Canyonlands National Park

I spent two days and nights in Canyonlands National Park, and in many ways I found it more compelling than Arches across the valley. The views here feel larger and less immediate. Everything stretches farther, drops deeper, and asks more patience. It isn’t a park that tries to impress you right away. You have to slow down, wait for the weather, and let it reveal itself.

Day 1: January 23rd: I woke just outside the park on BLM land and drove in around eight, only to realize the visitor center didn’t open until nine. I made breakfast in the parking lot, had coffee, and took care of a few online things until mid-morning. When the doors finally opened, I got my stamp for the NPS Passport book, talked briefly with a ranger, and picked up a park map. As I stepped back outside, light snow was falling and the clouds had dropped noticeably. It wasn’t a great sign for canyon views or hiking.

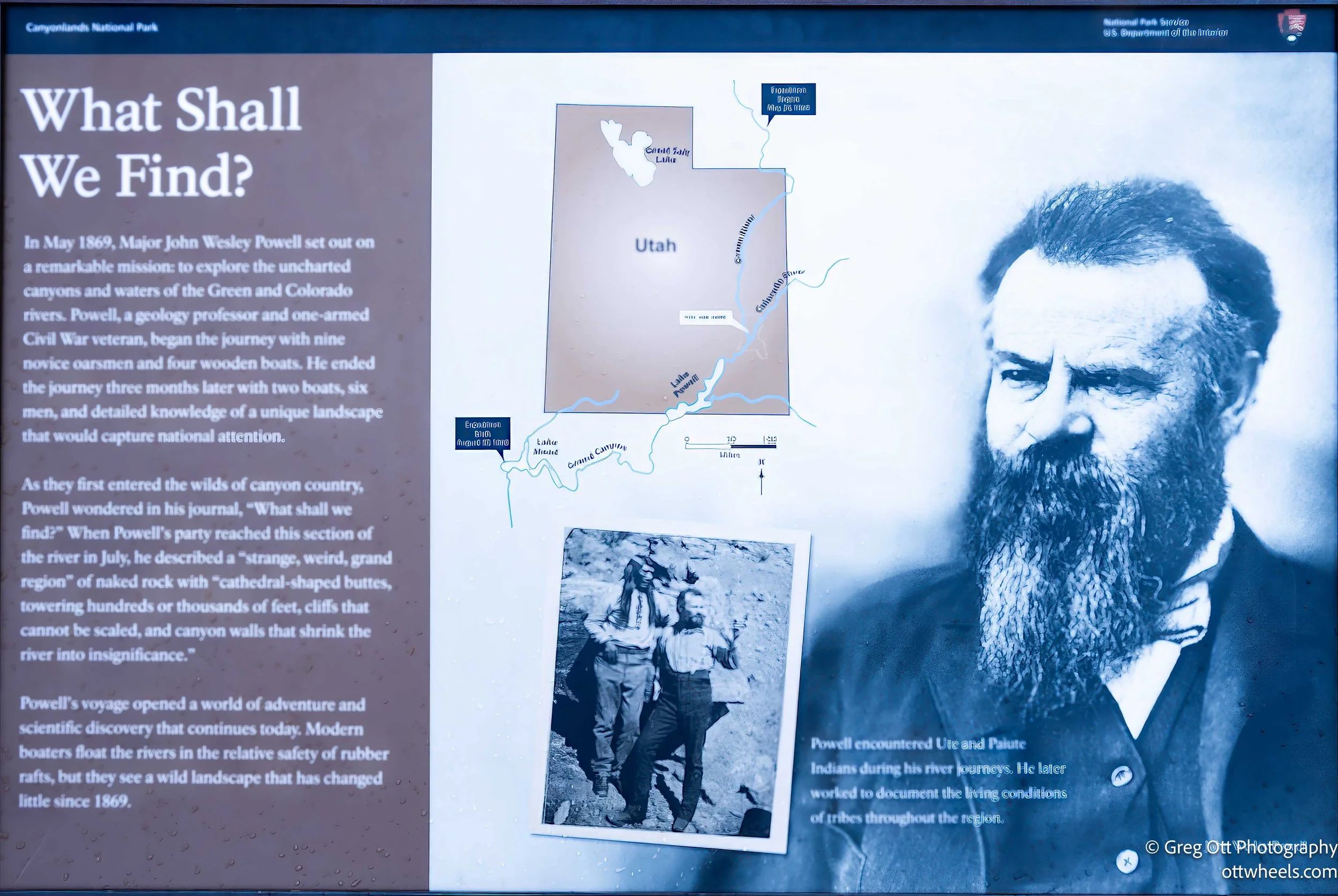

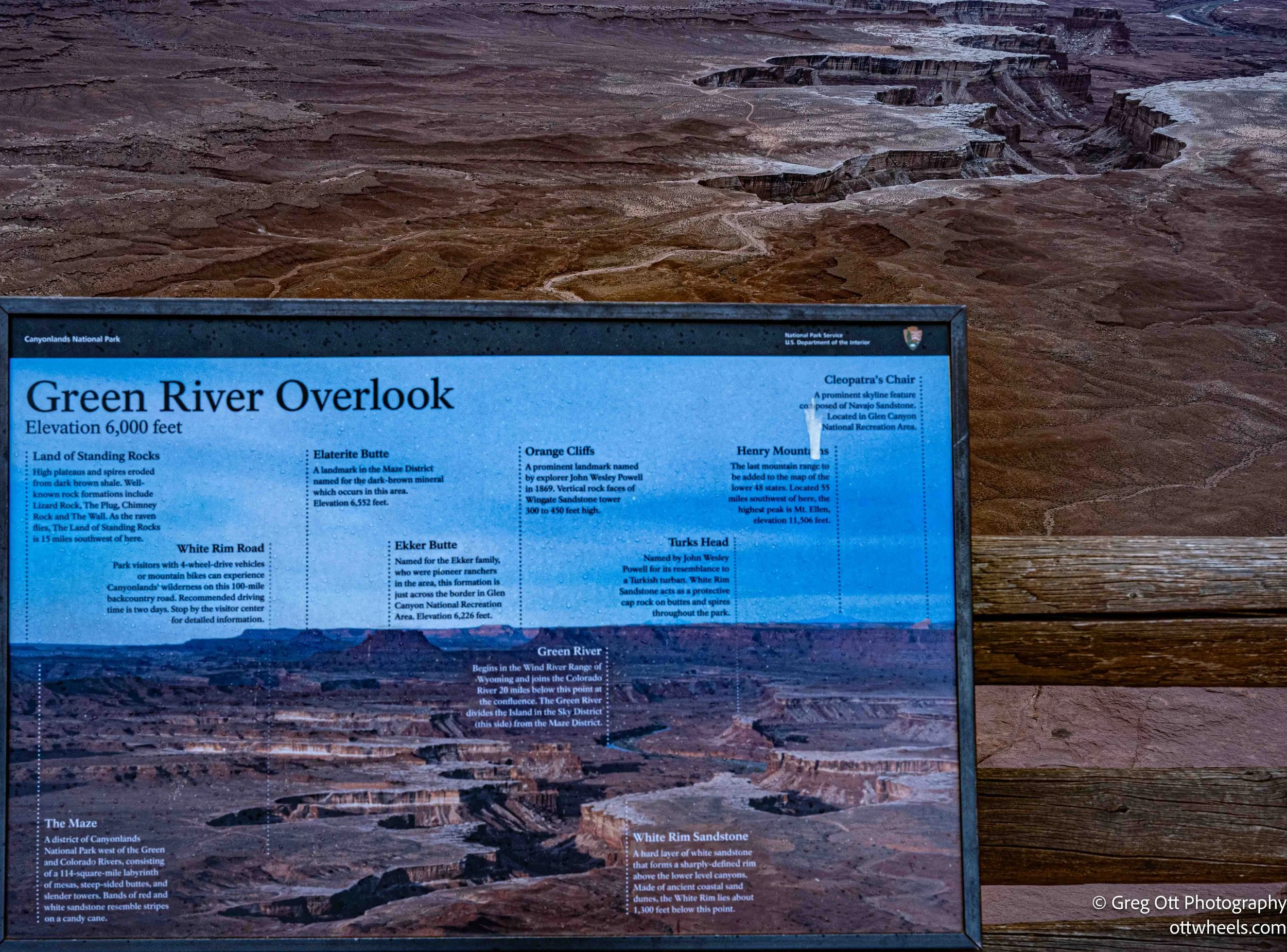

I drove out to the Green River Overlook and spent some time reading about the river in the distance. The Green River flows all the way from Wyoming and eventually meets the Colorado River inside the park. Standing there, it was easy to understand why this area mattered so much to early exploration. In the late 1860s, John Wesley Powell led the first documented expeditions through the Green and Colorado Rivers, mapping much of this region for the first time. Powell, a one-armed Civil War veteran, geologist, and scientist, didn’t just chart waterways—he fundamentally changed how the American West was understood. He recognized that aridity, not distance, would define settlement here, and he argued that water should determine land use. His work laid the foundation for modern western geography, and Lake Powell bears his name in recognition of the impact of those expeditions. Standing above the river he once navigated by wooden boat made the scale and difficulty of that work feel very real.

