Brighton Ski Resort

It was just an absoluetly fun day of skiing at Brighton. People always make the difference and today was no exception. The day started off slowly at 5:45 a.m. I stopped at starbucks for my morning coffee to help will me up Big Cottonwood Canyon.

It was just an absoluetly fun day of skiing at Brighton. People always make the difference and today was no exception. The day started off slowly at 5:45 a.m. I stopped at starbucks for my morning coffee to help will me up Big Cottonwood Canyon.

Brighton Resort sits at the very end of Big Cottonwood Canyon, and I pulled in around 7 a.m. Staff were already out directing traffic. I was the second vehicle in the lot and, for the second day in a row, ended up parked directly in front of the lift. With two hours to kill before the mountain opened, I made breakfast and eased into the morning.

While my oatmeal cooked, I flipped through a few brochures I had picked up at Great Salt Lake State Park. One, from Utah Stories, was titled Hope for the Lake? It laid out how the crisis facing the Great Salt Lake didn’t arrive all at once but built quietly over decades. Drawing on data from the Environmental Protection Agency, the article pointed to US Magnesium as the source of nearly ninety-two percent of Utah’s toxic air emissions, tied to hazardous waste that was never properly contained. As groundwater levels drop, that waste isn’t staying buried—it’s drying into fine toxic dust that can be carried by wind into communities along the Wasatch Front. The article also noted similar environmental damage connected to the company’s operations in Peru, suggesting a long-standing pattern rather than a local anomaly.

What stayed with me most was how much of this has been hiding in plain sight. When Dr. Moench warns that, without serious legislation in the next ten years, we could be looking at a lake that no longer exists—and that Salt Lake City could become unlivable—it doesn’t sound dramatic. It sounds like a deadline. The real cost seems less about sudden catastrophe and more about the years lost by choosing not to act sooner.

I read a couple of brochures about the Sun Tunnels next and sketched out a four-day plan to head northwest and photograph the installation. Somewhere in the middle of all that, a group of college students pulled up in front of the van, music playing just loud enough to drift inside. The lifts were spinning. That felt like my cue.

The first lift moved quickly and seated six. I rode up with a local who lives at the base of the mountain and was squeezing in a few runs before work. He walked me through the layout of the mountain. I hope he realizes how rare that kind of access really is.

