Salt Lake City to the Sun Tunnels

I left my spot in Salt Lake City and headed to the Starbucks I’d been going to all week, rolling in just a few minutes before six a.m. Above the Starbucks sits a power yoga studio, and apparently dawn is when enlightenment is scheduled. The parking lot was absolute bedlam. Cars were flying through like it was a qualifying lap, late arrivals whipping around corners in a desperate hunt for parking spaces that clearly did not exist. People were half-backing into spots, half-staring at their phones, and fully convinced that inner peace was only one aggressive U-turn away. I moved slowly, watching every angle, genuinely concerned I might get taken out by someone sprinting toward mindfulness.

It was chaos with a purpose—a kind of caffeinated spiritual urgency that felt completely out of proportion to stretching in a heated room. By the time I made it inside and placed my order, I was still shaking my head. I mentioned the scene outside to the woman at the counter, and without missing a beat she said, “They’re very committed. To yoga. And to not being late.” Understatement of the year.

I drove west out of the city and passed the copper mine. It was rush hour, but luckily I was heading in the opposite direction. I recognized the road and passed the Great Salt Lake State Park. As I left town, the landscape began to change. The hills and mountains faded away and the road flattened out. To my right were large puddles, which I assumed were parts of the Great Salt Lake that are drying up.

There were signs indicating you should stay on the road. That felt like common sense, but clearly many people ignore it—you could see tire tracks heading off into the distance. I’m not sure what you do if you get stuck. In places, the mud looked six to eight inches deep, with tracks running straight through it.

A light fog covered the road, but visibility was still good. As I drove, I started noticing artwork along the way. People had made designs using upside-down beer bottles pushed into the sand. There were arrows pointing east, geometric shapes, and even what looked like a face. Someone had written “Dan” using large stones pressed into the sand. A few miles later, “Stev,” missing the “e,” did the same. There were a few memorials that I assumed marked motor vehicle accidents, though I wasn’t certain. One clever person made a serpent out of tires, and there were several potted plastic plants scattered around.

Along I-80 west of Salt Lake City, there’s a large cement art installation beside the road. There’s a highway sign warning not to stop. I wanted to pull over, but the fog was thick, there was no easy place to do so, and the warning felt serious. I couldn’t help wondering why the state would allow such an interesting piece of artwork to exist without a safe way to stop and look at it.

I later learned the sculpture, Metaphor: The Tree of Utah, was created by Swedish artist Karl Momen and completed in the late 1980s. It’s made primarily of concrete and colored glass, which is why it looks like a massive cement form rising out of the desert. The bright sections were originally intended to glow when lit from within, though that feature hasn’t worked for years. Apparently, people used to stop on the shoulder to photograph it, which became a safety issue. I read that there may be legal access via nearby frontage roads if you really want to get closer, though I’m not sure how realistic that is. From the highway, it feels like something meant to be seen in passing—an abrupt, surreal landmark in the middle of empty space.

The fog continued to thicken as I got closer to Wendover. My first destination was the Bonneville Salt Flats Speedway. There’s a roadside rest stop about ten miles before the exit heading west. The fog was so dense that I decided to stop rather than push on. The rest area sits directly across from the speedway, I think.

I got out and took a few photos. The light was bright, but the fog was so thick it created strange illusions. Unfortunately, all of the photos were out of focus. I hadn’t had breakfast yet, so I made oatmeal with a lot of toppings and had another cup of coffee while I waited for the fog to lift. I was there for about two hours.

Eventually, I started hearing truck air brakes releasing and figured the fog must be thinning. I got out to verify and there was a black bird perched on the back of a tractor trailer, making all kinds of noise while cleaning his feathers. I stood and watched for a bit and then got back in the van and drove the short distance to Exit 4. The road turns back parallel to I-80, and I could see the rest stop in the distance as I reached the end of the road.