The overlook itself was overwhelming. First there was the sheer drop straight down from where I stood. Beyond that, a broad plateau stretched endlessly into the distance. Then the land fell away again, plunging into a maze of canyons carved over unimaginable time. Snow-capped mountains lined the horizon beyond the plateau, adding another layer of depth. After taking a few photographs, I found myself just standing there, watching the clouds continue to lower and move steadily in my direction.

With visibility worsening, I turned back and took a campsite at the Green River Overlook campground. At seven dollars and fifty cents per night, staying two nights was an easy decision. There were no reservations through Recreation.gov—fourteen sites, first come, first served. That night there were four RVs, three campervans, and a small sixteen-foot trailer. One campervan, a Mercedes Sprinter, had French license plates. It was so quiet I never heard anyone arrive or leave. Snow continued into the evening, softening everything further.

After making soup for lunch, I hoped to get in a short hike. I drove toward the area near Whale Rock and parked for about fifteen minutes, but the fog was rolling in fast and people were packing up. I didn’t want to risk getting stuck on a trail with visibility dropping, so I headed back to the campground instead.

Later, I tried again and drove out toward Upheaval Dome, thinking I might do a short hike near Whale Rock or one of the trails leading through Upheaval Canyon. It was about a seven-mile drive, and by the time I arrived, the snow was falling heavier and visibility had dropped even more. There was no cell service—just an SOS indicator—and without knowing the trails, it didn’t feel smart to push farther. I turned back, knowing this would be a place to return to another day, under better conditions.

Day 2 January 24th: Grand View Point Overlook

I woke up in the park at the Green River Overlook campsite. It had snowed overnight—less than a 1/4 inch—but enough to soften the edges of everything. The sky was overcast and slightly foggy, with the sun trying, without much success, to break through. No one in the campground was moving yet, and it felt too early even for day visitors. I sat at the computer and waited, watching the light shift slowly. I wanted this to be a camera day, but only if the conditions earned it.

By noon the fog finally lifted, and I drove towards to Grand View Point Overlook. I stopped many time to go explore the pull offs.

When I reached Grand View Point Overlook, there wasn’t a single car when I arrived, which felt strange given how popular this overlook usually is. I parked the van close to the edge, just off the pavement, and stepped out into a stillness that felt deliberate, almost protected. The canyon opened up in layers, the far distances still subdued, the closer formations beginning to separate from one another.

I started by capturing the big view. Grand View Point doesn’t ease you into it—you’re immediately standing above an immense drop, looking out over miles of carved stone. Clouds drifted in and out, changing the contrast every few minutes. I’d take a few frames, wait, then take a few more as the light shifted. With no one else around, it was easy to slow down and let the scene dictate the pace.

After a while, I shifted focus completely and moved into the smaller world at my feet. I spent time photographing plants—small cacti and young yucca—each holding pockets of snow deep inside their structure. This wasn’t casual macro work. I was taking close to one hundred images of a single subject, carefully adjusting focus with the intention of merging them later into a single, ultra-detailed frame. The goal was to reveal what you normally never see: the interior spaces of these plants, layered, precise, and briefly transformed by snow.

This type of photography I find extremely difficult and seldom have success, but when it works it is spectacular. Nothing about it is fast, and nothing can be rushed. The plants weren’t going anywhere, but the snow was temporary, and the light kept changing. It felt like working inside a narrow window that might never open again in quite the same way. I wasn’t as successful as I had hoped, but lessons were learned.

What stood out through all of it was the silence. According to the National Park Service, ambient noise levels here are among the lowest in the country, and standing alone at the overlook, it felt absolutely true. Any sound that registered came from natural sources—wind, birds, maybe a distant hiker far below. The park treats silence as a resource, and being there, it was obvious why. It wasn’t just peaceful; it was a deep relaxing experience. As I stood there, the light continued to change.

Later in the afternoon, I spent a couple of hours slowly driving through the park, stopping whenever the light or landscape suggested something worth pulling over for. At one point, I pulled over, made an espresso and pulled the images of the camera. As the sun dropped lower, shadows stretched across the canyon and details that were invisible at midday began to show themselves.

Around six o’clock, I returned to Grand View Point for sunset. From that angle and that light, the canyon below took on a shape I hadn’t fully registered earlier—a massive form that looked like a giant chicken footprint pressed into the earth, the long “toes” of the Needles district reaching out into shadow. The sun broke through just enough to light the rock from the side, and the whole scene settled into a quiet, deliberate ending. It felt less like a conclusion and more like the landscape exhaling. The sunshine was intense for about 15 minutes, and darkness fell over the area quickly.

I spent another night in the over look campground. The snow had mostly melted and there was only one other camper. I felt grateful to be able to be here in the dead of winter with such calmness.