Great Salt Lake State Park

I left Vegas on the 3rd and drove for about five hours. This was mostly a travel day, heading toward Salt Lake City. I took longer routes instead of the Interstate and ended up in a Bureau of Land Management (BLM) area for the night. It took a while to find a place to stay. I checked four different BLM sites, but there was too much mud, and I didn’t want to risk getting stuck. The spot I finally settled on was about five miles east of I-15. I wasn’t completely alone, but there weren’t many people out here in the middle of Utah at this time of year.

On the 4th, I took the morning slowly—reading with an espresso, then making a late breakfast. The temperature was in the 40s, and I had a few hours of driving ahead of me before reaching Salt Lake City.

Creekstone Energy

I avoided I-15 entirely on my way north. I wanted to see what rural Utah actually looked like, to move through places where there wasn’t much reason to stop. There weren’t many people out here, and the road stayed empty for long stretches in both directions. Clouds hung low over the distant mountains. Corrals stood ready for loading cattle, but there were few animals to be seen.

For miles, nearly every sign referenced “Creekstone Energy,” so I looked up what the project actually was. It turns out the plan is something called the Delta Gigasite—a massive combined data center campus and power-generation hub in Millard County that could become the largest of its kind in the world.

From what I found, the idea is to pair enormous energy capacity—up to ten gigawatts—with data center infrastructure designed to handle large computational workloads. The campus isn’t fully built yet, and details about how much will be dedicated to AI-specific systems aren’t clearly published, but scale is clearly central to how the project is being pitched.

What surprised me is that they’re not just building data halls and stopping there. Creekstone has signed a memorandum to study adding nuclear power to the site’s energy mix, alongside solar, natural gas, and potentially wind or geothermal. Nuclear isn’t a done deal—it’s still under evaluation—but it signals how seriously the developers are thinking about long-term, reliable power at a massive scale.

There’s also industry talk about positioning the site for AI and high-performance computing workloads, which makes sense given current trends. That said, I couldn’t find clear information on how large the AI component would be compared to more general cloud or infrastructure uses.

So what I saw along the roadside wasn’t just hype. A real project is taking shape—huge in scale, tied to a diverse power strategy, and wrapped up in the broader push for energy and compute growth—but many of the details are still being defined as it moves through early construction and funding stages.

Great Salt Lake State Park

I eventually reached Great Salt Lake State Park. Entry was ten dollars, and I spent most of my time in the visitor center.

Great Salt Lake State Park is where the scale problem of the lake finally becomes clear. The visitor center film starts with formation, and it doesn’t ease into it. The lake you see today is a remnant of Lake Bonneville, which once covered much of western Utah. At its high point, Bonneville was more than nine hundred feet deep in places. That depth matters. It wasn’t a shallow basin—it was an inland sea with volume, pressure, and stability.

That history makes the present situation hard to ignore. Today, parts of the Great Salt Lake are sometimes only a few feet deep. Not inches below a healthy level—feet. In some areas, the lake barely qualifies as a lake at all. The film makes a point of showing how dramatic that drop is: from hundreds of feet of water to a shallow, highly exposed surface that rises and falls quickly with seasonal changes and water use upstream. This isn’t a slow geological transition. It’s a modern one.

The ecology section connects directly to that depth loss. The lake’s food chain is simple but fragile. Brine shrimp and brine flies sit at the center of it, and both depend on a very specific balance of salinity and water volume. When water levels drop too far, salinity spikes. If the lake shrinks beyond a certain point, brine shrimp populations collapse. If that happens, everything above them collapses as well—especially the millions of migratory birds that depend on the lake as a critical stopover. The park is clear about this: if the lake dies, the ecosystem doesn’t slowly adapt. It fails.

Mining and human use come next, and again, depth is the underlying issue. Mineral extraction has always relied on evaporation and concentration, which only works within certain water ranges. As inflows decline, competition for what water remains increases—agriculture, cities, industry, and the lake itself all pulling from the same limited supply. The visitor center doesn’t frame this as a future problem. It frames it as a current one.

