as I pulled in. I waved, but she looked away, uninterested.

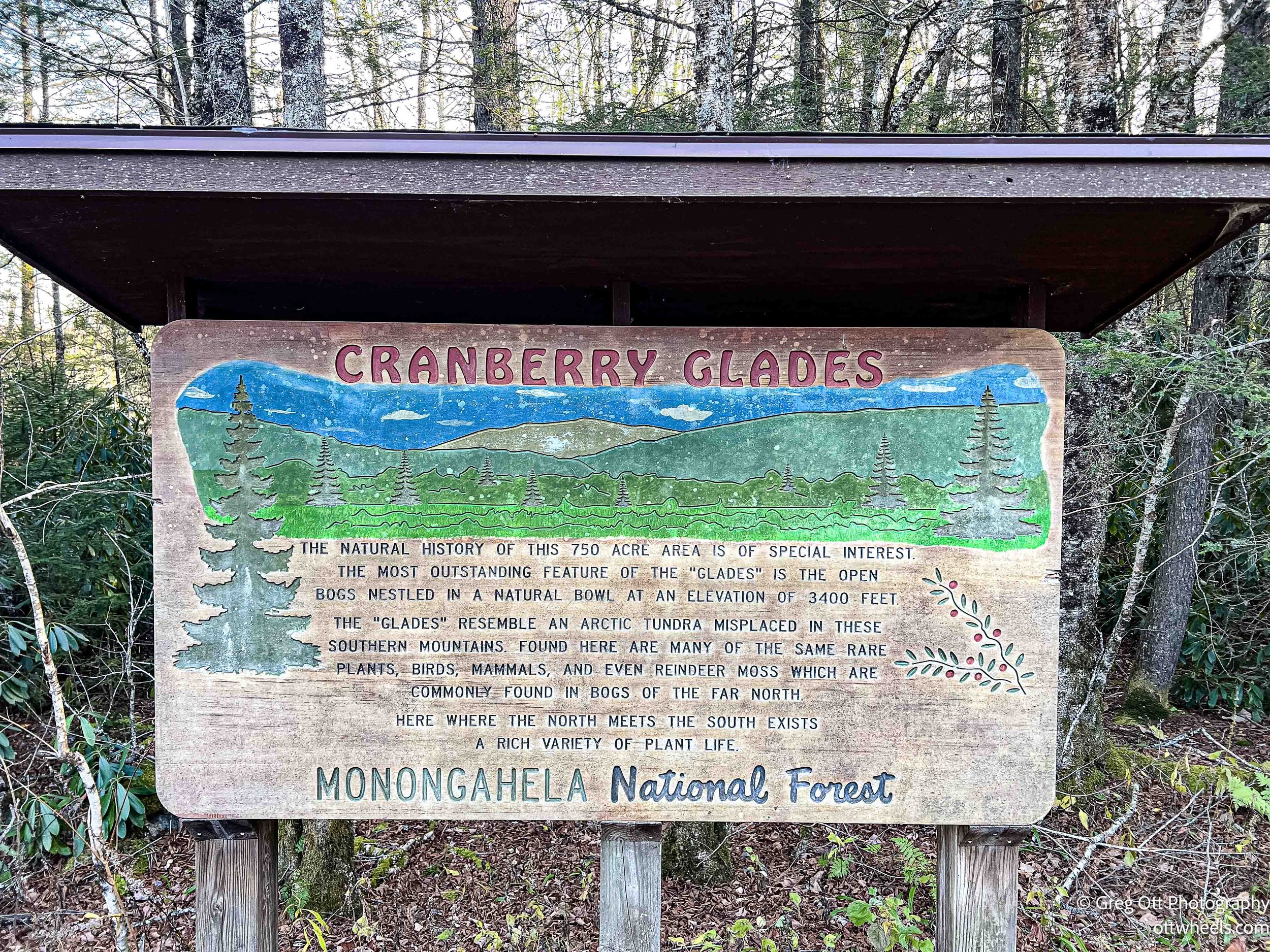

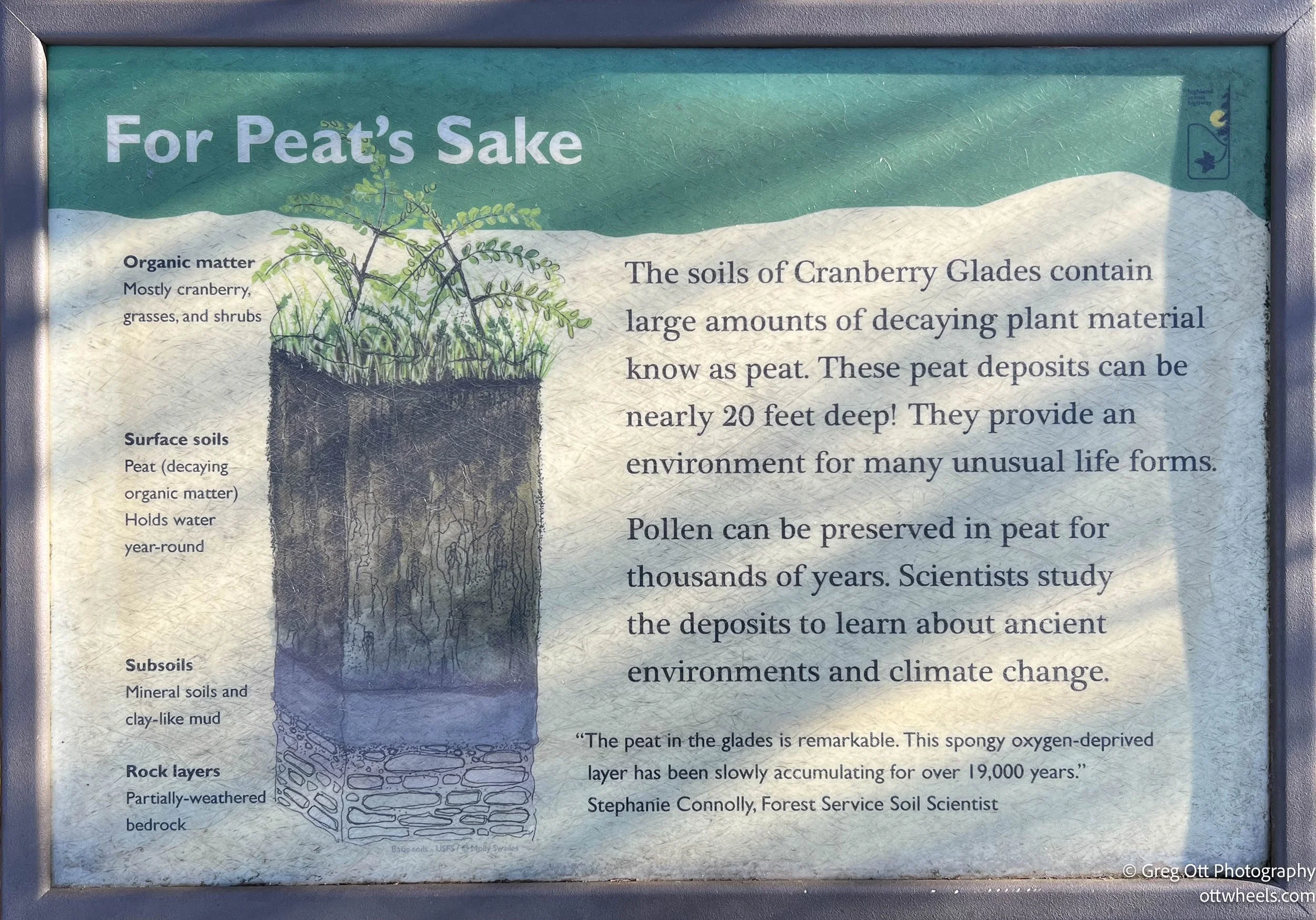

Cranberry Glades is one of the most unusual landscapes in West Virginia—a pocket of ancient tundra left behind when the glaciers retreated more than ten thousand years ago. The area looks like a simple mountain meadow, but it’s actually a cluster of high-elevation bogs, layered with up to twenty feet of peat moss. Peat moss forms when plants die and decompose so slowly in water-saturated, oxygen-poor soil that their remains pile up year after year. The result is a deep, spongy mat that acts like a natural sponge, holding water and preserving centuries of plant material. Because oxygen can’t penetrate the soil, trees struggle to grow. What thrives instead are acid-loving plants—cranberries, sedges, pitcher plants, and sphagnum moss—that resemble the flora found much farther north in Canada or Alaska.