If it weren’t for the sign, Bonneville Salt Flats, I don’t think anyone would know this place is famous for land speed records. All you really see are mountains in the distance and water a few inches deep covering which eventually recedes. I assumed this was the raceway. I had expected to see mile markers like in the movies. Those apparently are not permanent.

I spent some time there taking photos of the landscape and reading the signs and stickers on the back of them. Someone scribbled, “Go home & compile a better operating system.” I smiled and wondered how long that had been there.

The sun had come out and the temperature was in the fifties, so I sat and watched what was happening—which wasn’t much. I sometimes find it interesting to just sit and listen to people visiting places like this. Kids had no perspective of where they were and weren’t impressed, even when their parents explained the history of cars and motorcycles attempting to break speed records right where we were standing.

One couple must have taken a hundred photos of themselves. She directed the whole thing, telling him how and where to pose. He seemed into it as well.

I’m not sure exactly when I left the salt flats. I stopped in Wendover for gas since it didn’t look like there were many stations near the Sun Tunnels. The drive up Route 30 was actually very pleasant, mainly because there wasn’t much traffic. There were a few trucks, but everyone seemed content to stick close to the sixty-five-mile-per-hour speed limit.

There aren’t many towns along this route, and when there are, everything looks rundown, windblown, and aging—people included. It seems like a hard life out here. Montello, Nevada, probably the largest town on Route 30, had a population of about fifty in 2018, and that may be generous. It also had a one-room post office.

The Cowboy Bar Café sits right along Route 30. It was decorated with steer horns, skulls, and lanterns hanging from the porch overhang. The banisters were built from logs and scavenged branches, giving it a very distinctive look. According to a sign above the porch, there’s music on Saturday nights. A tattered Trump 2024 flag was also attached above the porch roof. I wasn’t sure what purpose it served, but it was hard to miss.

What should have been a two-hour drive turned into nearly three because of the poor quality of the dirt road leading off Route 30. The last eleven miles were slow going. I finally arrived at the Sun Tunnels around five p.m. The sun was already low over the western mountains, and I was relieved to see there was virtually no mud.

