Martin Guitar Factory & More

I woke at the cracker Barrel in Fogelsville, PA. It was unexpectedly quiet. I drove to a Starbucks nearby and had my bagel, with coffee while I planned out the day. There were things to see around Allentown, but most of them were closed on Tuesday. The Martin Guitar Factory in Nazareth was open and in the opposite direction from where I’m headed, but this looked very interesting.

Martin Guitar Factory Tour

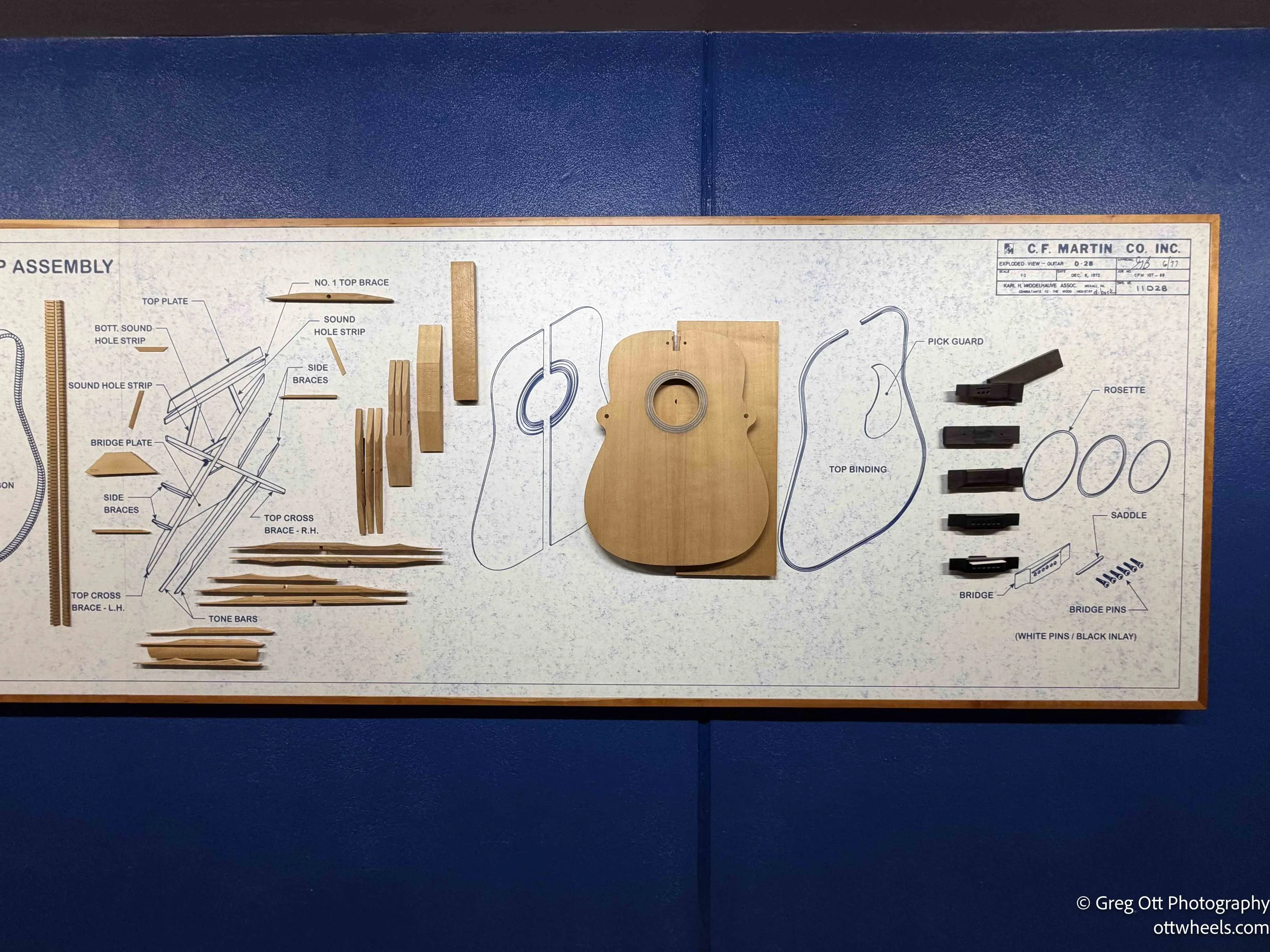