The glades sit in a natural bowl, and every drop of water that enters moves sluggishly through the peat before trickling into the Cranberry River, making it one of the cleanest waterways in the region. Walking the boardwalk loop feels like stepping into a living museum of prehistoric Appalachia. The air is cooler and heavier with moisture, and the landscape has a quiet, primeval feel—as if it has changed little since mastodons grazed in the valleys below. Scientists study the peat layers here to read the history of past climates, pollen shifts, and plant evolution. It’s a small, self-contained world—fragile, ancient, and quietly defiant against the faster, louder rhythms of the modern forest that surrounds it.

At the Nature Center, a park policeman pulled in. I asked if he had a map or brochure for the area. He did. He got out, handed me one, and asked if I was from Pennsylvania—he’d spotted the plates on the van. We ended up talking for a while about the park system, the government shutdown, how closures ripple through small mountain towns, and how new tech might help with park management. His patrol truck was a rolling command center, impressive in its setup. When I asked about overnight parking, he said, “You can park almost anywhere, but you’ll be most comfortable on Route 150.” He was right—the road has cutout turnoffs, paved and level, without the long dirt roads of many national forests that can rattle everything inside the van.

I drove to Cranberry Glades, a high-elevation bog surrounded by spruce and fir. The trail is a three-quarter-mile boardwalk raised just a few inches above the bog. The air was warm for the time of day and season, and the place was almost completely still—the only sounds were a few birds and the faint trickle of water beneath the boards. I walked slowly, reading the plaques that explained the area’s history, ecology, and the plants and animals that live there. It was very different from a walk in the forest. I made a mental note to come back when the cranberry plants are in season.

The Cyclist

I’d brought the macro lens and was working on a series of close-ups—seed pods, lichens, textures of decaying leaves. I was crouched low over the boardwalk photographing an odd, tufted seed head when I heard a rhythmic click-clack behind me. Before I could stand, a big guy on a mountain bike rolled to a stop.

In a booming, cheerful voice that shattered the silence, he said, “Oh! Sorry—just need to get by!” He spoke fast, like every word was in a hurry. He glanced at the sky, then back at me. “What’re you photographing?”

I pointed to the seed pod. “I’m not sure what it is.”

“Oh, that’s Clematis! Yeah, pretty sure. It’s a vine,” he announced—still shouting as though I were fifty feet away. He had the energy of a man who had already consumed a few too many espressos—or perhaps was simply powered by his own enthusiasm. “You doing macro work?” he asked.

“Mostly landscapes and some macro,” I said.

“I love macro!” he practically shouted. “It’s a lot of work, though! I do photography, too!” He beamed, fidgeted with his handlebars, then declared, “Well, I need to finish my ride and have a beer. Bought some new craft brews!”

And just like that, he was gone—tires crunching on gravel, his voice fading into the woods. The quiet afterward was so complete it felt amplified, like the forest itself was catching its breath.

Evening on Route 150

Route 150 was just a few miles away. I turned onto it as the day slid into golden hour. The forest lit up—the trees glowing orange and red, the low light bouncing through the valleys. I stopped at a pull-off to take it in, the hills ablaze with color.

There were dozens of scenic turnouts along the road. I chose one that curved slightly into the forest, driving in about fifty feet before stopping for the night. The wind picked up, and now and then a gust rocked the van, even sheltered under the trees. Weather Underground showed gusts around forty miles per hour. I was glad I wasn’t still driving.

I cooked a simple dinner: chicken with a side of pasta and tomato sauce. As I ate, the last light drained from the sky and the forest settled back into stillness. Then began the hours of processing the photographs.