Capitol Reef National Park and Butch Cassidy

The campground at Capitol Reef National Park was quiet. I made breakfast and spent a few hours writing, processing photographs, and catching up on online tasks. By 11:00 a.m., I was back in the driver’s seat. I was heading toward Las Vegas for New Year’s Eve, with a stop in Hurricane, Utah, and about a four-hour drive ahead of me.

Fruita

I didn’t make it very far down the road. I stopped to read about the Fruita orchard and wandered among the trees near the campground. Fruita sits at the historic heart of Capitol Reef National Park, and the orchards are not decorative add-ons—they are the reason this place exists at all. Mormon settlers, led by Nels Johnson, established the small farming community of Fruita in the 1880s, planting fruit trees along the Fremont River as a way to survive in an otherwise unforgiving desert. Apples, pears, peaches, apricots, cherries, and plums took hold here, supported by irrigation and the protection of the canyon walls. The layout still feels purposeful rather than picturesque, because it was built to feed families, not visitors.

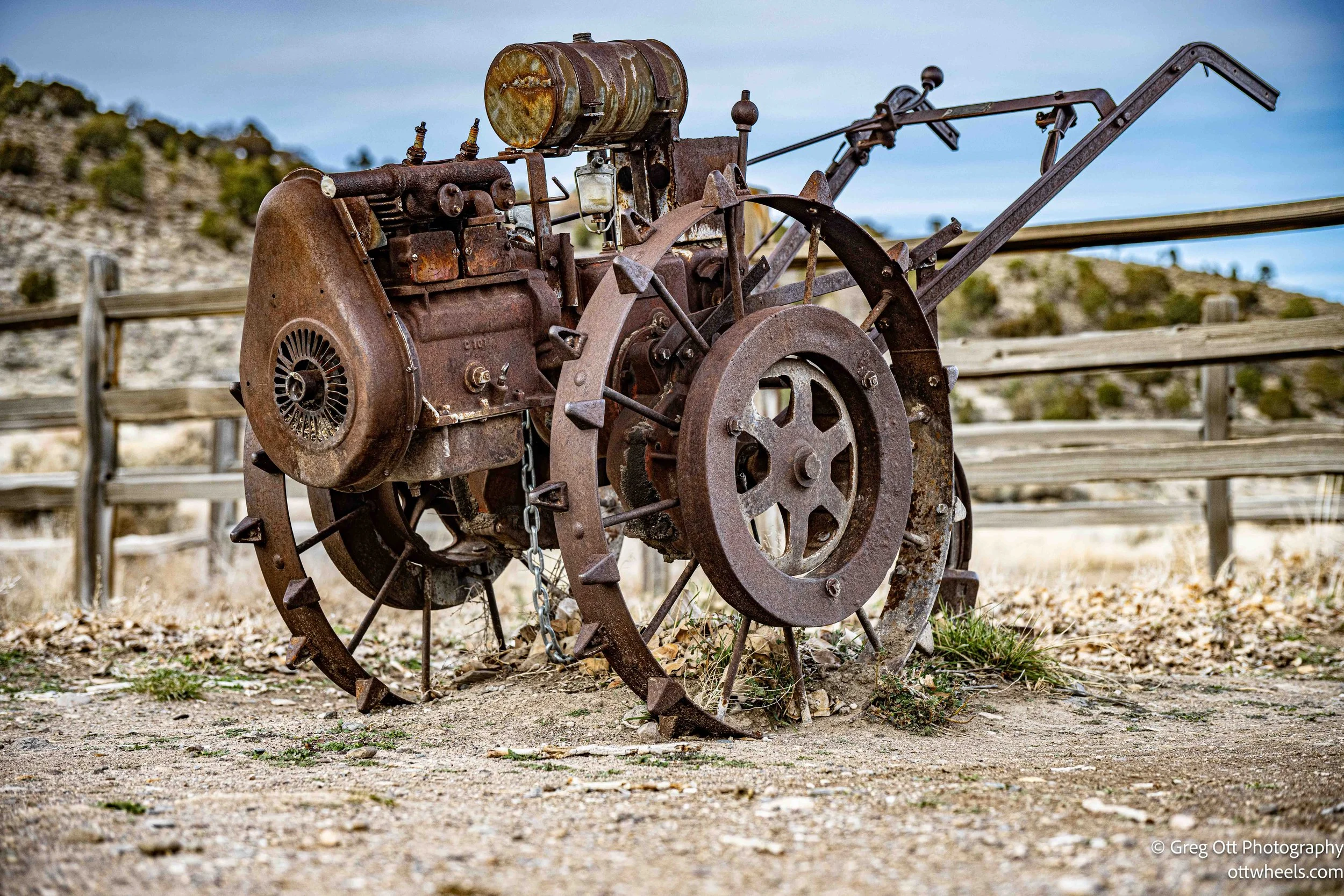

The trees that stopped me longest weren’t inside the fenced orchard at all. They stood nearby—massive Fremont cottonwoods known as the Silent Sentinels. Their trunks were enormous, the bark curled and deeply textured, showing the kind of age that’s impossible to miss. Across the road, a barn held original tools and an old tractor, grounding the scene in the work that once defined this place. Today, the National Park Service maintains the orchards as a living part of Fruita’s history, even allowing visitors to pick fruit in season. I made photographs of the cottonwoods and the orchard surroundings, the air crisp, the sky a deep blue, the polarizing filter cutting through the glare—quiet moments at the edge of a working past that’s still very much present.

Petroglyphs

Not far down the road, I stopped to see a set of petroglyphs carved into the side of a massive rock face. The site is surrounded by grasses and trees, giving it a quiet, grounded feel. A long walkway leads in, clearly designed to provide access while keeping people off the rock itself. It’s a simple solution, and it works—letting you get close enough to study the markings without turning the place into something fragile or overused.

The petroglyph panels in Capitol Reef National Park are among the most accessible in Utah, etched into dark desert varnish along the cliffs beside the Fremont River. Most were created by the Fremont culture, who lived in this region roughly from 300 to 1300 CE. The figures are pecked rather than painted—human forms with trapezoidal bodies, bighorn sheep, spirals, and abstract shapes—cut directly into the rock face. These were not decorations in the modern sense, but marks left by people moving through, living in, and understanding this landscape long before roads or orchards existed.