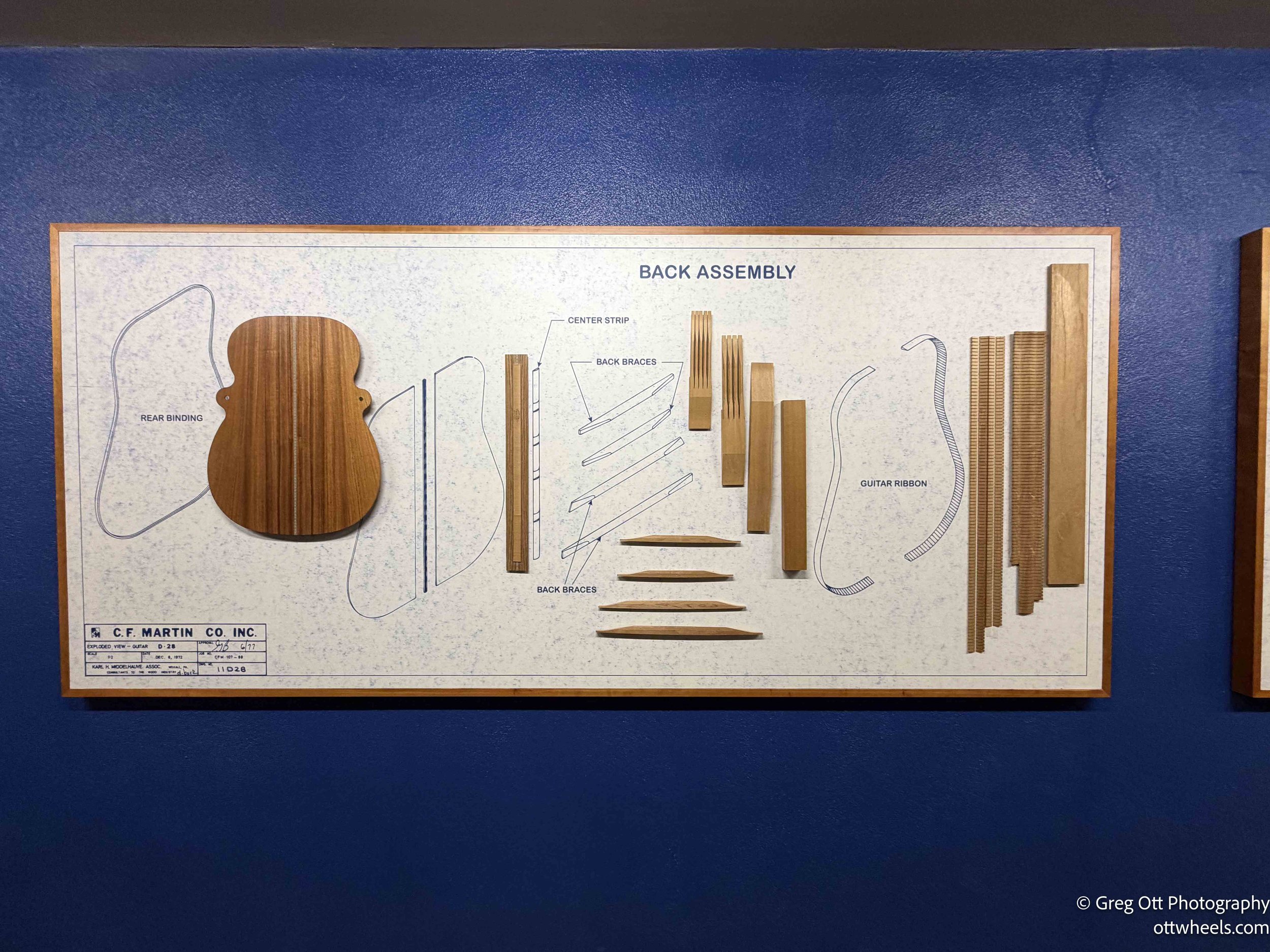

The Martin Guitar Factory tour moves fast — less than an hour — but it gives you a surprising amount to take in. It starts with a simple overview of the main guitar parts: the top, back, sides, braces, neck, fretboard, and bridge. Even if you already know the basic anatomy of an acoustic guitar, it’s interesting to hear how each piece shapes tone, resonance, and durability. It sets the stage for everything you’re about to see in the workrooms.