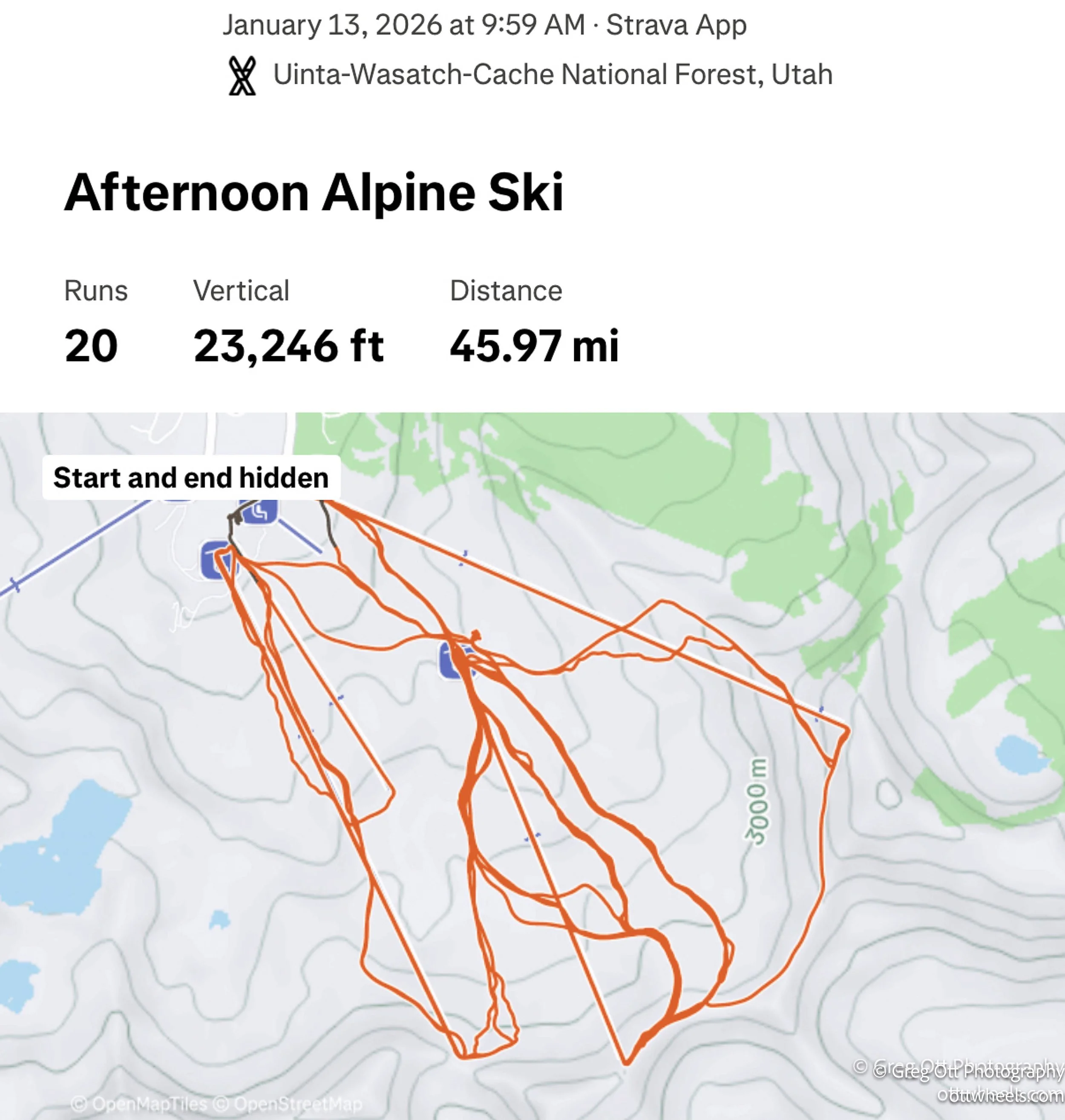

From there, the day settled into a rhythm where everything just worked. The snow was in great shape and well groomed, the sun showed up in the right amounts, and lift lines never felt like a chore. What really stood out was how social the mountain felt. Lift rides turned into easy conversations—with young local students, a couple from West Virginia, a couple from Taiwan, a Chinese couple, and a software engineer who had lived through many of the same hardware and software development cycles I had. It made the day lighter, almost communal.

I stopped for lunch around 12:30 at the on-mountain restaurant. The food was, frankly, rough. Basic burgers, pre-bottled drinks, no french fries, and some deeply disappointing tater tots with a spicy seasoning that didn’t save them. Greasy and heavy. I asked about salad or yogurt and was told they didn’t have any because they were “up the mountain,” which made little sense given that a sister resort nearby manages just fine. I ate inside only because every outdoor table was already taken.

After lunch, I pushed into areas I hadn’t skied yet. A few runs stood out—steep, engaging, and satisfying—but dotted with exposed rocks that demanded attention. I picked careful lines and skipped anything questionable. My skis were happier for it.

. He liked to ski fast, which pushed my pace, bumped up my run count, and added to the vertical.

As the afternoon wore on, the mountain seemed to relax. On one lift, I rode up with a woman in her mid-twenties skiing solo and a Swedish guy named Hans, also skiing alone for the week. Hans and I talked the entire way up—Europe, politics, the general frustration with leadership in the US and Europe, especially when it comes to Ukraine. We were very much aligned. We ended up skiing together for about two hours. He liked to ski fast, which pushed my pace, bumped up my run count, and added to the vertical.

Around 3 p.m., Hans headed back to his hotel, and I stayed out for another forty-five minutes on my own. I kept thinking about my first run a week earlier and how rough I’d felt then. The contrast was hard to miss. Somewhere along the way, the altitude issues had faded and skiing finally felt natural again, like my body had caught up with where my head already was.

At the same time, I couldn’t ignore something else that had been hanging around for weeks. I’d been dealing with a dull chest pain on my right side for about six weeks—something that felt muscular, more noticeable the deeper I breathed. During that last hour on the mountain, it started to feel worse when I took deep breaths. It didn’t stop me from skiing, but it was there, quietly reminding me that even on a really good day, not everything is completely in sync yet.

I finished the day by skiing straight to the bottom, stopping almost directly in front of the van. I packed up, changed into jeans, and took in the scene. The parking lot had turned into complete chaos, so I ducked into the Brighton Lodge for a latté and a very flaky croissant. Inside was a small exhibition on loan from the snowboarding museum—historic boards from key moments in the sport. I didn’t recognize the names, but each board came with context explaining why it mattered. It was a quiet, fitting way to end a really solid day on the mountain.

I stopped at Planet Fitness for a shower and then sank into the massage chair. I set it to an extra-deep cycle and could feel the rollers working their way up and down my back, really digging in. The pressure on my legs and arms was intense but in a good way, the kind that makes you realize how much tension you’d been carrying around. When it finished, my body felt loose and reset, like I’d finally hit a pause button.

From there I headed to Flower Child for dinner—one last stop—before driving back to my spot above the University. It was my final night in Salt Lake City. Earlier that morning I’d decided that the next leg would take me west and north, toward the Sun Tunnels and the Bonneville Salt Flats. The day had wrapped itself up neatly, and the road ahead was already starting to take shape.