What struck me most was how matter-of-fact the petroglyphs feel. There’s no signage trying to over-interpret them, and much of their meaning remains unknown. Archaeologists can place them in time and culture, but not intention—whether they marked territory, recorded stories, or held spiritual significance. Standing there, it felt less like viewing an exhibit and more like encountering a quiet record of presence. The panels sit right alongside the modern road, yet they belong entirely to another era, reminding you that this corridor has always been a place of movement, attention, and memory.

Butch Cassidy

I headed out, knowing there was much more to this park than what I had taken in. I stopped for gas and then started the long drive north. About 110 minutes in, a sign near Circleville, Utah, pointed to Butch Cassidy’s Childhood Home along Route 89. I pulled over for a break and a few photographs. The site is quiet and modest, set back from the road, easy to miss if you weren’t looking for it. The cabin itself is a small log house with simple furnishings—spare, functional, and plainly built. Standing inside, it’s clear this wasn’t a place of comfort or excess. He didn’t come from much, and nothing about the house tries to romanticize that.

Butch Cassidy was born Robert LeRoy Parker in 1866 and grew up in a poor, large Mormon family. He would later become one of the most famous outlaws of the American West, known for leading the Wild Bunch gang and robbing banks and trains across Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, and beyond. The plaques at the site lay out his story plainly—his early life, his turn toward crime, multiple arrests, and the mythology that followed him. Cassidy was often described as polite, nonviolent when possible, and almost charming, traits that helped fuel his legend. His death remains uncertain, officially tied to a shootout with Bolivian authorities in 1908, though rumors of his survival persisted for decades. Standing in that small cabin, the gap between the legend and the reality feels wide. It’s a reminder that the stories we tell about the West often start in places like this—simple, hard, and far removed from the fame that came later.

By now it was 3:30 p.m., and I needed to be in Hurricane by 6:00. I wanted to stop and make a few more photographs along the way, but this time I kept driving. The mountains were catching some late color, and I knew I was letting a decent sunset go by, but the day had already been full. I made it to my sister’s house in time for dinner. She’s a good cook, and the meal didn’t disappoint. We opened a bottle of Hess—one of my favorites—and settled into an easy evening.

I planned to leave early the next morning to secure a New Years Eve spot in Las Vegas, so the night stayed unhurried and simple. After a long stretch of road, it felt good to stop moving, sit at a table, and just be present for a while before the next leg of this journey.