The final section on recreation and the shoreline pavilions ties everything together. Over the years, large pavilion structures were built to capitalize on the lake as a destination. These were substantial buildings, meant to host crowds and events, not temporary shelters. Every version failed. Shorelines shifted. Water levels dropped. Fires and storms finished what instability started. Those buildings didn’t disappear by accident—they disappeared because the lake itself kept changing underneath them. Standing outside in the wind, looking across water that is sometimes only a few feet deep, the contrast becomes unavoidable. A lake that was once hundreds of feet deep now survives on the margin, and nearly everything connected to it depends on whether that margin holds. There is a discusting smell wafting in the wind from all the brine scrimp that die.

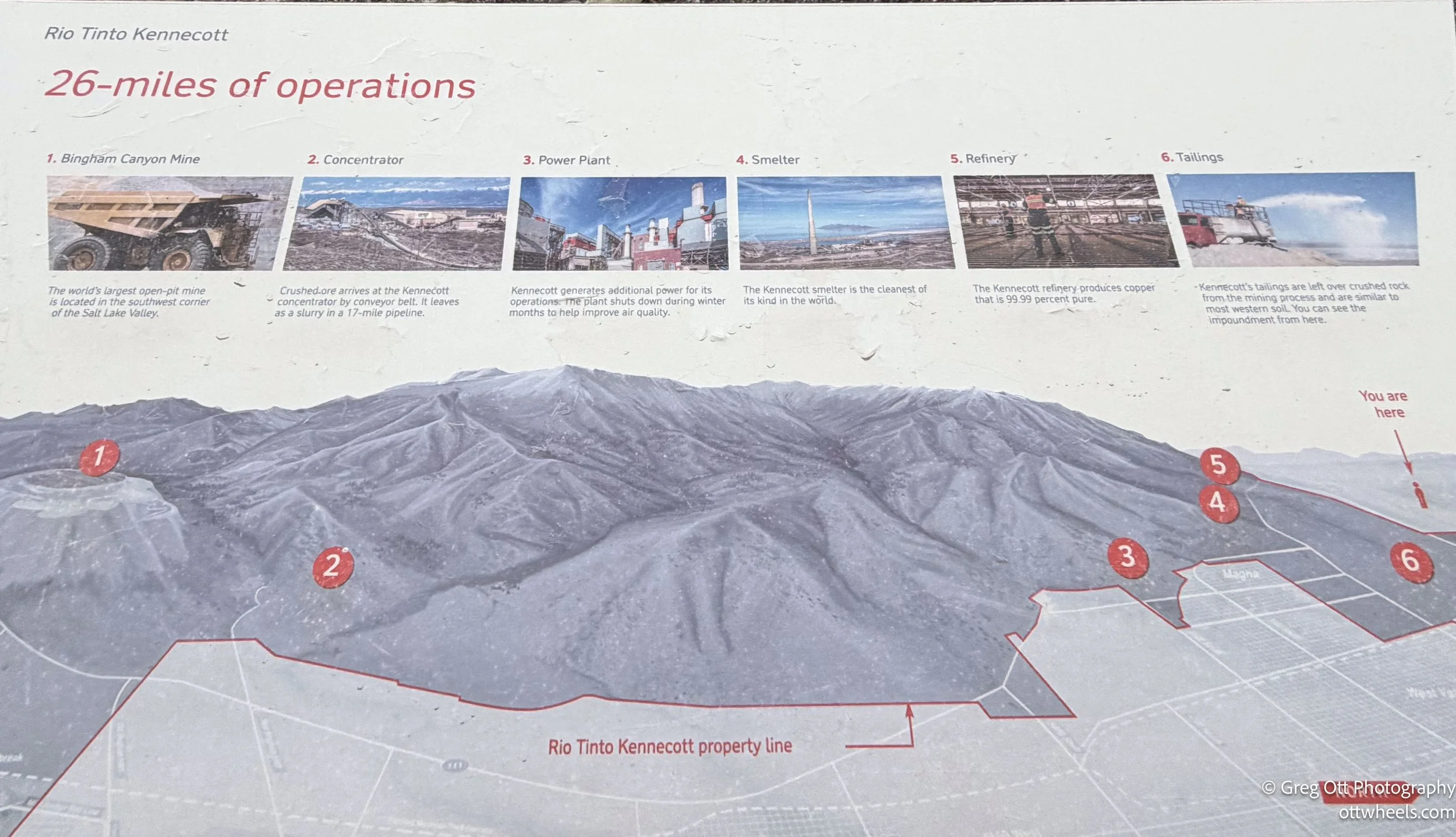

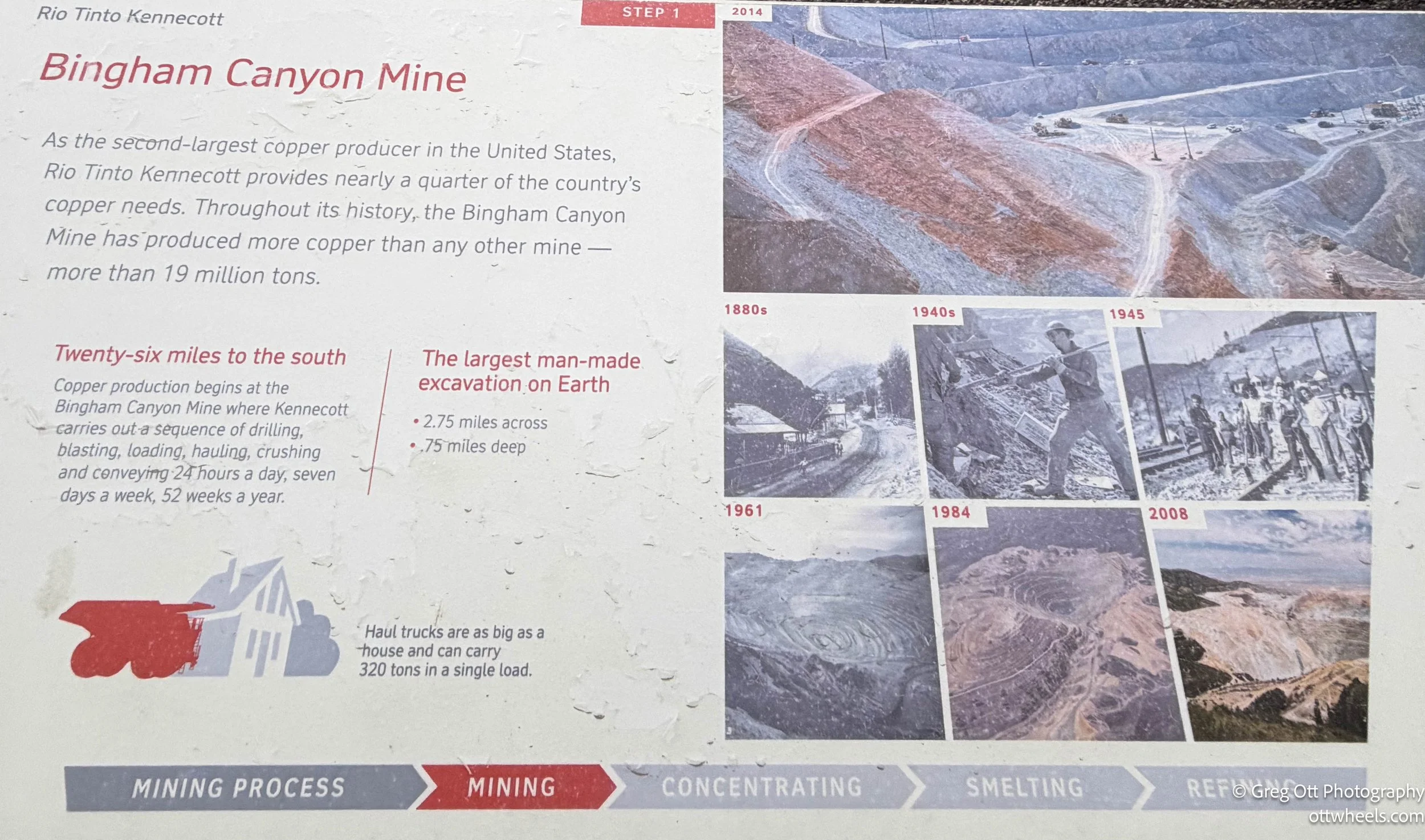

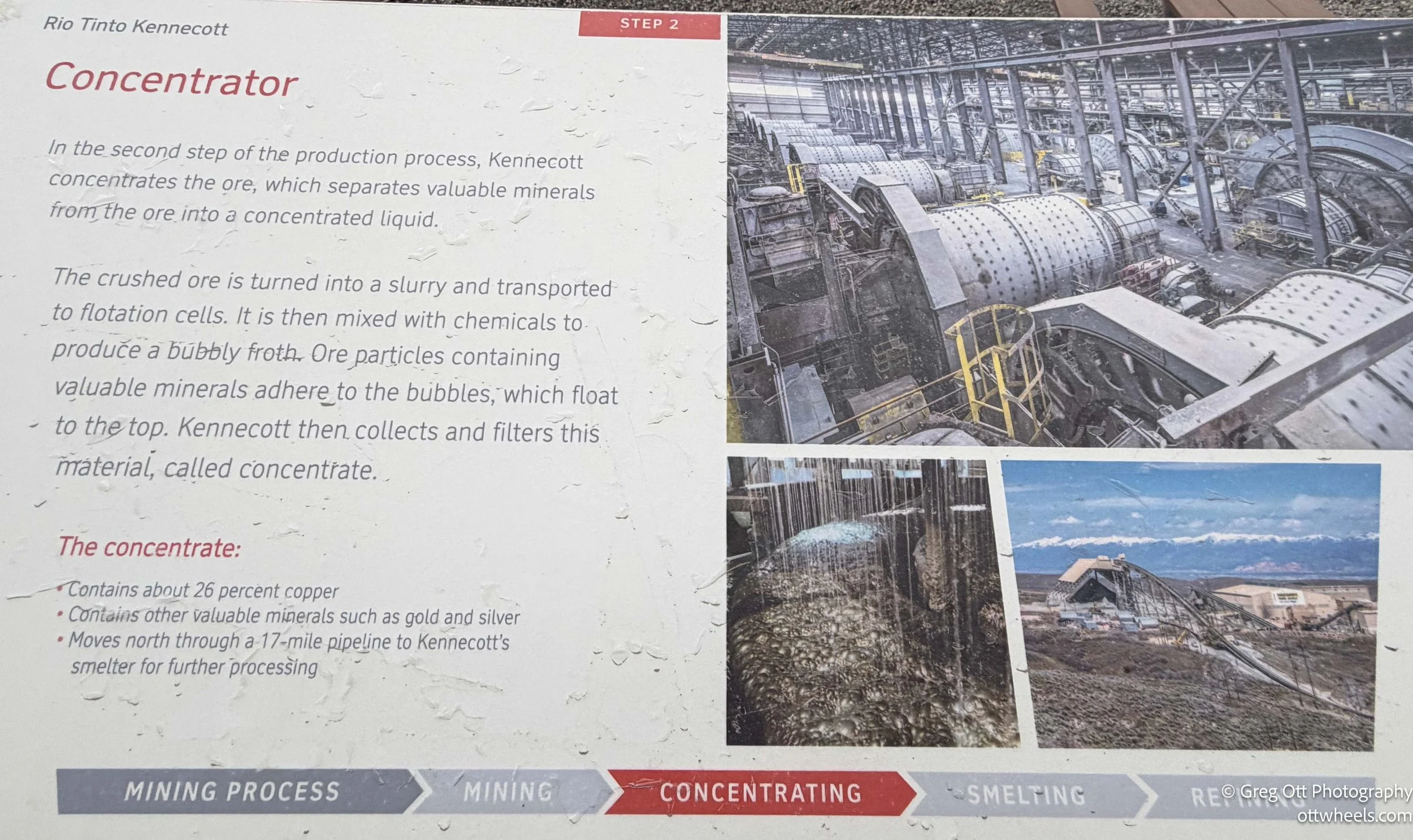

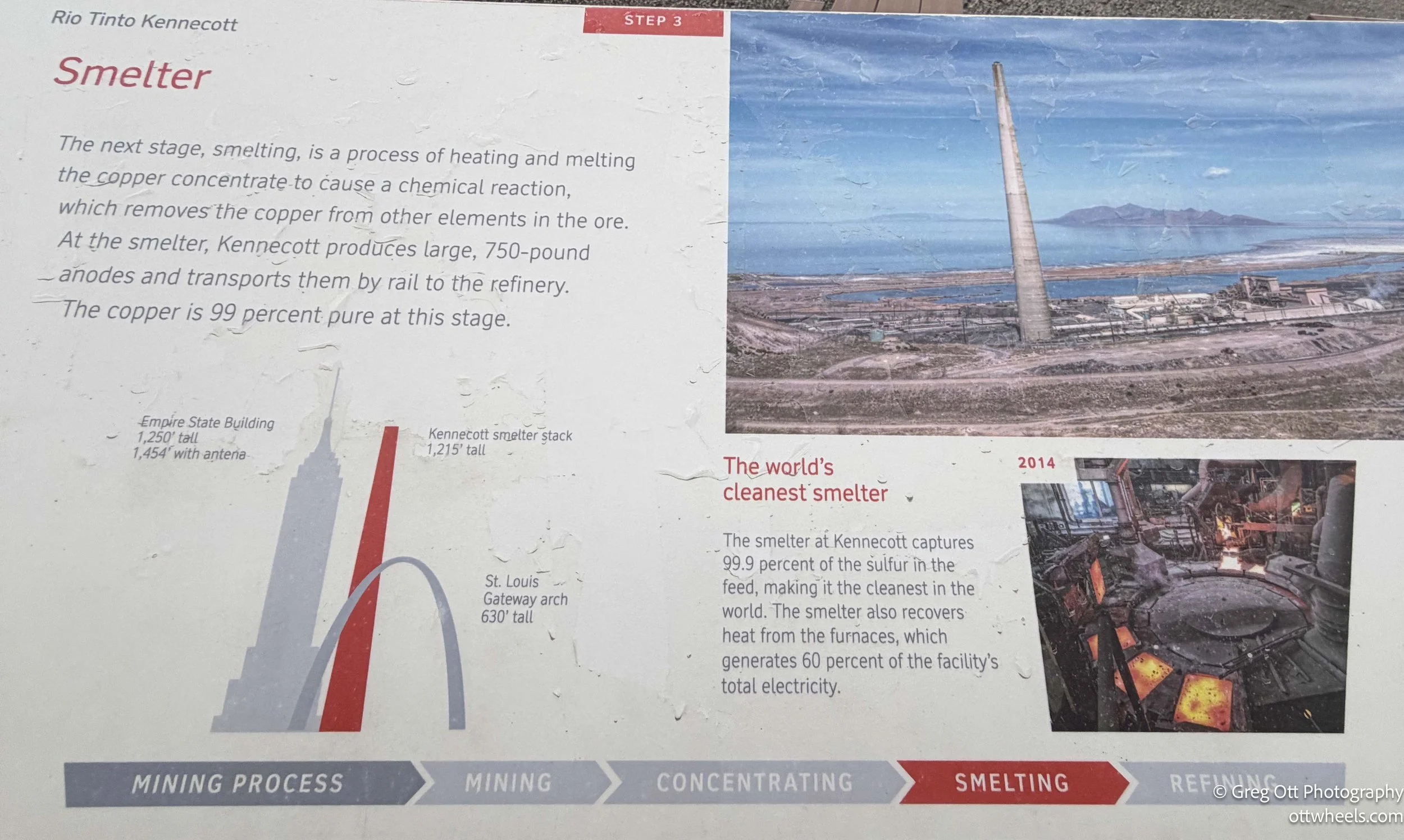

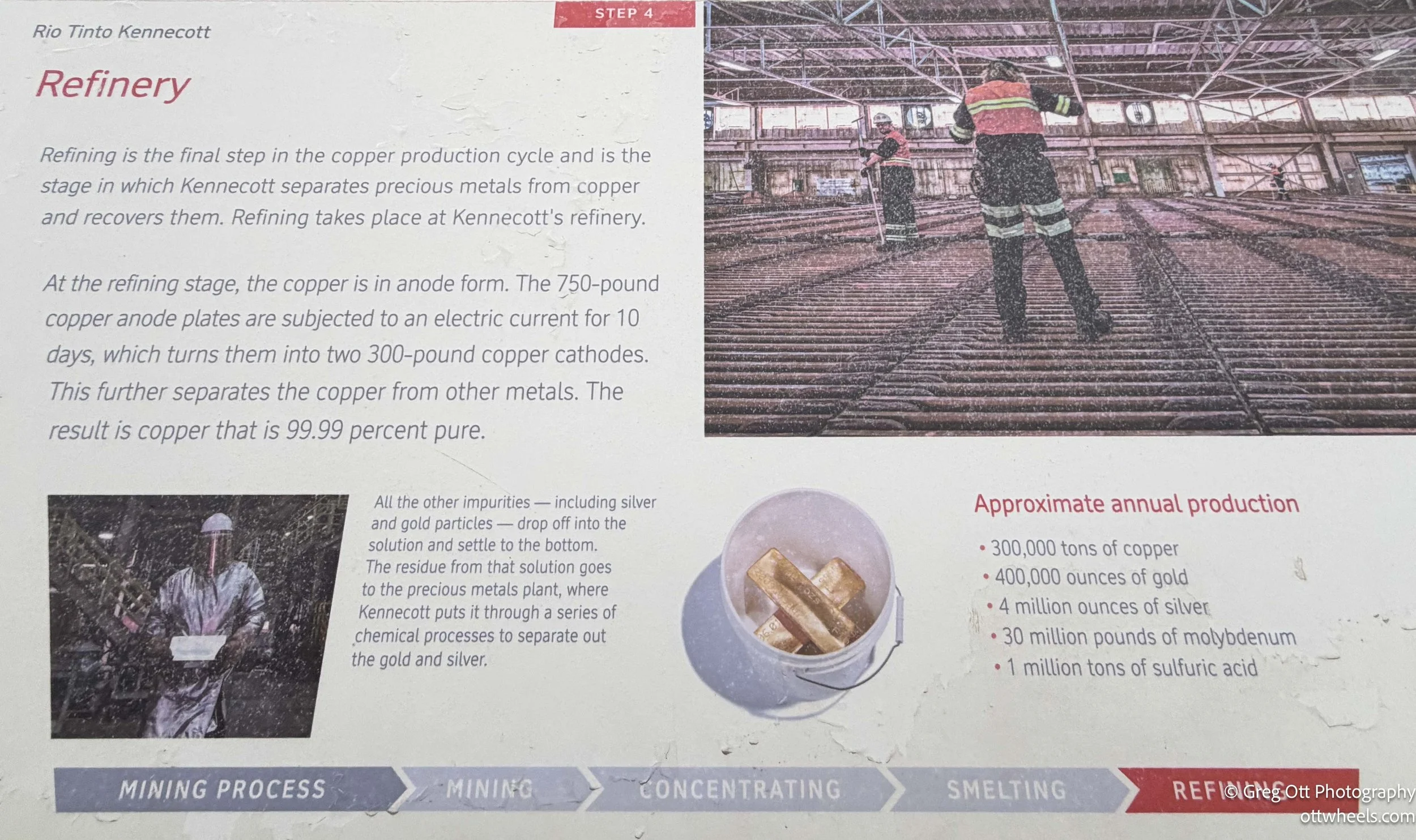

Bingham Canyon Copper Mine

Across the road is the massive Bingham Canyon copper mine. There are plaques explaining its scale and history, which adds another layer to the story of the lake—industry sitting right alongside a stressed natural system. I spent about three hours total, then went outside to take photos. The mine is the worlds largest man-made excavation on earth at 2.75 miles across and .75 miles deep.

I had planned to stay the night at the park, but the wind made that decision easier for me. It was blowing hard, and sand was moving through the air steadily enough that camping didn’t seem appealing. I packed up and headed out.

I stopped at Walmart to top off groceries, then started looking for a place to park for the night. Most of the Walmarts in the greater Salt Lake Area do not allow overnight camping. I ended up in a lot near the state capitol. It wasn’t planned, but it worked nicely.