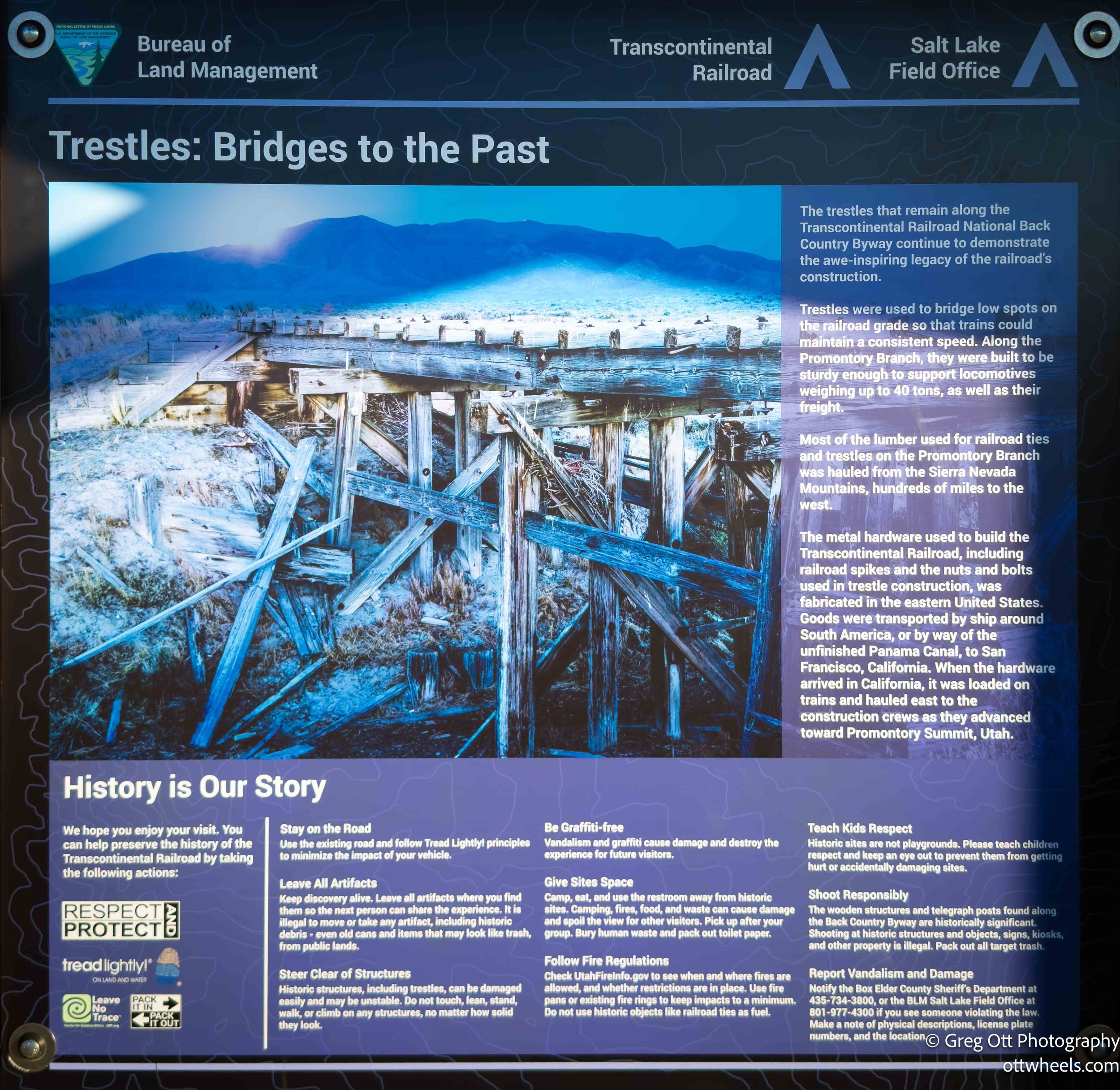

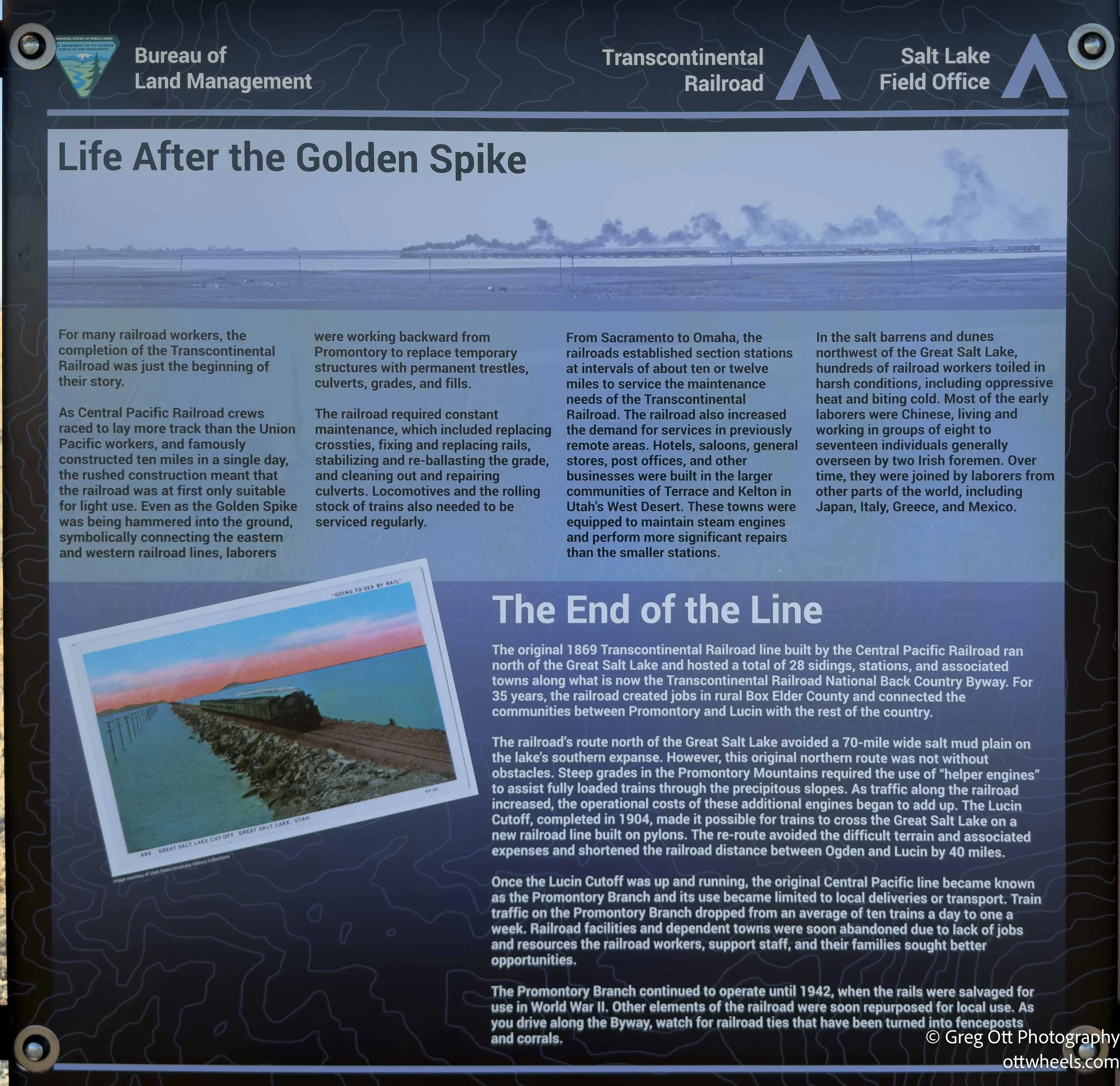

About 7 miles down the road there was a sign for the transcontinental railroad which passed through the valley not far away. I’d be visiting the golden spike location in a few days. I stopped to read the plaques and then continued on.

I passed an “oasis” with a sign filled with bullet holes (Lucin, Utah). I guess there’s not much else to do around here other than shoot at signs. Some people practice shooting the numbers out of distance signs. It looks like they continued to shoot 50 shots at the same place until it was unreadable. Out here, signs matter more than other places because if you haven’t loaded your google map before you got here, there’s no cell coverage often. I didn’t see much water in the two small ponds.

I had read about the Sun Tunnels and found them intriguing long before I came out here. Created by Nancy Holt in the mid-1970s, they sit far out in Utah’s Great Basin desert, intentionally removed from towns, roads, and distractions. As I understand it, Holt designed the work as a precise alignment of four massive concrete cylinders, positioned to frame the sunrise and sunset during the summer and winter solstices. I was the only one there today, though during the solstices many people apparently make the trip. Small perforations drilled into the tunnel walls map specific constellations. I’m not entirely clear on their purpose beyond adding another layer of depth to the work. It’s less about spectacle and more about awareness—standing inside them, you start to notice how the land, the sun, and the stars quietly govern everything around you.

I knew I wanted to do some astrophotography later in the evening, so I tried to get some sleep. I must have had too much caffeine during the day because I couldn’t fully relax. Around midnight, I started taking fifteen-second exposure sequences for star trails. The lights from Salt Lake City in the distance were much brighter in the images than they appeared to the naked eye. Our brains do a good job of convincing us there’s nothing there when, in fact, there is.

I was alone most of the night. Around two a.m., while setting up another shot, I noticed a light moving horizontally along the mountains at about the speed of a bicycle. I didn’t hear a motor. I can’t imagine riding a bike out there at any time, let alone at two in the morning. After about fifteen minutes, the light disappeared.

By four a.m., I had run out of steam. I packed up the camera gear, climbed into bed, set the alarm for noon, and fell asleep almost immediately.