From there you step into the wood-processing area, which is where the contrast between technology and craftsmanship becomes obvious. One room is filled with lasers and CNC machines cutting pieces with perfect repeatability. The next room shifts to an entirely different energy: individual craftspeople shaping and sanding wood by hand. I was surprised to hear that nearly all leftover wood is collected and recycled, though no one seemed entirely sure what it gets turned into. Still, it’s clear they do their best to waste nothing.

As the tour moves forward, the guide explains the cuts made in the body for ribbing and structural support. I hadn’t realized how many types of internal cuts they use — each one designed to strengthen specific areas without weighing down the soundboard. The conversation then shifted to inlays, which was more intricate than I expected. Depending on the pattern, they may need to make several precise cuts so the pieces fit perfectly. Some of the designs looked impossibly delicate, and all of it requires almost surgical accuracy.

Inside the assembled front and back pieces, you also see how much the internal supports matter. These braces come in different shapes, sizes, and patterns — scalloped, straight, forward-shifted, and more. I knew bracing mattered, but I didn’t realize how much variation there was until I saw it up close. Each pattern changes how the top vibrates, how the bass and treble balance, and how much volume the guitar can produce. It’s the kind of detail you never see when you pick up a finished guitar, yet it defines the entire character of the instrument.

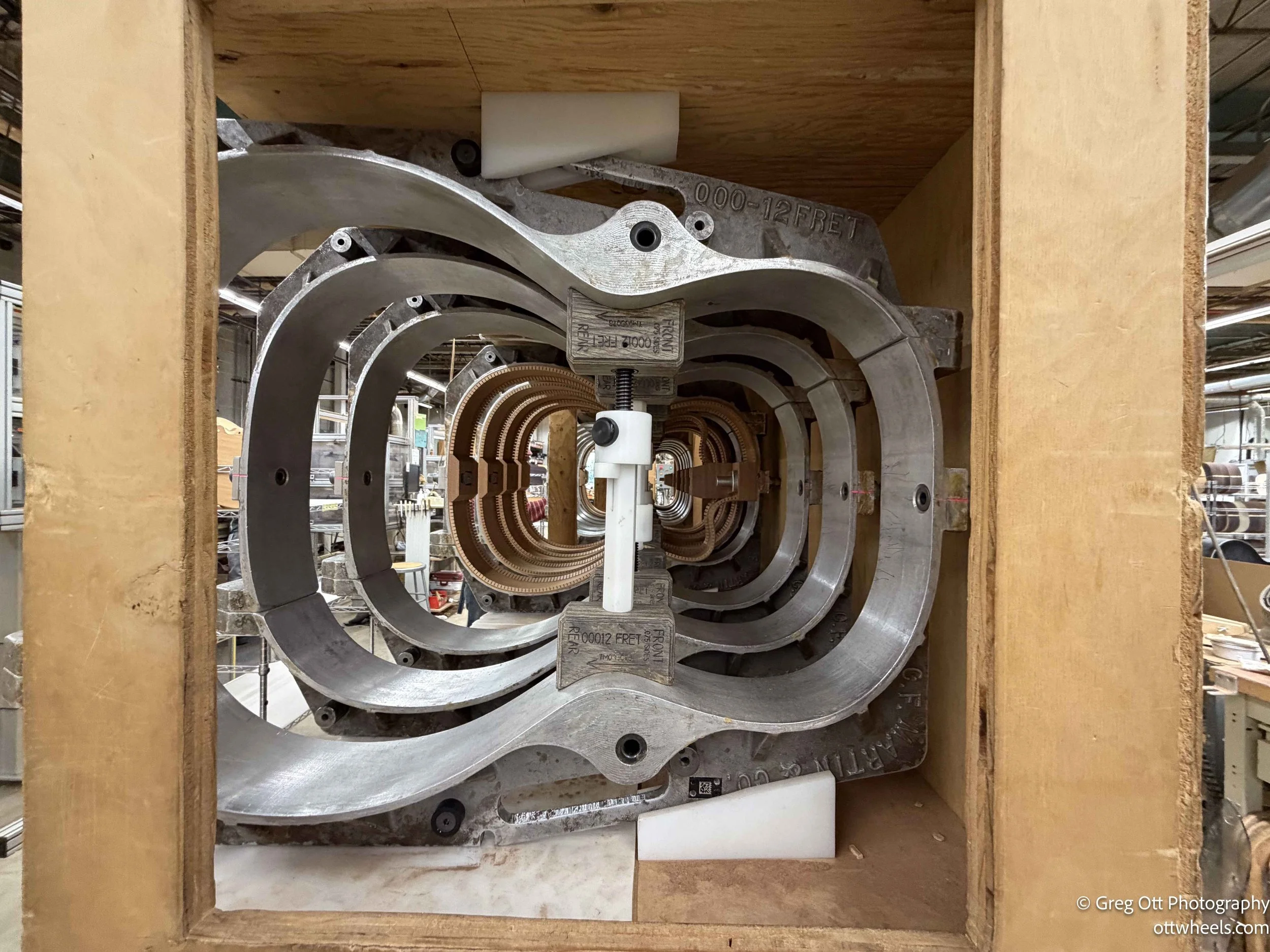

As you walk farther into the factory, you see bodies coming together in different stages — sides being bent, tops glued on, braces clamped, backs lined up. Even with the scale they’re operating at, the process still feels surprisingly personal. Martin builds somewhere around seventy thousand to one hundred thousand guitars per year, depending on demand, but the factory doesn’t feel like a cold production line. It feels more like a series of workstations where each craftsperson handles one repeatable, very specific stage.

