Journey to the Northwest Angle

I drove the 20 minutes from my campsite to the buoy that marks the so-called northernmost point in the contiguous 48 states. It’s not actually the furthest north—you’d have to paddle across Lake of the Woods or hike into the wilderness to reach that spot—but it’s the place where tourists come to prove they made it to the top of the map. My Harvest Host host had hinted as much, but standing there with the big blue-and-yellow marker, it still felt worth the trip.

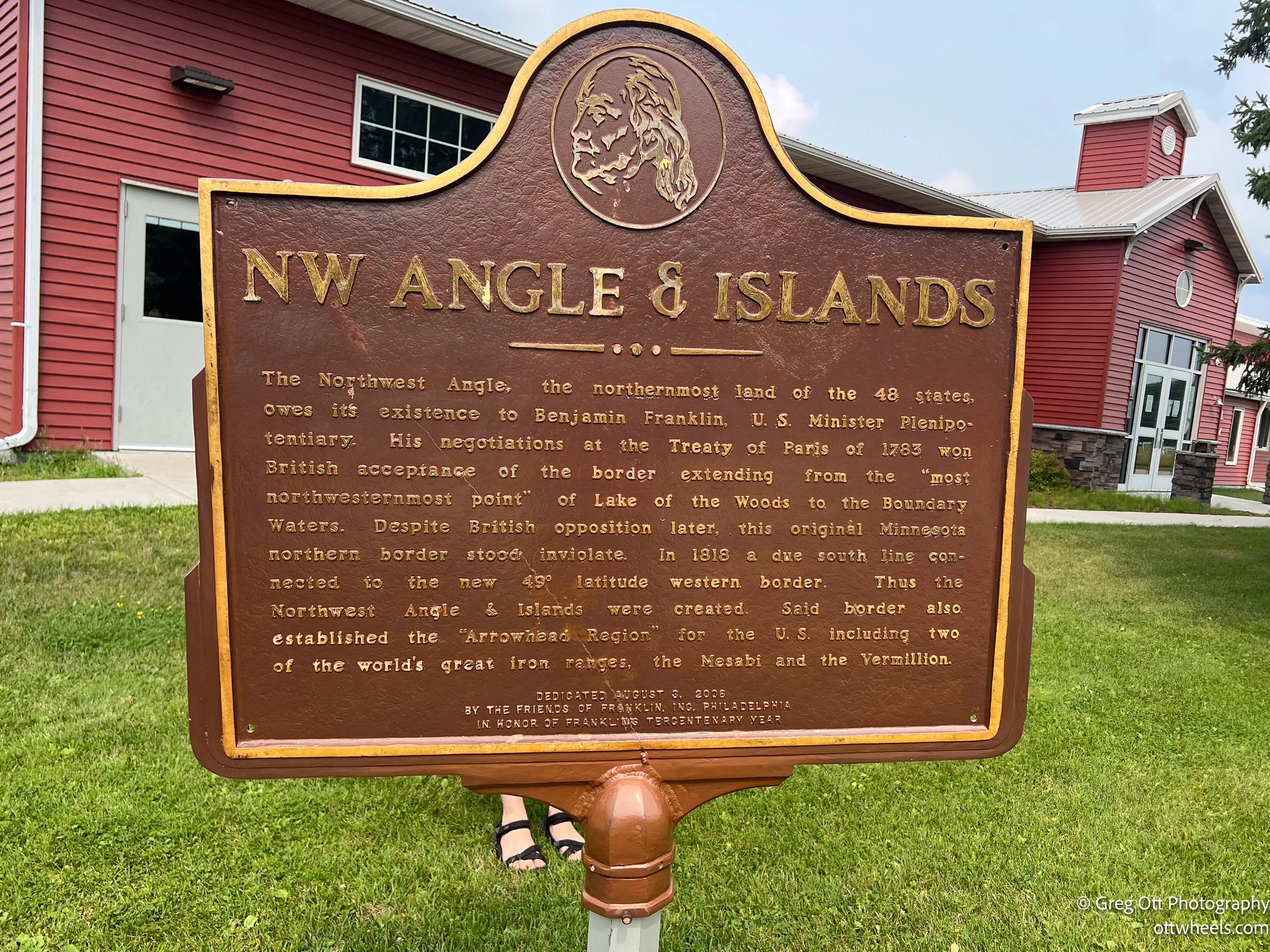

From the buoy, it’s hard not to wonder how this odd little finger of Minnesota—known as the Northwest Angle—ended up jutting into Canada. The story begins in the late 1700s, when Benjamin Franklin was helping negotiate the Treaty of Paris to end the Revolutionary War. The goal was to set a clear border between the new United States and British Canada, and both sides leaned heavily on what was then considered the gold standard of cartography: the 1755 Mitchell Map. According to that map, the Mississippi River’s headwaters lay far to the north, near Lake of the Woods. Franklin, ever strategic, argued for keeping those supposed headwaters in U.S. hands, believing the area would be valuable for trade and future expansion. The British agreed, and the border was drawn in a way that matched their maps—maps that, as it turned out, were wrong.

In truth, the Mississippi begins more than 100 miles south at Lake Itasca—where I’m headed next. Once explorers proved the mistake, the U.S. already had title to the land north of the 49th parallel by treaty. Britain wasn’t happy, but by the time the Convention of 1818 straightened most of the western border along the 49th parallel, they decided the Northwest Angle wasn’t worth a fight. It was remote, sparsely populated, and held little value compared to the vast territories still in dispute. And so, through a quirk of history and a misplaced river on an old map, this small corner of land became the only place in the contiguous United States you can’t reach by road without first crossing into another country.

The Northwest Angle might be a mapmaker’s mistake, but it’s a beautiful one. Getting here means slipping past familiar roads and crossing the border twice, a small adventure before the real one begins. The quiet bays stretch out like mirrors, the tree lines seem endless, and the air—hazy with drifting smoke—softens the edges of everything you see. It’s not a place that tries to impress with crowds or attractions—its beauty is in the stillness, in the way the light filters through the haze, in the feeling that you’ve stepped into a forgotten corner of the map. History and geography may have met here by accident, but together they left behind a place that feels both remote and perfectly complete.

After the buoy, I stopped at the tiny local post office to mail a card. It’s not the smallest I’ve ever seen—that title still belongs to one in Florida—but it’s definitely small-town charming. It is apparently the furthest northern post office in the 48 contiguous states. From there, I finally found Jim’s Corner, the U.S. Border check-in station—a simple, solitary spot where you call in your arrival before continuing on. I spent another hour just driving the gravel roads, photographing an old airstrip, and checking out a few of the other resorts scattered along the shoreline. They’re the kind of places built for fishermen—cabins tucked into the trees, boat docks out front, and the smell of outboard motors and fish guts lingering in the air.

The Northwest Angle might be a mapmaker’s mistake, but it’s a beautiful one. Getting here means slipping past familiar roads and crossing the border twice, a small adventure before the real one begins. The quiet bays stretch out like mirrors, the tree lines seem endless, and the air—hazy with drifting smoke—softens the edges of everything you see. It’s not a place that tries to impress with crowds or attractions—its beauty is in the stillness, in the way the light filters through the haze, in the feeling that you’ve stepped into a forgotten corner of the map. History and geography may have met here by accident, but together they left behind a place that feels both remote and perfectly complete.