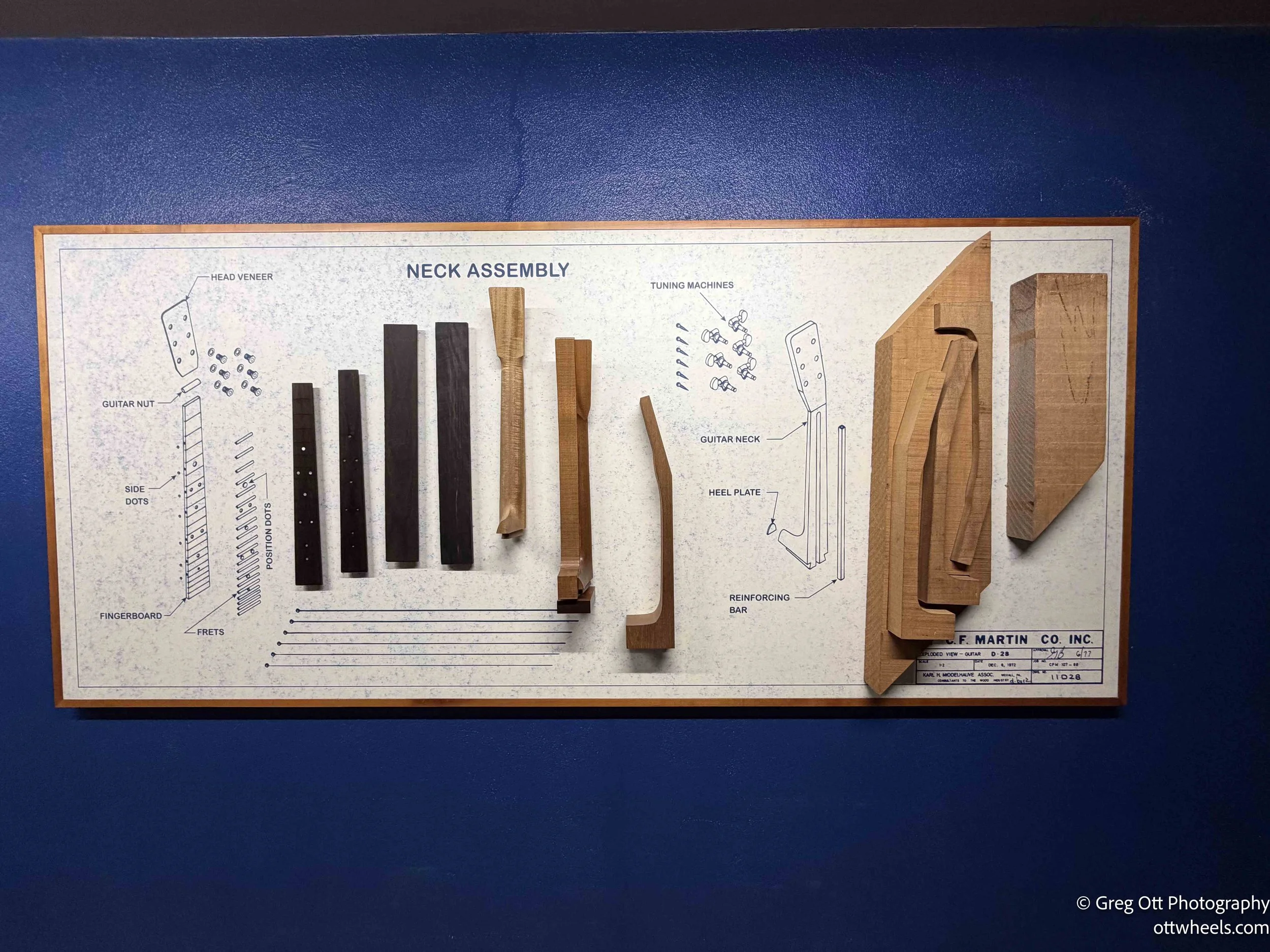

The neck and fretboard areas give you another look at that mix of precision and touch. You watch people file, shape, and smooth the fretboards while machines handle some of the rough shaping work. The guide walked us through a few steps of how they slot the fretboard and prepare it for frets, and you realize how many small measurements have to be perfect for the guitar to play well later. A fraction of a millimeter matters here.

For me, the highlight of the entire tour was watching the frets being installed. It’s done entirely by hand — one slot at a time — and there’s a rhythm to it that almost looks meditative. The tech taps the fret in, checks the seating, runs a finger along the edge, makes a small adjustment, and moves on to the next one. It’s such a simple motion, but it carries decades of experience. The tour wraps quickly after this, but it’s the moment that sticks: even in a factory that produces tens of thousands of instruments a year, each guitar still carries the unmistakable touch of the person who built it.

At the end of the tour, they handed each of us a small round piece of wood that had been cut from an actual soundboard. It was laser-etched with Martin Guitar details, and even though it’s just an offcut, it’s surprisingly lightweight and resonant when you tap it. After watching the whole process, it felt like a fitting little reminder of how much care goes into choosing and shaping the materials long before a guitar becomes an instrument.

The tour exits into the merch area, which is less “gift shop” and more like a compact but serious music store. There’s plenty of memorabilia, shirts, and accessories, but the guitars hanging on the walls pull you in immediately. People were actually trying them out, and one woman in particular was deep into testing twelve-string models. The salesperson helping her clearly knew the inventory well. He kept disappearing into the factory and returning with different guitars for her to try, each with its own combination of woods and features. It wasn’t a sales pitch — it was someone guiding her through possibilities.

What struck me most in that room was how naturally the retail staff moved between the public space and the production area. You don’t often see that kind of fluid connection between a factory floor and a showroom. It made the whole place feel cohesive — as if the same care that goes into building the guitars extends to helping someone find the right one. You could tell they took pride not only in the craftsmanship but in matching people with instruments that fit their style and touch.

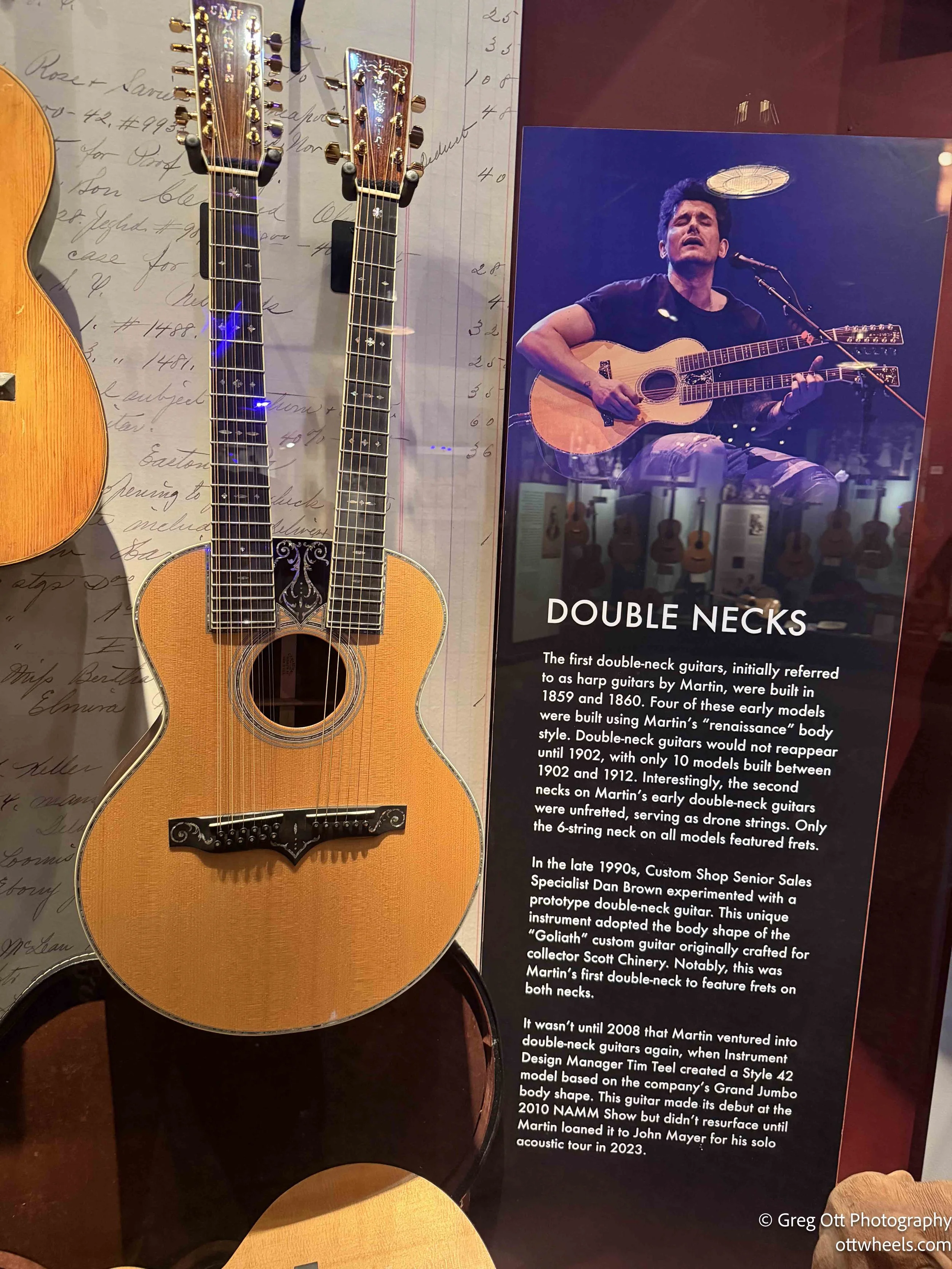

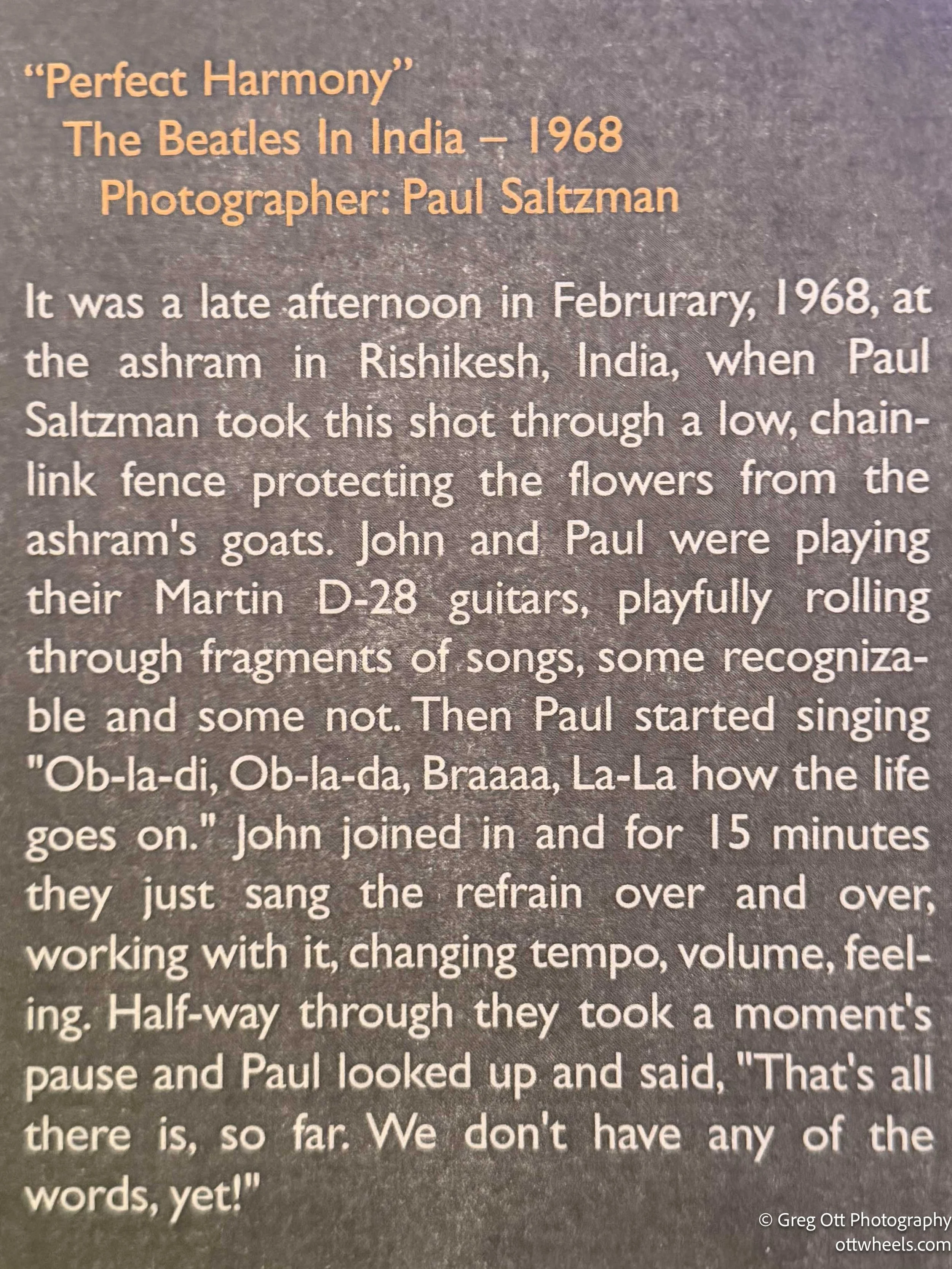

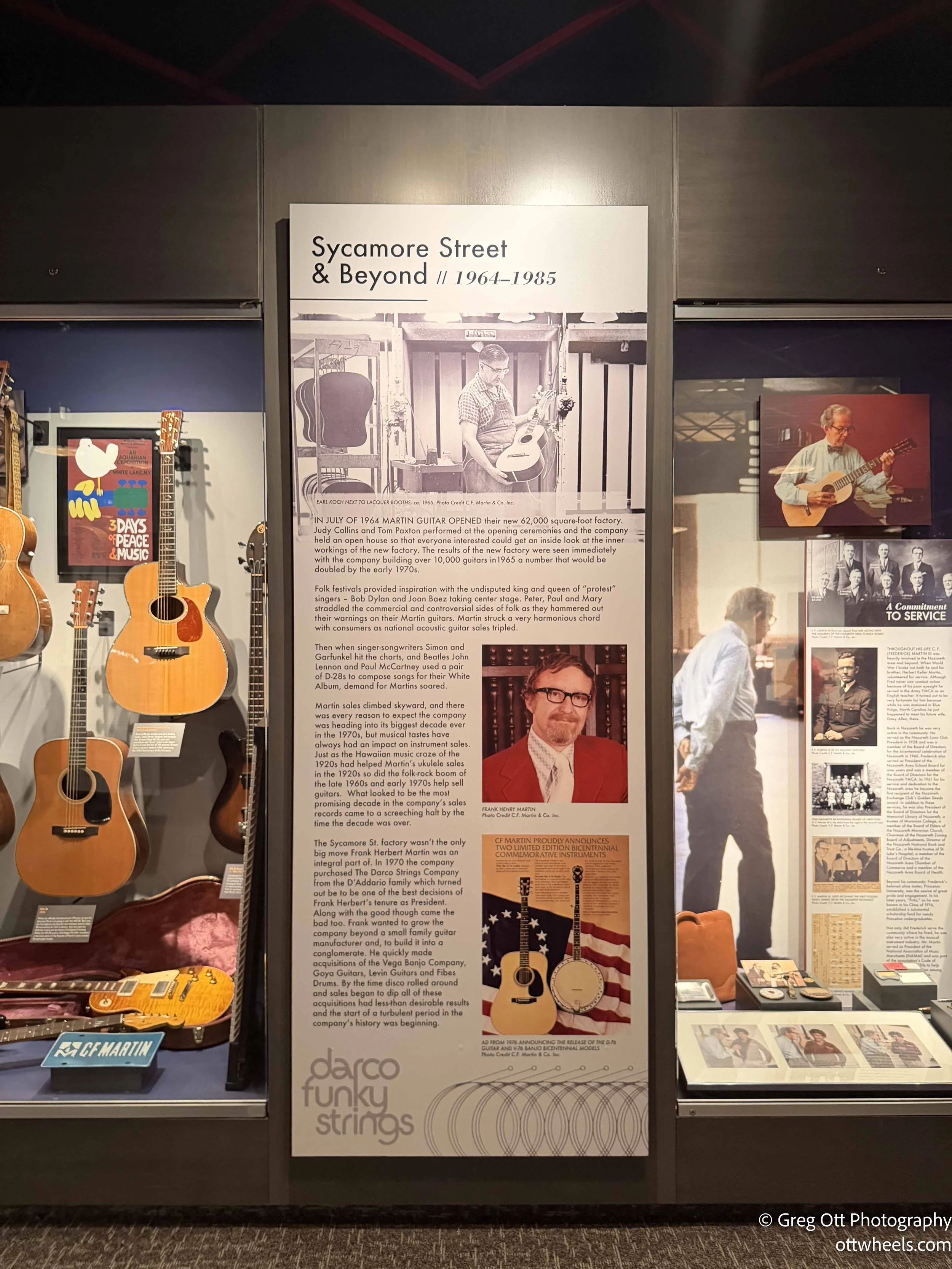

The museum is the quieter finish to everything. It traces Martin’s history all the way back to the 1830s, when Christian Frederick Martin began building guitars in New York before relocating to Nazareth. The earliest instruments look like artifacts from a different world: smaller bodies, simpler ornamentation, and design choices that feel closer to fine cabinetry than to modern guitar construction. As you walk through the decades, the evolution becomes obvious — new body shapes, more elaborate inlays, different bracing ideas, and eventually the introduction of the dreadnought that reshaped acoustic music. There are rare pieces, celebrity-owned instruments, prototypes, and experiments that never went into full production. It’s a surprisingly rich collection for a small space, and it gives context to everything you just watched being built on the factory floor.

Trexler Nature Preserve

After touring the Martin Guitar Factory, I drove over to Trexler Nature Preserve and picked the Covered Bridge hike on AllTrails. I quickly realized I should have brought my crampons. The trail dropped down a steep hill toward the river, and the entire slope was glazed with ice. Every step required some sort of negotiation, shifting my weight to keep from sliding. At the bottom, I crossed a narrow metal bridge and felt the temperature more fully — twenty-eight degrees Fahrenheit, crisp enough to wake me up but comfortable for walking. The cold air actually felt good after being inside the factory, and it set the tone for the rest of the hike.

From the riverbank, the trail followed the water upstream to the covered bridge. Even with the icy footing, it was a beautiful stretch. The creek ran quietly beside me, and the trees framed the bridge in a way that made it easy to stop for photos. Crossing the bridge was like stepping into a postcard version of Pennsylvania: weathered beams, soft winter light, the sound of the creek below. On the far side, the trail continued along the river, but this side was noticeably colder. The sun never seemed to reach it, and the ice was thicker and more unpredictable. Walking was slower, and I found myself analyzing every few feet of terrain just to stay upright.

The climb back up the hill was just as challenging as the descent. Halfway up, I stopped to catch my breath and noticed a small spider making its way across the snow. It was a strange sight — a tiny creature navigating a frozen world much larger than itself. It paused, explored, adjusted to obstacles, and kept going despite what looked like terrible eyesight. Watching it for a few minutes was oddly grounding. Everything around me was slick, cold, and quiet, yet here was this little spider going about its business as if winter were merely another surface to cross.

At the top of the hill, I finished the loop at the preserve’s overlook center. The building had a row of offices on one side, restrooms in the middle, and a large meeting room on the other end. A display inside described a massive set of elk antlers that had come from the preserve — thirty pounds, which seems unreal until you see the photo. The plaque explained that elk antlers can grow as much as one inch per day during peak season, and that the animals shed them every year before growing new ones. After hiking through the cold and feeling the landscape’s steepness firsthand, learning about that kind of biological effort made the place feel even more alive.

Cabella’s Parking Lot

After the hike, I searched for a place to stay nearby but nothing in the immediate area looked appealing, so I checked AllStays and saw several comments praising the Cabela’s in Hamburg as a solid overnight spot. That turned out to be true. The parking lot was enormous, with clearly marked sections separating trucks from RVs and vans. Trucks were routed to the right, and RVs to the left, which was a relief — no loud generators running all night. When I pulled in, there was only one other camper van tucked into the RV section, leaving plenty of space and a surprisingly quiet place to settle in.